The early technology cycle models history – Section One

Early technology cycle models

The 19th Century

It was very fashionable to think about economic cycles in the 19th century. They were acutely aware that the world was undergoing radical changes due to industrialization. However, we will spend next to no time on the 19th century. Very little utility resulted from that work. That thinking subsequently went into the dustbin of history. Make no mistake, several well-known individuals proposed ideas. William Jevons, the economist who came up with the concept of marginal utility, proposed a linkage between sunspot cycles and economic activity. Another notable pair of individuals was Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. They developed the fallacious philosophy of communism, but they were among the first to study the impact of technology on capitalist economies.

To understand what they did and where they erred, please visit this link. The general history of technology cycles now quickly moves on to the people and ideas that contributed to the ultimate construction of usable technology cycle models.

The early days

The early technology cycle models developed in the 1920s was a dramatic episode in the historical development of economics. A Norwegian economist Jens Andvig divided technology cycle research in the 1920s into two competing disciplines. The first was cored in data structures and were therefore empiricists in their approach. Examples included the Harvard Business Barometer, Wesley Mitchell’s creation of the National Bureau of Economic Research (N.B.E.R.), John Babson’s Business Barometer, and Nikolai Kondratiev’s Institute of Conjecture. These groups took an empiricist approach in revealing how the business cycle as a whole operated. The second group thought about cycles from a totally theoretical approach. They were divided among a number of competing schools as well. The more famous examples are: the Cambridge school of John Maynard Keynes and Dennis Robertson. As well the Austrian school of Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek to name two famous examples.

The Conjecture Institute in Moscow sprang to life in the 1920s just a few short years after the Soviet Union began. The Conjecture Institute is a name very few have heard of. The Institute would be dissolved in 1928. Stalin would sweep away anyone who could have been even remotely interpreted as having stood in the way of his farm collectivization plan. It was one of the few times in human history where economists could be executed for academic thinking. Ironically it was the director of the Conjecture Institute who would make the most headway on the great technology surges. Kondratiev’s name would become synonymous for what he termed the long cycles despite his having to pay the ultimate price for his work.

Father of Long Cycles Nikolai Dmitriyevich Kondratiev (Никола́й Дми́триевич Кондра́тьев )

The history of the Great Technology Surges (long cycles) began in earnest with Nikolai Kondratiev. Since the name is translated from Russian he has also been referenced under several surnames. Kondratieff, Kontradieff, Kondratyev, and Kondratev are just a few examples. After the Bolshevik party seized power in November of 1917 a civil war ensued. It was called the War Communism.

Accordingly in 1920 Kondratiev was named Director of the newly created Institute of Conjecture. A vast economic crisis had enveloped the newly formed USSR. Due to the fear of the Bolsheviks from being attacked by European governments, they had suspended all trade with Europe. The result was enormous economic damage. The nascent USSR government was searching for a way to quell the rising unrest in the country. They adopted a pro-market approach to blunt the economic disaster they had fostered. Lenin was even leaning towards cooperatives. Kondratiev was seeking a path to a policy in reopening trade with Europe to enable trade cooperatives while industrializing Russia.1

Kondratiev was seeking trade because he was of the opinion that investing in Russian farming while allowing the farmers to reap financial rewards for their work would accelerate the USSR’s GNP and speed up industrialization. This point of view would get him executed later as after Lenin died; Stalin and the Bolsheviks who all fell in line with the dictator, favored collectivization of the Russian farms instead of cooperatives. Not covered here but Stalin’s brutality and decision to collectivize USSR farms was why the USSR subsequently confiscated all of the Ukrainian farming output creating the starvation of millions in 1932 and 1933 (Holodomor – opens in new tab).

