Technology Cycles: The Depressions and Revolutions

The Five Great Technology Surges

- The First Great Surge – The Industrial Revolution Textiles and Canals

- Second Surge – Steam and the Railroads

- Third Great Surge – Electricity and Steel

- The Fourth Great Surge – I.C.E. (Internal Combustion Engine) and Oil

- The Current Great Surge – ICT – (Information & Communication Technology) – Microprocessors and Telecoms

- Return to the Great Technology Surges Index – Main Page

The Great Surges – The Depressions and Revolutions

Surge One 1790s – The Industrial Revolution Textiles & Canals

In the first surge, canals and textile spinning machines enabled the explosive growth. If a little of something is good then more must be better – right? To a point this is true. However, investments must produce a return for investors. Thus, the bubble bursts in the form of an economic crash. Overvaluations of investments cause a sudden pull back; as investors seek to cut their losses and cover debts as valuations precipitously fall off a cliff.

England was the indisputable leader in the development of technology during the first surge. However, the secondary economies on mainland Europe experienced the greatest social dislocations. The leading economies tend to adjust their rules in governance to support the rapid economic growth. The accommodation of technology development is the reason why one nation pulls into the lead. But the secondary nations, chasing the industrialized leaders, lack a direct line of sight into what is driving their economies. This was certainly the case in France where the first eruption occurred. However this was no way limited to France as we will see in the coming cyclical surges.

The canal age in Britain began in 1767 with the completion of the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal. The canal ran thirty miles from the coal mines on the Duke’s estate at Worsley down to Runcorn in the southwest to the new textile factories.1 In England, the canals – which had started to be developed in Scotland and Wales – began to attract serious attention from investors. The decades following the Duke of Bridgewater’s canal witnessed the construction of more than a thousand miles in new canals. The first canals produced repaid their investors well in dividends and soaring share prices. An Act of Parliament was necessary to authorize the construction of each canal. The new canal system was both cause and effect of the rapid industrialization of the Midlands and the north in England. The period between the 1770s and the 1830s is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of British canals.

In a further development, there was often out-and-out speculation. People bought shares in a newly-floated company simply to sell them for an immediate profit, regardless of whether the canal was ever profitable or even built. During this period, known as “canal mania”, huge sums were invested in canal building, and although many schemes came to nothing, the canal system rapidly expanded to nearly four thousand miles in length. The number of promoted schemes rose dramatically. In 1790 only one canal was authorized by Act of Parliament, but by the early 1790s that number had exploded to more than fifty – more than double the number for the preceding fifty years. This type of activity is a hallmark in the formation of an ominous investment bubble. Mainland Europe had little insight into the formation of the investment in English canals.

The ineptitude of King Louis XVI and his advisors set the revolt in motion as canal mania began to froth. France was in poor fiscal condition after financing the American Revolution. French currency was scarce due to national debt when the situation became much more acute. French speculators added to canal mania as French currency was shipped to England in the form of investments, feeding the investment frenzy.2 When bubbles burst, assets dramatically deflate in value. The existing national debt went hypercritical. To raise more money the King called for the ancient assembly of the States-General, an assembly that had been dead and buried since 1614. The King called for such an ancient assembly because the aristocracy and members of the clergy could always veto the Third Estate within the rules of the States-General. The French Revolution was launched in 1793 as a result. Historian Eric Hobsbawm expressed his opinion that a soaring cost of living in the middle of an industrial depression turned what might have been a small local revolt into the force which became the French Revolution.3 However, I think we can attribute the fact that techno-economic surges were fairly when unknown in Hobsbawm’s day. He couldn’t have known that what transpired in France and around the world was much larger than a simple local revolt. But Hobsbawm was correct about the depression that broke out and spread throughout Europe and abroad.

Surge Two 1848 – Steam & Railroads

By the start of the second surge, all of the new products could not float down relatively flat canals. The Pennines Mountain Range created a good alternative to rail lines to transport textiles and coal that the growth from the first wave had created. The first rail lines were laid where there was real economic opportunity, so the first rail lines were profitable. By late 1844 they paid handsome dividends, four times greater than the prevailing interest rates of the day.

The process for starting a railway company only required some people to form a committee, survey a route, and raise one-tenth of the costs for the projected construction through the sale of scrip (shares). At the time, stock markets did not really exist. The scrip was advertised in newspapers, which provided a dangerous closed circle of constant hype by touting the wealth awaiting investors. More articles brought more subscribers and new schemes to advertise, leading the suddenly booming newspapers to happily print more ballyhoo. This further exacerbated the problem.

Once the minimum bar was met, Parliament only had to make an examination for the project to continue. In many cases, members of Parliament examined projects in which they had personally invested. In 1844, the Railway Act created a new department to do the examinations, but their recommendations were nonbinding, and worse, they didn’t have the resources to investigate all in the flood of the new schemes arriving daily.

By January 1845, 16 new railway schemes were projected, which ballooned to over 50 by April. At the close of Parliament in August over 100 railway acts had passed, authorizing three thousand miles of new track. Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister of England, secured the passage of the Bank Act in 1844, which put a ceiling on the amount of debt the Bank of England could carry as a percentage of their assets. This move was thought would erect a firewall that would protect the economy against speculation.

The Northern provinces were a different story. Northern speculations led to the establishment of Exchange Banks, which provided loans against the collateral of railway shares. They financed up to 80% of the railway’s value. None of the Exchange Banks survived the 1840s.4 As with all bubbles, the law is skirted – if not outright broken. The British railway king, George Hudson, who at one time owned two-thirds of all rail in Britain, not only paid dividends out of the working capital instead of profits, but also mixed his personal rail investments with those for his businesses. He, like many others who followed, was not convicted of wrongdoing, although he clearly manipulated the values.

A June 1845 report listed 20,000 railway speculators, including 157 members of Parliament. Two brothers, who together subscribed for £37,500 were sons of a charwoman who lived off little more than a one pound a week. Others on the list did not live at the address on the application, indicating they were pure aliases. In October of 1845, forty new schemes were announced. Stories of fraud mounted, and by early October the bubble burst. Dropping values causes railway calls, and the dominoes fell over swiftly. Some shares were down by 40% by the end of the month.

No laws for bankruptcy were in existence yet. But by May of 1846, the Dissolution Act was passed because so many railway companies were failing. However, it took years for people to understand the carnage, as it took over a year for the process to truly unwind. By January of 1847 the Bank of England raised interest rates to cover the declines of their reserves per the rules of the Bank Act. On Monday October 17, the “week of terror” began in earnest. Assets were traded at 10% of their value and gold reserves fell to dangerous lows. The Bank of England requested their removal from the rules for the Bank Act to stave off insolvency. They were granted the exclusion, and by 1848 the effects of the crash began to dwindle for England. The opposite was the case for mainland Europe.

