The Five Great Technology Surges

- The First Great Surge – The Industrial Revolution Textiles and Canals

- The Second Surge – Steam & Railroads – This Page

- Third Great Surge – Electricity, Heavy Engineering, and Steel

- The Fourth Great Surge – I.C.E. (Internal Combustion Engine) and Oil

- The Current Great Surge – ICT – (Information & Communication Technology) – Microprocessors and Telecoms

- Return to the Great Technology Surges Index – Main Page

The Second Great Technology Cycle – Depression and Revolutions

The Second Innovation Cycle of the Industrial Revolution: Steam & Railroads

Surge Two: Steam & Railroads (1848)

The Railway Revolution

The second technological cycle emerged when industrial expansion outgrew the capacity of canal networks. The Pennine Mountain Range, rather than hindering progress, catalyzed the development of railway systems to transport textiles and coal—products of the first wave’s growth. Early rail lines, strategically placed along economically viable routes, proved remarkably profitable. By late 1844, railway investments yielded dividends four times higher than standard interest rates.

Establishing a railway company required minimal bureaucracy: a committee formation, route survey, and raising merely one-tenth of projected construction costs through scrip (shares). In the absence of formal stock markets, these investment opportunities were advertised in newspapers, creating a dangerous echo chamber of speculation. The press, benefiting from increased advertising revenue, enthusiastically promoted these schemes, further inflating the bubble.

Parliamentary oversight remained inadequate despite the Railway Act of 1844, which established a dedicated examination department. With non-binding recommendations and insufficient resources, the system couldn’t properly evaluate the flood of proposals. Conflicts of interest abounded, as many Members of Parliament personally invested in projects they were tasked with examining.

The Speculative Bubble

Railway speculation escalated dramatically throughout 1845:

- January: 16 new railway schemes

- April: Over 50 proposals

- August: Parliament approved over 100 railway acts, authorizing 3,000 miles of new track

Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel attempted to mitigate risks through the Bank Act of 1844, which restricted the Bank of England’s debt-to-asset ratio. This measure, intended to shield the economy from speculation, proved insufficient.

Northern provinces witnessed even riskier practices. Exchange Banks emerged, offering loans of up to 80% against railway share collateral. None survived the decade. Notable figures like George Hudson, who at one point controlled two-thirds of Britain’s railways, engaged in questionable practices—paying dividends from working capital rather than profits and commingling personal and business investments.

By June 1845, the speculative frenzy had drawn in 20,000 railway investors, including 157 Members of Parliament. Suspicious applications proliferated, with impossible subscriptions like two brothers—sons of a charwoman living on barely a pound weekly—somehow pledging £37,500.

The Collapse

The bubble burst in October 1845. Share values plummeted by 40% within a month. With no bankruptcy laws yet established, Parliament passed the Dissolution Act in May 1846 to address the wave of failing railway companies. The full economic impact took over a year to materialize.

By January 1847, the Bank of England raised interest rates to protect dwindling reserves. The “week of terror” began on October 17, with assets trading at merely 10% of their value and gold reserves reaching critically low levels. The Bank of England required emergency exemption from the Bank Act to avoid insolvency. By 1848, Britain’s economy began stabilizing, while continental Europe faced more severe consequences.

Revolutionary Aftermath

Mike Rapport’s “1848: Year of Revolution” documents the cascading crises across mainland Europe following Britain’s crash. Food prices skyrocketed—bread costs increased by nearly 50% in France—while industrial demand collapsed. Unemployment reached catastrophic levels in manufacturing centers: in Roubaix, 8,000 of 13,000 textile workers lost jobs; in Rouen, people endured 30% wage cuts to avoid unemployment. Vienna alone saw 10,000 workers laid off amid record food prices, with no government assistance programs available.