Kondratiev’s early technology cycle models

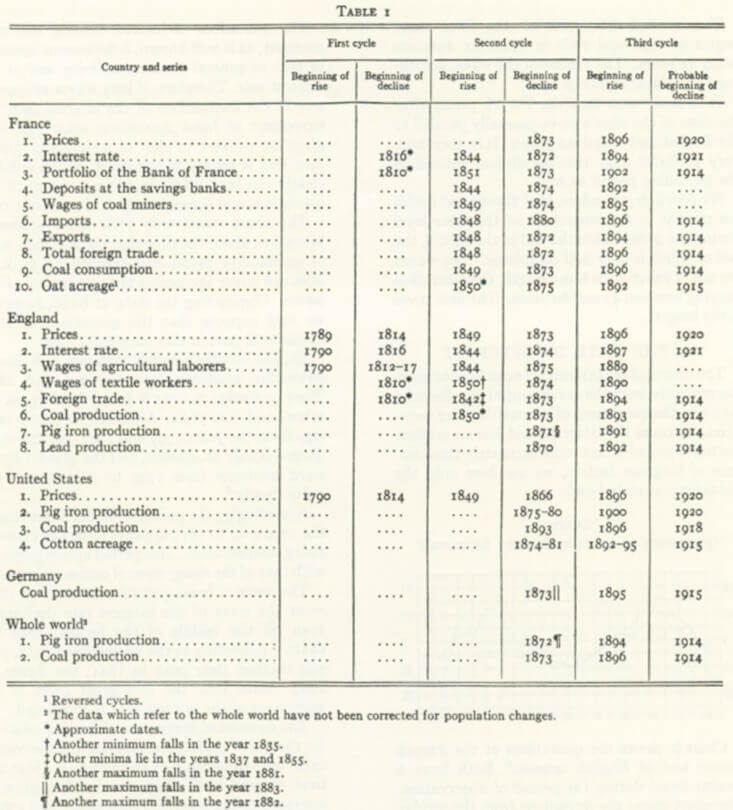

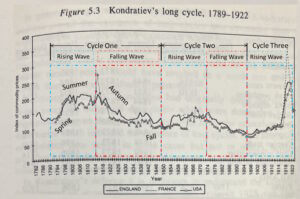

During the 1920s Kondratiev began research in earnest for the early technology cycle models. He did so by looking at historical data for UK grain market prices, interest rates and farm labor wages. The data started from the 1780s and ended in the early 1920s. He did this because that is all the data he would ever have. Kondratiev did look at the US and France as well as other metrics but the only complete data set he had was for the three sets from England. He did project the end of the cycle they were experiencing as the 1920s. He did this because he surmised from the little data he had that the cycles he termed Long Cycles ran about 45 to 60 years in length from start to finish and would therefore conclude in the 1920s.