Mike Rapport’s 1848 Year of Revolution details the history of the run up and revolutionary crises in mainland Europe that followed the crash in England. Rapport captures the first key phase of the crash dynamic in full high fidelity:

“In France the price of bread, the main staple of the population, rocketed by close to 50%, provoking angry scenes at the bakeries, and foot riots. Furthermore, since people had to spend an even greater proportion of their earnings on food, unemployment in the industrial and artisanal sectors spiraled dangerously upwards, as demands for manufactured goods slumped. In the northern French textile manufacturing towns the numbers of jobless reached catastrophic proportions: in Roubaix some eight thousand out of thirteen thousand workers were thrown into the street; in Rouen, people endured wage cuts of 30 percent to stave off the calamities of unemployment. In Austria ten thousand workers were laid off in Vienna alone, which at a time when food prices were reaching all-time highs and there were no formal governmental programs to assist the poor, was disastrous.”5

This description is the crystal clear fingerprint of a technology Great Surges crash. Rapport encapsulates the dynamic of a surge outside of the leading national economy. As the leader’s economy slows, the chasing national economies spiral downwards. The sudden economic freefall occurs because the currency had already been moved offshore – draining the available currency needed to maintain and run a normally functioning industrial economy. The calls to cover the investments made on margin to make up the difference of the sharply falling share prices began in 1845. It took several years to put up the proposed railway schemes, see them fail, and then dissolved them due to insufficient capital to cover the calls. Later, due to the existence of stock markets for trading developing technology stocks, this will not be the case. Stock markets collapse rapidly, now in days, not years, as was the case in the 1840s.

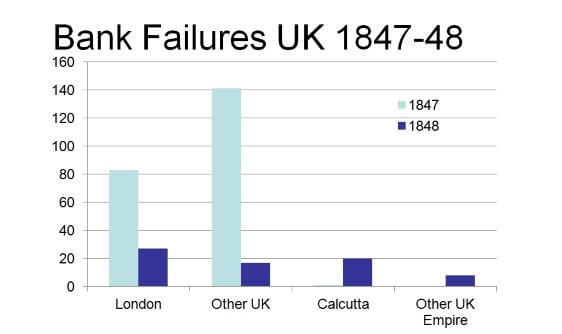

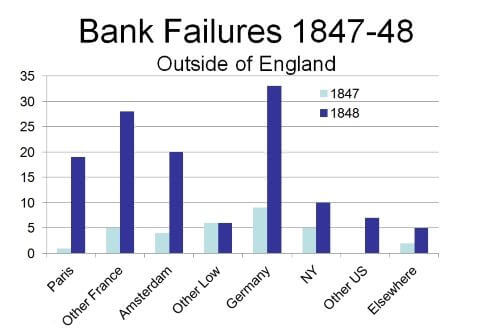

In figures below you can see that in London and the rest of the UK cities, 140 bank failures in 1847 was the peak. For the outlying areas in the British Empire, such as India, 1848 was the year of banking crises. In 1848, France saw over 40 bank failures while Germany experienced over 30. A tidal wave of bank failures deluged mainland Europe in 1848, while England began recovering from the popping of the railway mania bubble. The tentacles of speculation had reached from around all Europe into Britain. As a result, Britain ended up with the best railway system when they left the speculation casino. Mainland Europe, on the other hand, suffered an inexplicable depression with nothing but misery to show for all of the currency turmoil and debt.

England experienced social unrest as a result, but as was the case with textiles and canals, England had already made some changes to laws to arrest the brunt of the impact. In 1844, England passed a law requiring third class passengers to ride on every train in least one train car. In 1846 they passed the Gauge Act, which specified that all trains had to run on the same size tracks. For decades, a lack of uniform gauges plagued the nations that failed to support wave two’s core technologies. Passengers had to travel to a train depot, disembark, and then board another train because the rail gauges were not yet uniform in places like the U.S. and mainland Europe. The U.S. only moved to adopt a standard rail gauge in 1886 – only after the American Civil War, when trade resumed between the North and South, and even then only after the lack of rail standards caused too much difficulty for regional economies.

England also put in place social protections. England and Wales gave the right to vote to one in five adult males; women were excluded as matter of course.6 Clearly this is not democratic, but in contrast with France, the relative differences were striking to say the least. Only a sixth of those who enjoyed the vote in Britain were enfranchised in France – a mere 0.5% of the entire French population. This excluded a huge group of people, since France was the most populous nation in Europe by far.

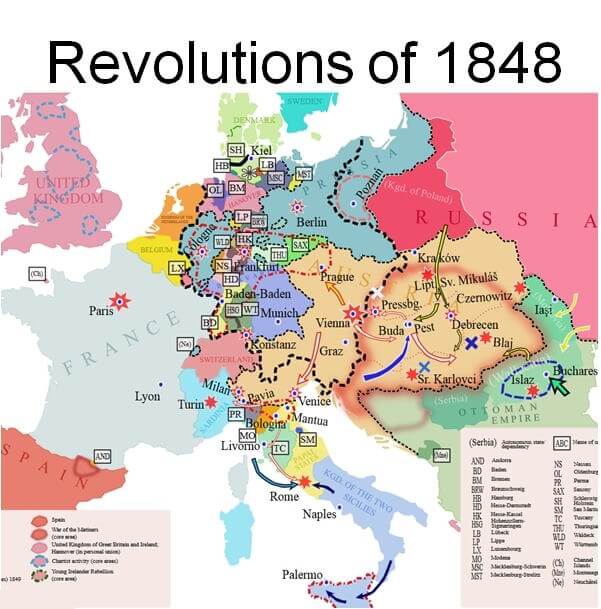

In protecting the British middle class through voting rights and other legal measures, the English not only enabled a more robust economy and a buffer to mute the effects of a crash. The leading industrial nations understood that growth and stability required protecting their growing middle class. The chasing nations, which did not understand the economic dynamics driven by another country, had no such safeguards in place. They did not even consider the need for such legal frameworks, as their thinking was consumed with the wealth of the top 1% in the ruling class. The old saying applies here: The leader catches a cold but the follower nations catch pneumonia. As the suffering took hold as an all-encompassing economic pall, the initial outbreak of rioting occurred in France. The French Revolution had not resolved most issues, as that revolt was ultimately hijacked by Napoleon. In the wake of Napoleon’s defeat the monarchy was resurrected once again in France. The Revolutions of 1848, known as the Spring of Nations, Spring time of the Peoples, or the Year of Revolution, were a series of cascading political upheavals throughout Europe. The following map shows just how incredibly widespread the revolutions were.

Initially, early nationalism was the source for eruptions in revolt. Violence on January 1, 1848, in Italy began when Austrian soldiers taunted residents of Milan during a tobacco tariff boycott. The clash left six dead and fifty wounded. The first full-blown revolution occurred in southern Italy. On the King of Sicily’s (Ferdinand II) birthday, January 12, a crowd gathered – hoisting the Italian national flag, signing songs for a national constitution. The King’s army responded by shelling the crowd. Afraid of losing his entire kingdom, Ferdinand relented and published a constitution on February 10. It was modeled on the French constitution, enacted 34 years previously, therefore a long way from enfranchising the masses. The revolts spread upwards through Italy. Gathering en masse in Rome, crowds protested in front of the Vatican and demanded a national constitution. Most of the other provinces committed to a constitution but two did not. It took larger European events to provide the Italian nationalists the opportunity for a unified Italy.

On the morning of January 22, Paris awoke to a dreary sky and heavy rains. As seven hundred students crossed the River Seine singing the Marseillaise, the national anthem of France, crowds joined them and surged across the Place de la Concorde, only to be pushed back by the dragoons. As blood began to spill, fighting exploded across the city. Barricades were erected and manned overnight. Despite the over 100,000 troops in Paris, the revolutionaries either won the street fighting or turned the troops over to their side. The King fled the country and after some hasty meetings, a provincial government was set up. In the early hours of February 25 the Republic was proclaimed for France (again).7 Revolutions of 1848 Map – source see Footnote8

Rapport’s wrote: “Word of the February days in Paris spread like a dynamic pulse and electrified Europe, hastened by the wonders of the modern world: railway, steamboat and telegraph.”9 The outbreak of dissent spread across Europe thanks to new technologies enabling faster communications vehicles. Demonstrations in Vienna escalated as the suburban workers finally crashed through the city gates. The working class attacks on factories and shops went on unchecked. At 5 p.m. on March 15, an imperial proclamation read out to the city of Vienna requested that all of Austria send delegates to discuss a constitution. This quieted the riots in Vienna but unleashed revolts in the eastern portions of the Austrian Empire. Hungarians and Czechs revolted on the news of the Emperor’s capitulation, so constitutions were also promised to the Hungarian and Czech peoples.

