The Marxist Economic School of Thought

Marxist Perspectives on Financial Depressions

Financial depressions have long served as critical junctures for economic theory, prompting reassessment of existing frameworks and generating new analytical approaches. While mainstream economics often centers on neoclassical, Keynesian, monetarist, or Austrian school interpretations, Marxist economic theory offers a distinctive lens through which to understand these profound economic ruptures. Positioned at the extreme left of economic thought, Marxist analysis counterbalances right-leaning perspectives like the Austrian School, completing our review of the major macroeconomic models.

The Profitability Crisis Thesis: Central to Marxist Analysis

The cornerstone of Marxist interpretations of financial depressions lies in what has become known as the profitability crisis thesis. According to this framework, capitalist economies can achieve sustained recovery only when average profitability in productive sectors experiences significant improvement. This theoretical perspective derives from Marx’s original analysis of capitalism’s inherent contradictions and tendency toward crisis.

Marx argued that capitalism contains the seeds of its periodic crises and eventual demise. The competitive nature of capitalism drives businesses to continually invest in labor-saving technology to reduce costs and gain a market advantage. However, since labor is the ultimate source of surplus value in Marxist theory, this progressive replacement of human labor with machinery creates a fundamental contradiction: as businesses pursue profit maximization through technological enhancement, the collective result is downward pressure on the average rate of profit across the economy. Marx and Engels made a massive error in their calculus of labor in their philosophy. See this link for a broader explanation of Marx’s mistake (opens in a new tab).

This process leads to what Marx termed the “tendency of the rate of profit to fall.” When profitability declines below certain thresholds, capital accumulation stalls, investment contracts, and an economic crisis ensues. Recovery, in this framework, requires substantial devaluation of previously accumulated productive capital—a process later popularized by economist Joseph Schumpeter as “creative destruction.”

Profit Fell Long Before 1929

Evidence from the pre-Depression era appears to support this thesis. U.S. profitability was declining for approximately five years before the 1929 crash, with the “productivity of capital” beginning its downward trajectory from 1924 onward. This coincided with a peak in the rate of profit, suggesting that the subsequent crash was not merely a financial phenomenon but reflected deeper contradictions within the productive economy.

We can observe similar patterns in the current economic cycle. During the 1990s technology boom, numerous tech companies prioritized market share acquisition over profitability, creating unsustainable business models. This ultimately culminated in the Dot-Com implosion of 2000-2003, demonstrating how profitability crises can manifest in contemporary capitalism despite significant differences in technological and financial structures.

Financial Versus Productive Sectors: The Diversion of Capital

A critical aspect of Marxist analysis regarding the Great Depression involves the relationship between financial and productive sectors. Marxist economists observe that pre-depression economies typically experience a significant diversion of profits from productive to financial sectors—a phenomenon they interpret as capital seeking higher returns in speculative activities when productive investment opportunities become less profitable.

The statistics from the 1920s are striking in this regard. Between 1923 and 1929, financial sector profits increased by an astonishing 177%, while non-financial sectors grew by a comparatively modest 14%. This dramatic divergence indicates that capital was increasingly flowing toward speculative rather than productive investments. Further supporting this interpretation, capital gains grew twenty times faster than wages during this period, creating profound economic imbalances.

Perhaps most tellingly, speculative investments tripled while investment in new productive facilities remained largely stagnant. This pattern of over-investment in financial assets rather than productive capacity created a fundamentally unstable economic structure. From a Marxist perspective, this represents capital’s attempt to escape the profitability crisis in the productive sector by seeking returns through financial speculation—a temporary solution that ultimately exacerbates underlying contradictions.

This analysis parallels what occurred leading up to the 2000 tech crash. The excessive channeling of investment into speculative technology ventures without corresponding productive capacity or sustainable business models created a bubble that inevitably burst. In both cases, the diversion of capital from productive to financial sectors served as a harbinger of impending crisis rather than a sign of economic vitality.

The Long Recovery: Validating Marxist Predictions

One of the most compelling aspects of Marxist analysis regarding financial depressions is its explanation for their extended duration. Unlike neoclassical models that often predict relatively rapid market adjustments, Marxist theory anticipates prolonged recovery periods following major crises, particularly when addressing the fundamental profitability issues requires substantial devaluation of capital.