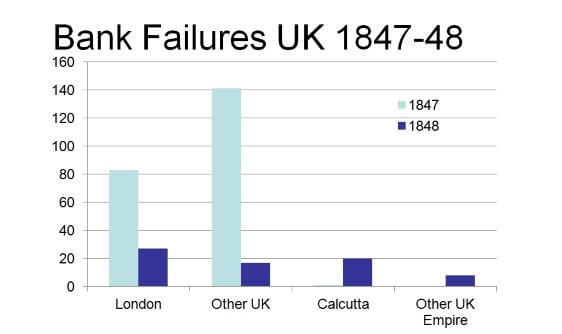

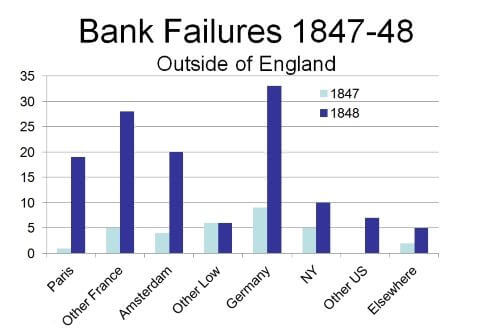

This pattern exemplifies a “technology Great Surge crash.” As Britain’s economy contracted, other European economies suffered more severely due to capital flight. The pattern of bank failures illustrates this spreading crisis (graphs show the carnage and geographies affected):

- 1847: 140 bank failures in London and other UK cities

- 1848: Banking crises peaked in the British Empire’s periphery (India) and mainland Europe (40+ failures in France, 30+ in Germany)

Divergent Outcomes

Britain emerged with Europe’s most advanced railway system despite the speculation. Their earlier regulatory adaptations—the 1844 law requiring third-class passenger accommodation and the 1846 Gauge Act standardizing track widths—created a more resilient infrastructure. By contrast, mainland Europe and the United States struggled with incompatible rail systems for decades (the U.S. only standardized gauges in 1886).

Britain’s political reforms also provided greater stability. One in five adult males in England and Wales could vote—far from universal suffrage but significantly more inclusive than France, where only 0.5% of the population was enfranchised. This broader political participation helped buffer economic shocks by protecting the middle class.

The Revolutionary Wave of 1848

The economic collapse triggered widespread political upheaval—the “Spring of Nations” or “Year of Revolution.” Initial unrest began in Italy on January 1, 1848, when Austrian soldiers confronted Milanese residents during a tobacco tariff protest, leaving six dead and fifty wounded. The first full revolution erupted in Sicily on January 12, forcing King Ferdinand II to grant a constitution by February 10.

Paris exploded in revolution on January 22, with students and citizens erecting barricades and engaging government forces in street fighting. Despite having 100,000 troops in the city, authorities lost control, the king fled, and the French Republic was proclaimed on February 25.

News of these events spread rapidly via railways, steamboats, and telegraphs—technologies that accelerated revolutionary contagion. Vienna erupted in mid-March, forcing the Emperor to promise constitutional reforms, which in turn triggered revolts in Hungary and Bohemia. Berlin followed with massive demonstrations between March 13-18, resulting in 900 deaths before Frederick William IV granted constitutional concessions.

Some nations preemptively made reforms (Netherlands, Belgium), while others emerged relatively unchanged (Britain). Russia’s Tsar Nicholas I brutally suppressed all dissent, widening the gulf between government and intelligentsia that would eventually lead to the 1917 Revolution.

Technology Cycle Impact

Though most revolutionary gains were eventually reversed by conservative counterrevolutions, the events of 1848 produced lasting changes. Italy’s constitution endured until the 1930s, press freedoms expanded, and communication technologies demonstrated their revolutionary potential. Information that once took weeks to travel could now spread in days or even minutes.

The human cost was tremendous: tens of thousands died and many more were exiled. The revolutions transformed the political landscape particularly in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire—setting the stage for the national unification movements and democratic reforms that would reshape Europe in the coming decades.

The third technology cycle: Electricity, Heavy Engineering, and Steel

- The First Great Surge – The Industrial Revolution Textiles and Canals

- The Second Surge – Steam & Railroads – This Page

- Third Great Surge – Electricity, Heavy Engineering, and Steel

- The Fourth Great Surge – I.C.E. (Internal Combustion Engine) and Oil

- The Current Great Surge – ICT – (Information & Communication Technology) – Microprocessors and Telecoms

- Return to the Great Technology Surges Index – Main Page