As absolutism in the Austrian Empire collapsed, the other portion of Germany that had not yet yielded, Prussia, came under attack in Berlin. Between March 13 and 18, people began demonstrating. Middle class property owners dressed in top hats, journalists, shopkeepers, teachers, and industrial workers like those from the Borsig locomotive works still wearing their oily smocks, picked up their hammers and marched to man the barricades. The Emperor of Prussia, Frederick William, sent the army to restore order in Berlin. The result was a massacre – nine hundred people were killed in one afternoon’s fighting. On March 21, the King read a declaration that troops would leave the city and he would merge Prussia into greater Germany. The next day, Frederick William finally announced that he would grant a constitution. He wore on his hat’s brim the German tricolor – the black-red-gold that had been outlawed as revolutionary – as he vacated the city for safer climes.

Some countries like the Netherlands and Belgium made concessions before any serious groundswell occurred. The British Isles emerged essentially unaltered because the middle classes, from the wealthy to the shopkeepers, supported the government since the British had already moved to protect their middle classes. Further, the protestors refused to commit acts of violence. There was rioting in Glasgow when a bill for a tax increase was announced. The following day in London 10,000 people listened to speakers, but only a small group of protestors vandalized windows and street lamps. In the end it was a very civil demonstration.

In Russia on the other hand, the Tsar brutally suppressed any revolutionary opposition – real or imagined. The regime and the intellectual vanguard had interacted with some give and take before 1848, but would pay a ridiculous price for its position after 1848. Given this tack, the chasm grew so wide there was no way to bridge it, and the Russian Revolution of 1917 was set in motion by not permitting any liberalization in government.

As it turned out these and a few other events were the high water marks for populist revolutions in 1848. The revolutionaries had not planned the outbreaks. The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and lower class workers, which did not hold together for long. Most of the prosperous middle class would have been thrilled to receive constitutional monarchies. However, since the middle class was split between the working poor and those getting ahead, once the new ad hoc groups had their advantage, they splintered in opinions regarding next steps. They effectively handed the power back to conservative aristocratic forces, which ruthlessly wiped the gains away. Many of the revolts aimed to create nations that reached across borders to protect the entire middle class. When the time came for those decisions, nationalistic views invariably won out. But there were still real gains from the revolts. The constitution for Italy effectively served until the 1930s. The relaxation for freedom of the press coupled with the speeds that information could move were big wins for the people. The news from the French Revolution in 1792 took weeks for news to be carried on horseback or under sail. “In 1848, thanks to steamships and a nascent telegraph system, reports were being heard within days or even minutes!”10 Tens of thousands of people were killed and many more forced into exile. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire.

Surge Three 1890s – Electricity, Steel & Heavy Engineering

In 1870 England, France, Germany, and the US were the principal industrial nations producing more than 80% of the world manufacturing output.11 Steel output from 1870 to 1890 had multiplied twenty fold in the big 4 (UK, Germany, France & US).12 Affluence from the 1870s to World War 1 based on booming business in Europe is referred to as the ‘beautiful era’ (Belle Époque).13 Economic historians have tended to fix their attention on two aspects of the era; redistribution of economic power, meaning Britain’s relative decline and the absolute advance of USA and Germany.14 This was a distinct shift in surge dynamics, as all other surges, before and after Great Surge three, a single nation led the core technology development. The 3rd surge with the UK declining and Germany and the US ascending is unique. Perhaps we should call the 3rd surge the transitional Great Surge in the Industrial Revolution.

Depressions or major economic crashes are representative as the center of a Great Surge. Therefore it is a pretty safe bet when one sees a worldwide depression that one knows where we are in the Great Surge. The structure of a Great Surge is the same; however, the history for how and when it is propagated is always distinctive. Another reason the 3rd surge was unusual was that the worldwide depressions of the 1890s arose in different countries at different times. The US which had only for the first time jointly taken the lead from England in surge three is a perfect example of the mixed timings of this unique surge. In the US the Panic of 1873 was blamed for setting off the economic depression that lasted from 1873 to 1879. That period was at the time called the Great Depression. Then an even greater depression of 1893 received that label, which it held until the greatest US depression hit in the 1930s—now known as The Great Depression came along. The depression of 1893 was then renamed to the Long Depression as it ran on and off again from 1873 through the 1890s. The Long Depression occurred at different times in England, France, Germany, and the US.

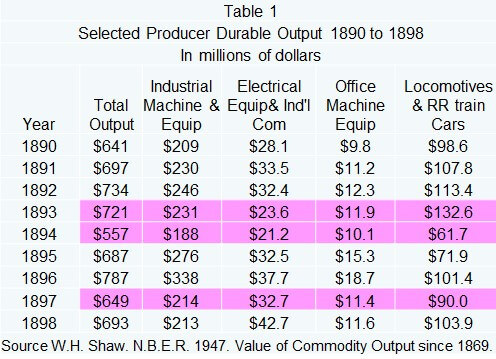

Now if you are wondering if the Long Depression was a real depression, let’s look at some summary statistics from the US National Bureau of Economic Research (N.B.E.R.). Unemployment reached 20% and 800 Bank failures were recorded from 1893 to 1897. That number exceeded any number other than The Great Depression (1929). By mid-1894, 156 railroad companies with a market capitalization of $2.5B (in 1894 dollars = $92B 2024 dollars) representing about 30,000 miles of train tracks were all in the hands of receivers (bankrupt). This N.B.E.R. data provides the incredible amplitude of The Long Depression (1890s). The data cited was sourced from Charles Hoffmann’s dissertation at Columbia University written in 1954. Hoffmann further explains why the secondary dynamic was so unusual for The Long Depression. Economic peaks were recorded in July 1890, January 1893, December 1895, and June 1899. Economic troughs were also recorded May 1891, June 1894, and June 1897. Unimaginable booms subsequently reversed approximately a year apart! A triple bottomed depression in 8 years? The economic equivalent of having been financially whipsawed three times in a decade no less.

“Broadly speaking the new energy sources in electrical and chemical energy, or those associated with the new energy sources about to compete with steam – do not as yet seem quite imposing enough to dominate the movement of the world economy.”15 The final reason the 3rd surge was special was the industrial economies for the first time in history began to tilt towards the industrial technologies. The 3rd surges techno-economic drivers began to fuel the broader economy. But there were still huge swaths of the economy which were dependent on farming at the same time.

Please don’t misinterpret the explanations in surge three rareness. It unfolded in a fairly typical way starting with the Baring Banking crises. The Baring bank bet heavily in South America, primarily on South American railroads, in an effort to keep up with all the other institutions making money in the investment gambling house of the 1890s. The railroad mileage in Argentina had doubled within 5 years.16 The Baring bank would go bankrupt and their investments reached so far internationally that the richest individuals in the world had to band together and step in to stop the financial dominoes falling. An international consortium assembled by William Lidderdale, governor of the Bank of England, including the Rothschild’s and most of the other major London banks, created a fund to guarantee Barings’ debts, thereby averting a worldwide banking catastrophe. Nathan Rothschild remarked that if they had not intervened, the entire private banking system of London would have collapsed which would have caused an even larger economic catastrophe.