The Great Depression’s timeline aligns remarkably well with these expectations. By 1938—nine years after the initial crash—the U.S. corporate profit rate remained less than half its 1929 level. Even by 1940, profits had not recovered to pre-depression levels, suggesting that the economy remained caught in a profitability trap despite various policy interventions. This extended period of depressed economic activity stands as a challenge to theories predicting rapid market clearing and adjustment.

From a Marxist perspective, genuine economic recovery materialized only with the emergence of the war economy in the early 1940s. This suggests that it was not market forces but rather massive government military spending that provided the necessary monetary stimulus to overcome the crisis. This interpretation challenges conventional narratives about the efficacy of New Deal programs, arguing instead that they provided important relief but failed to address the fundamental profitability crisis at the heart of the depression.

War Economy as State Capitalism: A Temporary Solution

The transformation of the U.S. economy during World War II presents a fascinating case study for Marxist analysis. Many Marxist economists interpret the war economy as a form of state capitalism—a system where the government effectively directs economic activity while maintaining private ownership of the means of production. This arrangement temporarily resolved the profitability crisis through guaranteed government contracts, massive public spending, and direct management of production priorities.

Through rationing programs and production directives, the government contained speculative investment while ensuring private profits, effectively preventing the creation of new speculative bubbles. Companies received guaranteed returns on their investments in productive capacity, eliminating uncertainty and restoring profitability to levels that stimulated continued investment. This state-directed economy fundamentally altered the dynamics of capital accumulation, temporarily suspending some of the contradictions identified in Marxist theory.

However, Marxist analysts emphasize that this war economy was inherently temporary and sustainable only because the war had a foreseeable end. It represented an exceptional period rather than a permanent resolution of capitalism’s contradictions. This reveals a fundamental tension in Marxist theory: while it accurately identifies capitalism’s recurring struggles with profitability and investment issues, the most successful example of overcoming these issues occurred under extraordinary wartime conditions that cannot be replicated in peacetime.

This analysis leads to a sobering conclusion: the war economy’s success in restoring profitability came at the cost of massive destruction of global productive capacity through warfare, effectively achieving the “devaluation of capital” necessary for renewed accumulation through the most destructive means possible. This grim observation supports Marx’s contention that capitalism resolves its crises only by “paving the way for more extensive and more destructive crises.”

Theoretical Limitations and Historical Misapplications

Despite its explanatory power regarding certain aspects of financial depressions, Marxist economic theory faces significant challenges. Most notably, while Marxism has offered compelling critiques of capitalism’s instabilities, attempts to implement Marxist economic systems have failed to produce sustainable alternatives in complex industrial economies.

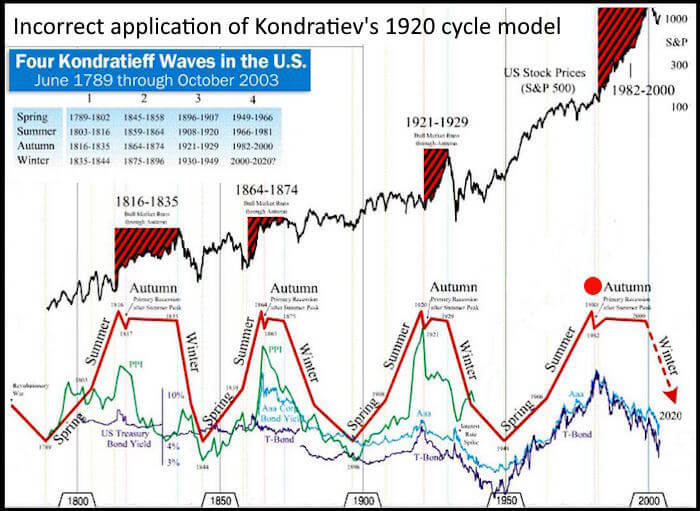

One theoretical issue involves the misapplication of economic cycle models. Some Marxist economists have utilized Nikolai Kondratiev’s long-wave theory, operating under the incorrect assumption that Kondratiev was a Marxist due to his early work in the Soviet Union. In reality, Kondratiev was not a Marxist theorist, and his economic cycle theory has been misappropriated in certain Marxist analyses.