Americans had likewise participated in creating froth for the bubble. US investments abroad from 1892 to 1897 had risen by ~$250 million, most of it going into Argentina. FN Hoffmann 157. On May 5, 1893, the Dow Jones Index suddenly plummeted by more than 24%! It would mark the worst intraday sell-off in U.S. history at the time, a record that would stand until The Great Depression when the Dow would shed 89% of its value from September 3rd, 1929 to July 8th, 1932.17

Another response which has repeated itself was the rise of populism in the 1890s.18 In the US William Jennings Bryan was the populist leader who also supported the literal understanding of the Bible and banning the teachings of Charles Darwin. (FN Empire 38). Sounds a bit familiar to the post 2010 crash doesn’t it? Populism activated again, raging around the world in response to the 2009 crash (aka the Great Recession). Populism’s rise in reaction to The Great Depression was channeled into right wing fascism which would drag the world into the most horrific war ever fought.

Housing activity was another factor in the third surge which was identical with coming surges (4 and 5). In the mid 1890’s building reached a trough in cities and did not recover in many cities till 1905 in the US.19 The reason housing contracts seemingly as a delayed reaction to depressions is because speculators who were making large returns on their investments in the run-up to the crashes are frantically seeking asset classes which can generate huge returns as the bubbles in the core technologies driving the Long Cycle pops. Later you will see in Long Cycles 4 and 5 exactly how this dynamic have reoccurred. Carlota Perez explains the theory in her book Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages.

What was different in the 3rd surge was that there were brand new nations and intense flag waving nationalism. Germany and Italy pushed towards unification while at the same time the Austrian Empire, one of the largest empires ever, created an enormous vacuum through its decline. The Austrian Empire had been the weld of the European political world. The two largest Empires in simultaneous decline was likely central cause for World War 1. To this day there has been no historical consensus for the primary driver for WW1. I think these dynamics created a transitional Great Surge due to all the new nationalism as older Empires faded and therefore no nation held sway on innovation development. WW1 was the first industrialized war with 20 million people having died. It is well understood that the armistice terms were so hateful from WW1 that they were the spark which ignited WW2 on the heels of the crash of Great Surge four where another 85 million people were killed. Great Surges are something tectonic plates on the world economy. The intense magnitude of the forces when Great Surge tectonic plates collide, results in titanic earthquakes and volcanoes. The same is true the forces at the center of Great Surges.

Because so little has been written on the Long Depression or the US Panic of 1893, I will be the first in line to buy a book should anyone publish one on these topics in future. The following link is to: a more detailed description adapted from Clément Juglar’s book he wrote in 1893.20 Interesting to note that Juglar was a Frenchman, but the Panic of 1893 was a worldwide event so this should not be surprising. He is also famous for his study in short business cycles which run from 7 to 11 years. Later Joseph Schumpeter in studying business cycles read Juglar’s publications and included some of his theory in his 1939 book on business cycles. The shorter cycles were referred to in the 20th century as Juglar cycles. After the Keynesian revolution took hold Juglar’s cycles were discarded by the field of economics.

Surge Four 1929 I.C.E. (Internal Combustion Engine) and Oil

Henry Ford found the way to mass-produce a car cheaply and without the need for roads in order for the car to work well. The Tin Lizzie, as the Model-T came to be known, had thin tires but high ground clearance, which enabled its use on farms and on the commonly unpaved, muddy roads of the day. Ford also vastly improved the process that Arkwright began at the Ford River Rouge plant. There, freighters brought tons of raw materials to the enormous series of buildings, housing everything from steel production to automobile assembly facilities. Ford even had dynamos built on the property so that they could produce their own electricity to power the plant. He did this for practical reasons. No power plant large enough existed to provide the amount of electricity the massive Rouge manufacturing plant consumed during operation.

At the same time, early planes were being built with internal combustion engines. Wilbur and Orville Wright designed and built their Wright Flyer based with a small 25 horsepower engine. The internal combustion engine, though young and not yet powerful, quickly unseated steam as the propulsion engine for the 4th Great Surge. Cars, trucks, and planes began to take market share from the railroads. The encroachment of gas engines forced many railroads into bankruptcy when The Great Depression struck. Many of the canal operators went bankrupt or merged during the second surges depression.

At the turn of the century, roughly three hundred carmakers were whittled down to just a handful. In the U.S. the major carmakers were Ford, General Motors (GM), and Dodge/Chrysler. Though known as the Big Three, the competition during the cycle was primarily between Ford and GM. Ford roared out to a huge lead with the Model-T. But Ford produced the car far beyond its market desirability. GM released more models with more options and updates. GM took the lead from Ford’s gaffe, and on the back of a structured management system for all its auto units, did not look back for the remainder of the 3rd Great Surge.

As industries were again remade to incorporate mass production and the internal combustion engine, everyone sat up and took notice. The U.S. had sole possession as the leading nation for industrialization. The roaring twenties was an apt name for the gilded age that erupted in the 1920s. As the economy expanded, so did speculation on the stock market. The Dow Jones21 quadrupled in value from the early 1900s to 1929. Investors yet again drove the valuations in stock far beyond reality. The stock bubble suddenly popped, and The Great Depression descended worldwide – bringing the roaring twenties to an abrupt halt.

The first groups providing the tinder for the fuel of the surge crash were the new brokerage houses that whipped up the investing frenzy. Income in the U.S. did not create the investment cash required, so they allowed investors to buy on margins of 80%. Investors only had to pay the 20% difference between the value in their stocks and what they had paid for them. As the market rose, there were few margin calls. But when the market began to fall, another viscous surge ensued, just like the ones in the prior surges with the rail scrip calls. Legitimate companies’ stocks had to be sold to cover margin calls, further reducing the stock prices and forcing ever direr margin calls.

At a time when a 20th of the population controlled 90% of all wealth, the stock market was dominated by wealthy speculators. Among the rich speculators, two groups stood out. The first group was those who made their fortunes in the automobile industry. The list was a who’s who from the auto industry: Walter Chrysler; William Durant, founder of GM; and John Raskob, director of GM, were just a few of the extremely wealthy who pooled their money into enormous investment vehicles called pools. William Durant was forced to resign from GM when he lost his fortune speculating on GM stock. He temporarily rebuilt his fortune through pools as his stock portfolio bulged to $4 billion in 1929.

The news of the pools brought in the second group: ordinary investors who imitated the rich in seeking the same type of scaled leverage. News stories, reporting that pools were buying certain names, were planted to pump up stock values. In conjunction with all the monkey business going on in the stock markets were the wholly owned subsidiaries of the tech giants of the day. These wholly owned subsidiaries were created so that companies could in effect “play” the market during its spectacular rise. Subsidiaries were a required vehicle since it was illegal for companies to “play” the market directly – just another example of how the letter of the law is skirted when the bubble gets so large that people think it is simply foolish not to participate. The intent of the law was clear not only that they should not – but could not do this legally. There was a ‘suckers’ rally in 1930, but nothing could stop the total capitulation of the market reaching the bottom in 1932.

The 1930s bore witness to unemployment rates reaching 25% and the virtual destruction of the American economy. Because President Franklin Delano Roosevelt did as much as the nation would allow by creating the “alphabet soup agencies” in his New Deal plan, the people felt the government made an earnest effort to support them. The U.S. government took over the bankrupt railroad industries pension system which then was expanded to cover universal Social Security for all American workers in the 1930s. The effort to get the nation back on its feet reduced the social impact so that it did not generate a revolutionary response in the US. But as was the case in the prior surges, the major social responses came from mainland Europe and the secondary industrial nations. The U.S. middle classes perceived their government as working for their interests, so the U.S. mirrored the British middle class in the prior surges and did not revolt in the streets after the crash.

The rise of new nations such as Germany and Italy featured an extraordinary emotional response in nationalism. However the colossal reparation agreements for the end of World War I created financial chaos in countries like Germany. A new economic term was created to describe the instability – hyperinflation. The inflation rate reached such outrageous proportions that workers were be paid twice a day so that they could run to the store at lunchtime to buy food as inflation skyrocketed upward on an hourly basis. When the currency was finally replaced in the mid-1920s, the exchange rate was a single new Mark for every 25 trillion Mark note! On the heels of this financial debacle came the crash of 1929, where the values of all assets then contracted through rapid onset deflation. The completely destabilized financial situation enabled fascists, with agendas to turn back the clock by manufacturing scapegoats and blaming their minority social groups, to seize power. Austria, Italy, Germany, and Spain saw the terrible fiscal conditions the fascists utilized to confiscate power through widespread violence and intimidation throughout The Great Depression. This ended with World War II (WWII). The highly industrialized warfare produced the worst human slaughter mankind has ever seen. Only a few decades after the war to end all wars, WWI, we saw WWII destroy Europe, North Africa, and Asia.

Surge Five 2001 ICT (Information & Communication Technology) – Microprocessors and Telecommunications

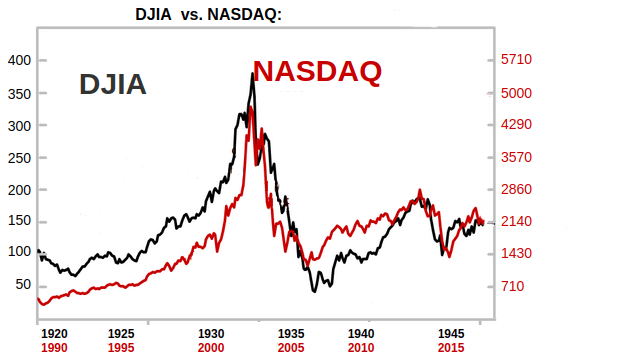

The heady 1990s were similar to the roaring twenties. The economy grew by leaps and bounds. This time the NASDAQ stock exchange was the home of latest technology companies. The NASDAQ grew from 100 points in the early 1970s to over five thousand points at its peak during what is called the dotcom era in the 1990s. The dotcom era saw explosive growth in the creation of the internet for use with the PC. People invested in any company in the latter 1990s that hosted a website. The paper valuations of dotcom companies, producing zero profits, started to exceed those of traditional companies producing real sales in the billions with real profits. The height of the frenzy is illustrated perfectly by AOL’s merge with media giant Time Warner. AOL’s CEO was even named the CEO for the merged entities.

The investment trusts and pools of the 1920s were the mutual funds of the 1990s. There were 1,100 mutual funds in 1990, and just seven years later there were over six thousand with trillions of dollars invested. As the rules for margins had changed to require 50%, investors took out home equity lines to skirt the rules and invest in mutual funds. Chat rooms, which existed as bulletin boards before the internet existed, reinforced the vicious cycle. In those chat rooms, some promoted stocks to simply pump up their value through false statements. To add to the noise, there were cyber cheering sections. This was the case for the Motley Fool and their bulletin board, “IOMEGA heads” with their followers’ zeal for IOMEGA Corporation. All of this hype propelled absolutely unreal stock valuations higher and higher. In January 1999, when the Marketwatch.com stock was first sold, it started at $17 a share. By the end of the first day of trading it had gone up in value to $97.50. All this fuss over a stock which was a news portal listing investing articles?

Of course the same excess valuations caused the initial pullback, then renamed the dot-bomb era. Because U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan allowed interest rates to go lower, the recession was only felt initially in the business sector from 2000 to 2003. As the stock market could no longer sustain the double digit growth rates, investors sought new markets. The bubble in capital, fueled by all the home equity loan activity, subsequently moved into the real estate markets. In late 2006, the real estate market, like the stock market in 2000, could no longer support the huge growth rates. Home values began to decline, creating the monster that ultimately brought down the entire house of cards in excess valuations and precariously over-leveraged investors. Prior to the housing bubble, people bought homes to live in – not as investments to quickly flip as a short-term investment vehicle.

As with the last crash, companies skirted the law again. Homes were sold with little to none of the legal controls in place to ensure that the borrower could afford to repay the load – or even if the borrower actually existed! This created an enormous pile of bad mortgages that could not be resold as usual. These bad mortgages were thrown together in tranches and marked at the highest quality level, and then the market suddenly found buyers for these subpar mortgages. The speculators’ casino finally began closing its gambling windows in late 2008 in the current surge, as the subpar mortgages began to default. The defaults affected cities’ retirement funds to large investment houses as the calls went out to cover falling asset prices. In September 2008, two of the largest investment houses in the U.S. – Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch – were sold for fire sale prices. The bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers quickly followed and slammed shut the casino window as no buyer at any price could be found. The Great Recession was all over us by 2010.

Though the circumstances were different, it is absolutely remarkable just how identical the drop in stock values was comparing the current wave’s crash to the one from the Great Depression. The core drivers are so similar that the outcomes are virtually identical. The next figure demonstrates the striking resemblance between the market performance of waves three and four. Clearly the relationship is not a causal or accidental one.

In the far left hand figure22 the DOW’s performance (in black for surge four) from 1920 to 1940 is shown with the NASDAQ’s performance from 1990 through 2010 (in red for surge five). The stock markets had identical movements for the 20 years up to and through the crashes for the Great Surges three and four.

The DOW from 1920 to 1940 contained all the leading edge tech companies like GM and Ford. From 1990 to 2010 the tech heavy index was NASDAQ, housing everything from Apple to Microsoft. The economic performances were identical because the same techno-economic factors were at work in both cases. The only substantive difference was the Federal Reserve in 2009 reacted and lowered interest rates to zero to dull the corrosive effects of the Great Recession. We can see this change reflected in the performance at the 1940/2010 point in the graph. During the Great Depression nothing was done at the Federal monetary level, making the crash far more catastrophic.