This misapplication has led to problematic interpretations of economic history. For instance, according to Carlota Perez’s technology cycle model, the early 1970s marked the end of the fourth technology cycle. However, in misapplied Marxist interpretations of Kondratiev waves, the 1970s appear in the middle of a cycle rather than at its conclusion. This misplacement has led some Marxist economists to incorrectly conclude that the declining health of old-line industries in the 1970s represented an exhaustion of profitability across the economy rather than a natural transition between technology cycles.

Further complicating matters, these Marxist interpretations often fail to acknowledge that the United States was not a significant industrial competitor during the first and second Kondratiev cycles, making the application of these cycles to U.S. economic history before the rise of internal combustion engine technologies problematic. Additionally, some analyses erroneously combine distinct technology cycles, such as merging the third cycle (steel and electricity) with the fourth cycle (oil and gasoline engines).

Potential Model Value of Marxist Analysis

Despite these limitations, Marxist perspectives on financial depressions retain significant analytical value in contemporary economic discourse. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and subsequent recovery period have renewed interest in Marxist crisis theory, as many patterns identified by Marx and subsequent Marxist economists appeared to manifest once again.

The financialization of the economy preceding the 2008 crisis, with finance capital dramatically outpacing productive investment, echoed the patterns observed before the Great Depression. Similarly, the extended recovery period despite unprecedented monetary intervention by central banks suggests that deeper structural issues with profitability may have been at work, as Marxist theory would predict.

Moreover, the growing wealth inequality that has characterized the post-2008 recovery aligns with Marx’s description of capital accumulation dynamics, where crises ultimately lead to greater concentration of capital. The massive devaluation of assets during the crisis, followed by their acquisition at reduced prices by those with available capital, has accelerated wealth concentration in ways that seem to validate some of Marx’s criticism of capitalism.

Conclusion

Marxist perspectives on financial depressions offer valuable insights into the cyclical nature of capitalist crises, particularly regarding the profitability requirement for sustained economic growth. The analysis of the Great Depression demonstrates how financial speculation can mask underlying profitability problems until a crisis erupts, forcing a painful adjustment process that disproportionately impacts most people.

While Marxist economic theory correctly identifies significant contradictions within capitalism, it has not produced viable alternative financial systems. The ultimate value of Marxist perspectives does not lie in providing a functional alternative to capitalism. Instead, it lies in highlighting capitalism’s inherent tendencies toward crisis as a result of where an economy is relative to a technology cycle. By understanding the profitability dynamics that drive financial depressions, the factors may be of use in a technology cycle model rather than simply pointing out symptoms of the cycle’s existence.

Conclusion

Where the models are placed and what models are used matter

Marxists utilize Kondratiev’s early model because they operate under the mistaken idea that he was a Marxist since he worked as an economist in the early days of the Soviet Union. He was not. See this link for Kondratiev’s biography. As a result, some correlations were inferred that are not correct. According to Carlota Perez’s model, the end of the 4th technology cycle was the early 1970s.

In those misapplied models, the 1970s mark the middle of a Kondratiev cycle, not the end of the 4th technology cycle. Therefore, they looked at the declining health of the old-line industries and came to the fundamentally incorrect conclusion that profitability had been exhausted for industries in their prime.

A picture is worth a thousand words. The red dot in the chart below shows where the 1970s are in the Marxist-interpreted Kondratiev (AKA Kondratieff) chart. It is in the middle of the fourth Kondratieff. Aside from the relative meaning, there are some much larger issues. Since the Marxists don’t understand technology cycles in depth, they miss some important issues.

First, the US was not even in the footrace with Great Britain at the start of the Industrial Revolution. The US was not even challenging during the 2nd cycle either. Therefore, Kondratiev cycles can’t be utilized to discuss the US before the technologies centered around the internal combustion engine (the 4th cycle). And even in the chart below.1 They are using an obsolete model; they are unaware they have lumped two complete technology cycles together (cycle 3: steel & electricity with cycle 4: oil and gasoline engines). Unquestionably, they need to read the history of the evolution of the cycles at this link.

For additional background on general economic theory for the four schools you can visit wikipedia. It is not perfect but at least is not incented to be biased.

- The source for the chart is: financialsense.com/contributors/christopher-quigley/kondratieff-waves-and-the-greater-depression-of-2013-2020 ↩︎