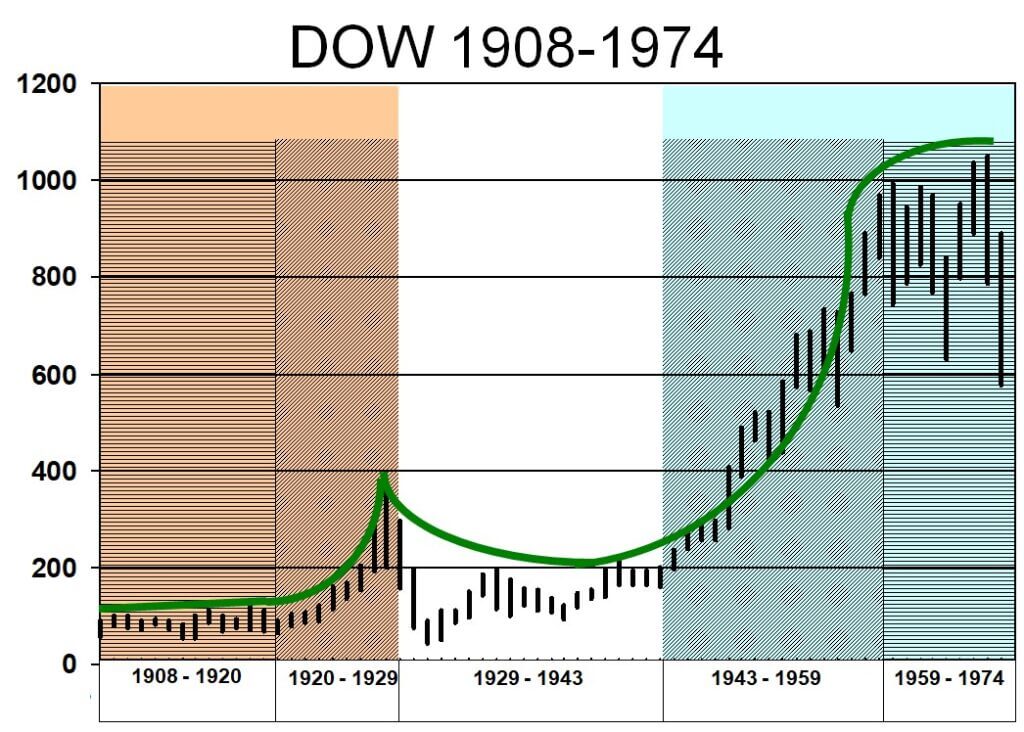

Graphing the actual data of the DOW for most of surge four, you can recognize why I use the curve shape to represent the surge. The green trend line merely follows the data which shows the highs and lows of the DOW Jones for each year from 1908 through 1974.

Before we expand on this salient point, let’s return to the byproduct of the crash. In 2009, the U.S. unemployment rate suddenly shot up to more than 10%. Movements inside the U.S. like Occupy Wall Street staged demonstrations in response to the economic collapse, as the underprivileged or least skilled workers were again most punished with the highest unemployment rates and the bleakest outlooks. Again, the leading economy did not receive the greatest impact. Riots broke out across Europe, most notably in Rome and Athens in 2011. Countries like Greece, where unemployment was still around 25%, suffered from extremely unsettled economies.

The social responses with the largest impacts were reflected in the Middle Eastern nations. These uprisings, called the Arab Spring, rocked the world in 2011. The West had backed dictatorship rule in the Middle East since the end of WWII. The dictators were not all cut from the same mold; some were friendly to the West and some to East in what can be viewed as the extension of the Cold War fought by proxy. But all the dictators had at least one thing in common through the creation of a structural kleptocracy.

In Voices of the Arab Spring, a group of educated revolt participants retell stories of torture, secret police, and cruelty.23 They sketch out the dictators’ outlandish lifestyles in nations suffering from severe underemployment and poverty. Though many of the nations had representative bodies, no one dared to speak up to address substantive issues out of fear of terrible retributions. The events of the Arab Spring uprisings began in Tunisia on December 17th, 2010. Once the economic situation deteriorated to beyond hopeless, a 26-year-old fruit vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, immolated himself in a provincial town in the region known as the forgotten ones. He set himself on fire in front of the municipal building in Sidi Bouzid. This rural town is 200 hundred miles south of the Tunisian capital of Tunis. Tragically, this radical form of suicide was not the first one of its kind. Hundreds of youths protested, and the number of clashes between protestors and “security” forces grew. On December 27th, the dictator of Tunisia Ben Ali, announced on TV that rioters would be punished and he would create more jobs.

Though the regime’s spyware program attempted to prevent the revolts from being shown and spread on Facebook and across smartphones, they were unsuccessful in stemming the technological tide. The protest grew larger and more vocal. On January 13th the chief of staff of the Tunisian armed forces refused orders to use the army against the protestors. The next day, Ben Ali fled to Saudi Arabia with his family. The first of the aging dictators was toppled at the start of the Arab Spring.

The day after Ben Ali fled Tunisia, Muammar al-Quaddafi announced on Libyan TV his sympathy for Tunisian people and praised himself as the model for “leading people’s revolutions.” By February 17th, demonstrations began in his country. Though the Quaddafi regime shutoff the internet after seeing the results in Tunisia, they left on the cellular towers, enabling communications for the protestors. Within six days, Eastern Libya was liberated. The dictator’s regime did everything they could to remain in power, including bombing the Libyan people with missiles. The UN enforced a no fly zone, and the armed resistance took until the end of summer to topple Quaddafi.

The revolt moved much faster in Egypt. Khaled Said, a 28-year-old Egyptian was tortured to death by Hosni Mubarak’s secret police in 2010. With the success from the people of Tunisia, a Facebook page was launched titled “We are all Khaled Said.” Two images of Khaled’s face were posted on the page: One of his healthy and smiling face and the other of his face ravaged after torture. On January 25th, 2011, Egyptians headed en masse to Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, heeding a call to march from the Facebook page. On February 2nd, criminals were released from prisons and sent into the square on horses and camels with sticks, knives, and swords to attack the protestors. The uprisings spread and grew, and on the 18th day of protests, the military assumed Mubarak’s power.

As the events quickly unfolded throughout the region, the poorest nation, Yemen, burst into protests on January 22nd. Sixty percent of Yemen’s population lived below the poverty line, and many of them had been in the middle class but had descended into the world of the working poor. The morning after Mubarak’s fall, citizens spontaneously came out to demonstrate at the University of Sanaa. Though the people of Yemen attempted a peaceful coup, the dictator of Yemen, Ali Abdullah Saleh, sent a helicopter to machine gun the non-violent protestors. Fighting immediately ensued. Saleh was injured in an attempt to assassinate him during the summer and went to Saudi Arabia and transferred power to the Vice President in November 2011.

As awful as the loss of life in Yemen was, what occurred in Syria was far worse. Over 200,000 Syrians have been killed in the Syrian civil war. From 2012 to 2015, tens of thousands – entire neighborhoods – have fled after giving up hope that the civil war would end. The dictator still in power over a portion of Syria is Bashar al-Assad. The Syrians began to protest on March 15th the harsh beatings and torture administered to school children of Daraa who wrote anti-government graffiti on their walls. From there, protests escalated and the dictator went so far as to use chemical weapons on the citizens of Syria. Because Assad has a close relationship and support from another infamous kleptocrat, Vladimir Putin of Russia, he maintained his grip on power until 2024. That was more than a decade after Assad had gassed Syrian people to stay in power.

Why this matters today

Because many of the industrialized nations, including the US, elected populist politicians who have hijacked the narrative for the cause of the depression/recessions in the 5th great technological cycle, we are all stuck in the Turning Point like from the movie Ground Hog day. I covered this in the great surges history page therefore please click here to jump to that page to read through why we are stuck. Carlota Perez covered this issue in more detail in her blog post.

The revolts like the ones outlined above were the foundational pieces of the Arab Spring. Dictators like Bashar Al-Assad were backed by Russian weaponry created a tsunami in mass migration out of the Middle Eastern region for hundreds of thousands seeking safety. That migration into primarily Europe was the excuse used by right wing conservative groups firing up populist support again. Europe is not alone in this. In the US right wing conservatives are singing the song as the Europeans, except their complaints center on the immigration from Central and South America. The right wing wraps themselves in the flag claiming that the problems in their nations stem from the immigrants, minorities, and all the members of opposition political parties. It is a distant replay of the forces which boiled up in the 1930s in Europe. The real economic cause for the economic instability was not immigration, legal or otherwise. The real cause is the crash from the current Great Surge. That is the cause driving economic turbulence in the US (as well internationally).

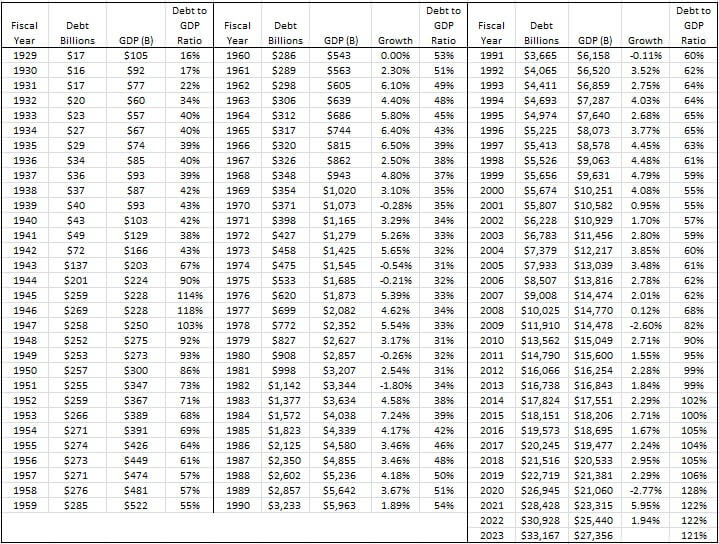

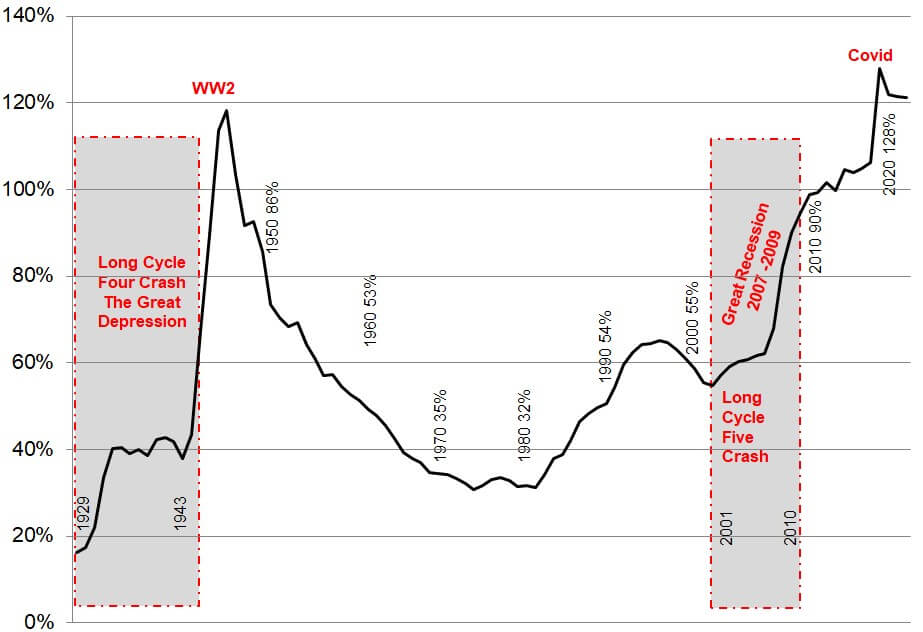

Because we are stuck in this ongoing turbulent economy, one where increasing taxes go to service the burgeoning national debt, forcing services to be reduced or cancelled outright. And all of that simply to service the interest only.24

The issue that absolutely none of the politicians are addressing is the real national debt.25 The debt is above the percentage of debt to GDP which the US saw when they borrowed heavily to fight and finance all of the Allies to fight WW2 (1945-1947). The ratio climbed over 100%. But then spending was reduced as a percentage against growing revenues as the economy grew. In the current surge – we have had the mortgage crises in 2010 and then Covid. Therefore the debt ratio climbing during the 2000s was understandable. However, the economy was very healthy before 47 took office. None of the talking heads are offering spending reductions or tax increases despite taxes being at record lows. Corporate taxes are essentially now non-existent as the lobbyists for special interest groups lobby congress and individual Supreme Court justices for loop holes for huge corporations. This on top of the huge concessions companies have negotiated with states where they have buildings and employees. Large companies are effectively paying zero taxes as a result. The declining middle class increasingly is forced to shoulder the more of the burden that the rich and corporations have find ways to shirk. The health of the US middle class continuous to collapse under the weight of this ongoing bank heist from the federal coffers from the freeloading rich and the multinational corporations.

On the far left side you will see a table listing the GDP an the US National Debt since 1929. It also lists the debt ratio. The ratio is significant as inflation over the last 100 years has changed the amount of dollars but the relative ratio is still very important. To illustrate why on the graph next to it surge 4 and 5 crashes are highlighted in gray boxes. What immediately jumps out. Yes when Depressions hit – national debt increases to extreme levels. But then the debt ratio lowers. The debt has remained at depression level spending because the populist agenda is not course correcting as it did in response to the prior two surge crashes. Instead the politicians from the left and right, there is no center as all of the middle ground politicians were sent packing, continue to buy votes by increasing spending as if more than half of the current US tax revenues is not enough of the US revenues going to service the interest payments of the debt.

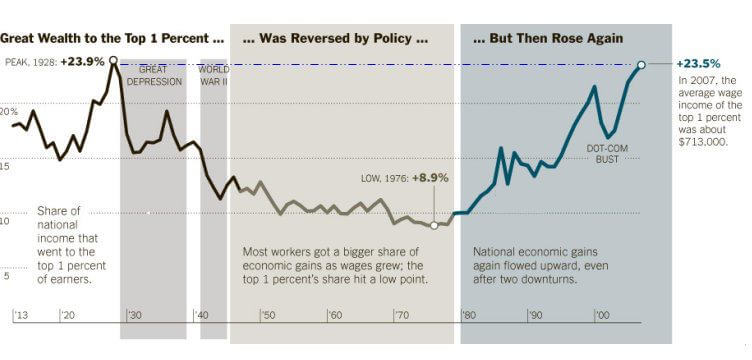

On the left you will see a chart of how the richest 1% of US citizens hold a quarter of the nations wealth when the crashes occurred for surges 4 and 5. The wealth was re-attained after The Great Depression. However after the crash in the current surge the 1% wealth has continued to climb. Again because the wealthiest people and companies have tax loopholes or just an outright smaller tax percentage they are required to pay, both the wealth for the 1% and the US national debt continue to remain sky high.

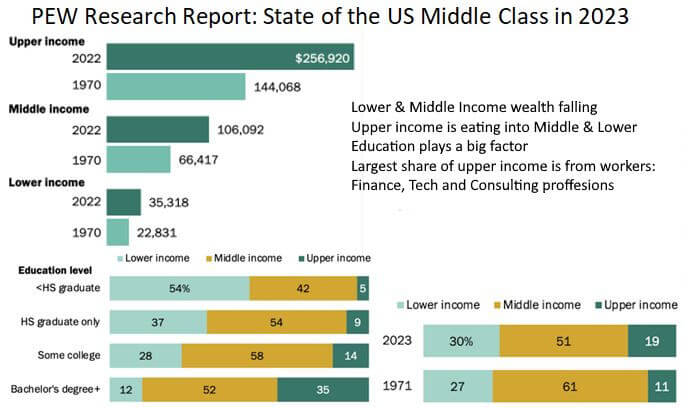

Two thirds of the US economy is driven by consumer spending annually. If the middle class can’t reacquire the wealth that made US have the stellar economy it was after WW2,26 the future growth for the economy is in very real peril.

Why? Well understand two things. First the 1% does not spend like the middle class. There are just so many chairs and groceries the 1% purchase verses the enormous spending of the many more people who constitute the middle class. Therefore the small percentage who are top earners in the US can not fuel the US economy. Lastly in order for the US economy to continue as it has for many decades it must create something like 200,000 jobs every quarter just remain flat. Anything below that and the economy begins to contract. The 1% and the GDP debt ratio are erasing the possibility of a future healthy or even a flat economy. The expenditures servicing the national debt can create a self sustaining negative cycle of spending reductions which will ultimately require enormous budget cuts. The fantasy of the politicians who say the debt doesn’t matter is now coming home to roost.27

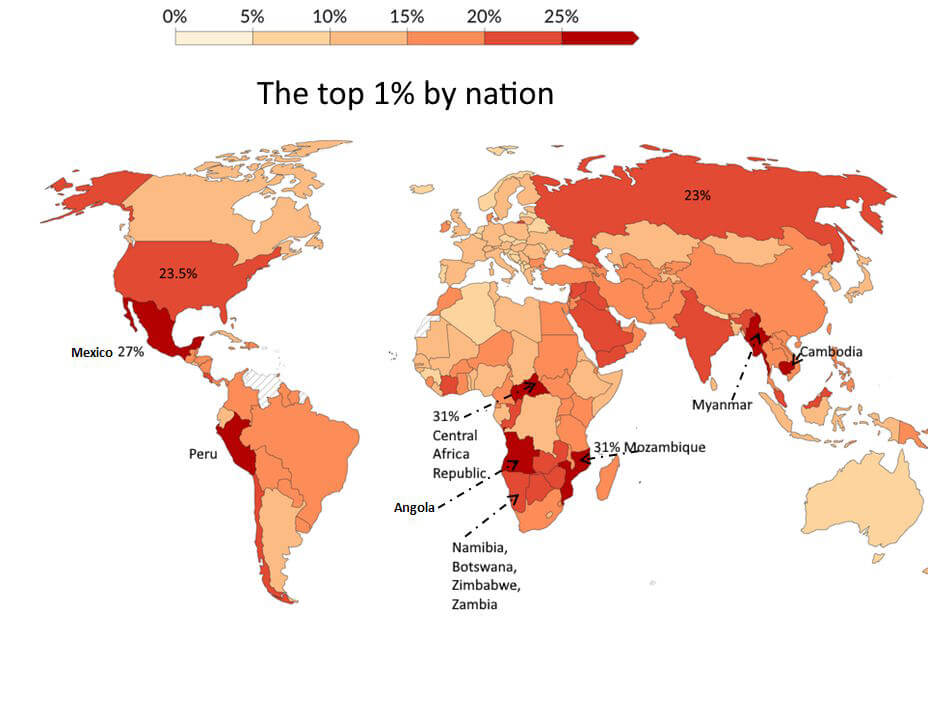

I provide the final two charts for those who think the economy will continue to grow jobs in the face of ever increasing debt payments. For those who say – it is really great the US is dominated by the richest 1%. It shows just how wealthy and powerful the US is. The first chart on the lower left shows that other countries dominated by the 1% are from the likes of: Russia, Mexico,28 Namibia, and Cambodia. Now for those who say the US has the largest economy and therefore comparing the US to them is irrelevant. I respond and conclude with the final slide from the PEW research centers study on the state of the 2023 US Middle Class.29 The aggregate middle class (middle incomes) is contracting, and has been for decades. The lower class has also been growing as members of middle class are falling down into the working poor world.30

The Footnotes follow for this page

- Devil Take the Hindmost. A History of Financial Speculation. By Edward Chancellor Published by Plume 2000. Page 123. ↩︎

- Manias, Panics and Crashes. A History of Financial Crises. By Charles P. Kindleberger and Robert Z. Aliber. Published by Wiley & Sons 2005. Page 112. ↩︎

- Age of Revolution by Eric Hobsbawm. Vintage; Trade Paperback Edition 1996. Page 61 ↩︎

- Devil take the Hindmost. A History of Financial Speculation. By Edward Chancellor Published by Plume 2000. Page 134. ↩︎

- ear of Revolution 1848 by Mike Rapport Published by Basic Books 2008. Pages 36-37. ↩︎

- 1848 Year of Revolution by Mike Rapport Published by Basic Books. Page ↩︎

- 1848 Year of Revolution by Mike Rapport. Published by Basic Books 2008. Page 57. ↩︎

- “Revolutions of 1848 in Europe (pasopt eng)” by Dahn – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Revolutions_of_1848_in_Europe_(pasopt_eng).svg#/media/File:Revolutions_of_1848_in_Europe_(pasopt_eng).svg ↩︎

- Ibid Page 57. ↩︎

- Ibid Page 106. ↩︎

- The Age of Empire: 1875-1914. By Eric Hobsbawm. Vintage Publishing; Reprint edition 1989. Page 43. ↩︎

- Ibid Page 35. ↩︎

- Ibid Page 46. ↩︎

- Ibid Pages 46-47. ↩︎

- Ibid Page 48. ↩︎

- Ibid Page 35. ↩︎

- The Dow did not return to the peak close from September 3rd, 1929 for another 25 years (until November 23rd, 1954)! ↩︎

- The Age of Empire: 1875-1914. By Eric Hobsbawm. Vintage Publishing; Reprint edition 1989. Page 36. ↩︎

- The Depression of the Nineties. By Charles Hoffmann, Dissertation/PhD, Columbia University 1954. Page 140. ↩︎

- A brief history of panics and their periodical occurrence in the United States. By Clément Juglar. Published by G.P. Putnam’s Sons. 1893. ↩︎

- The DOw Jones Average is the listing of the top 30 industrial companies on the US stock market. ↩︎

- Source: http://www.forecast-chart.com/great-depression-stock-chart-nl.html ↩︎

- Voices of the Arab Spring, Personal Stories from the Arab Revolutions. By Asaad Al-Saleh. 2015 published by Columbia University Press. ↩︎

- Please don’t try and repeat the drivel that denigrating and firing Federal employees will solve the national debt. They are only 5% of the budget. Many other bigger expenditures must be addressed. Also if a workforce is to be reduced it takes an investment to move or automate the workload. And the rants of the dictator wannabee saying the work is unneeded are utter lies. Finally what on earth does spewing lies that the workers are stupid and lazy accomplish? Pure nonsense from the idiots on parade! ↩︎

- See footnote 24 above and if you still think firing federal workers while making them enemies of the state “because they don’t do anything” is true – just look at how the international bad actors from China, North Korea, and Russia just to name a few of the usual suspects – are now grinning ear to ear. Without these federal workers the thefts of funds from county, state and federal government coffers will explode without the ongoing security they provided. The security was already woefully inadequate – now it is just open season on the government coffers from the bad actors abroad. ↩︎

- What truly made the USA great in the 1940s tot he early 1970s was the largest middle class ever in the history of mankind. ↩︎

- George H. W. Bush referred to Reaganomics as “voodoo economics”. Bush muzzled his voodoo comments in exchange for being given Reagan’s Vice President job. The US debt has instead ballooned and Reaganomics should be called trickle up economics, although the concentration of US wealth has hardly been a trickle more like a roaring river. Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz wrote in 2015 that the post-World War II evidence does not support trickle-down economics. We know that Stiglitz was correct. The graphs totally disprove anything trickling down. You just can’t make this insanity up. ↩︎

- In 2007 Carlos Slim was the richest person in the world. Few however would claim that Slim’s billions displayed Mexico as an economic powerhouse. ↩︎

- PEW Research Center Report on the State of US Middle Class: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/05/31/the-state-of-the-american-middle-class/ ↩︎

- The PEW research report also says education is the primary factor determining US workers wealth (see bottom left of chart). The workers in the Information, Finance, and Professional Services industries make up a third of the upper-income tier. ↩︎