The real data – not what is found on the Internet

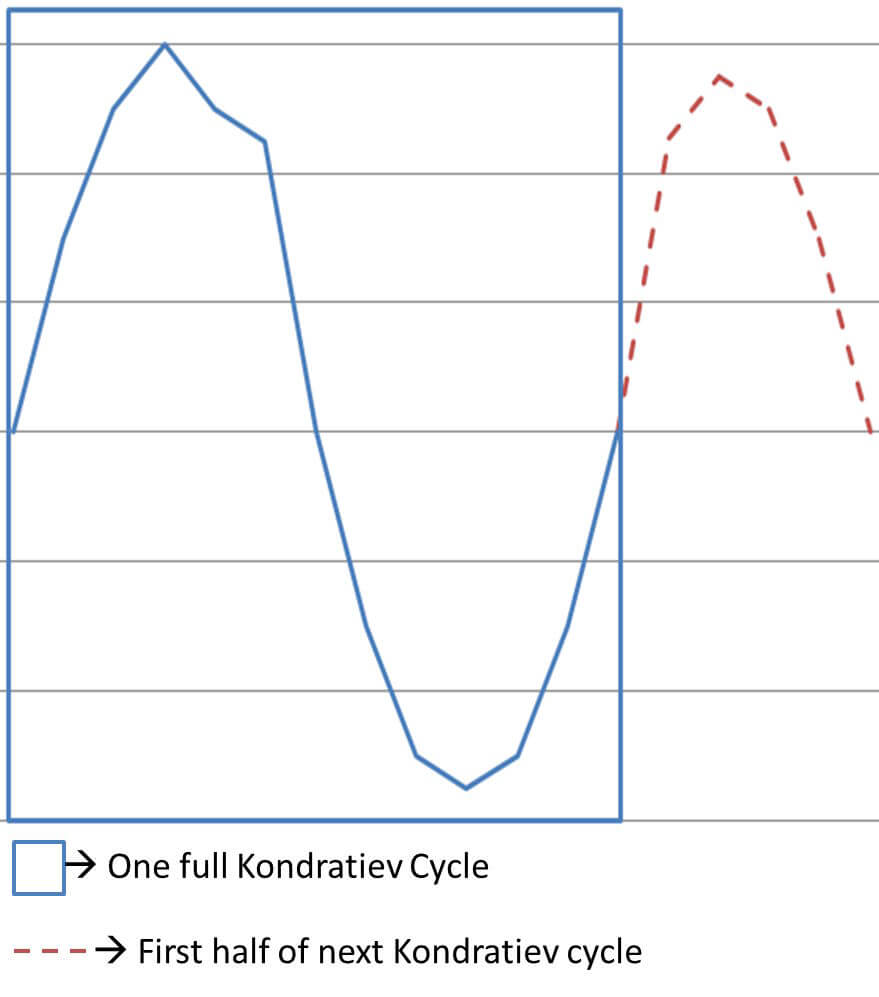

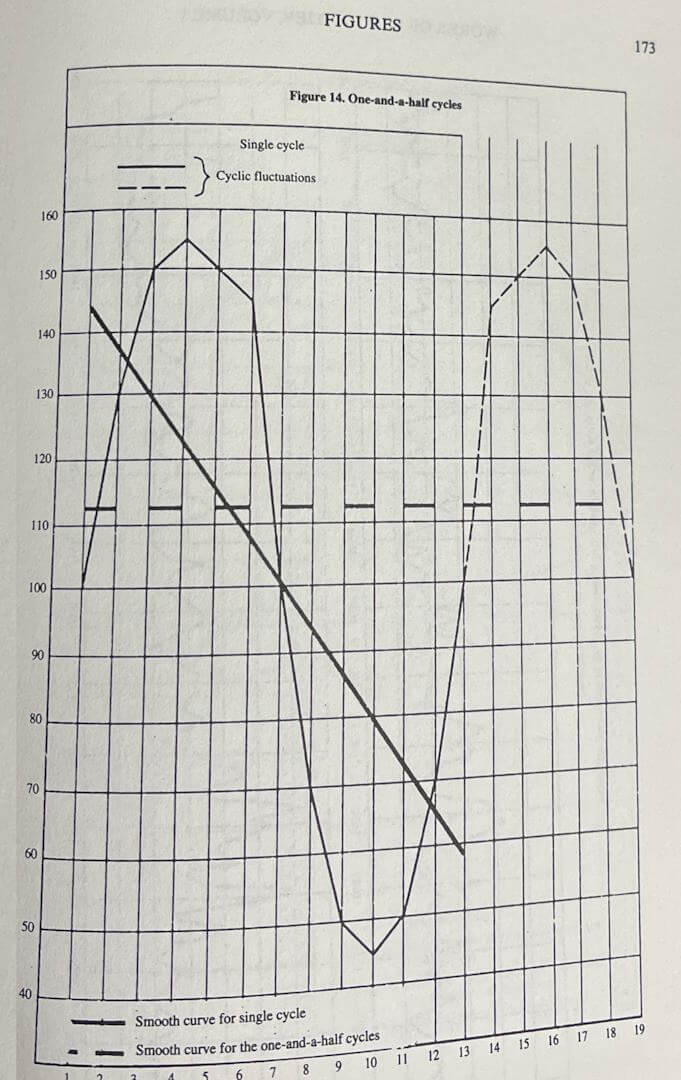

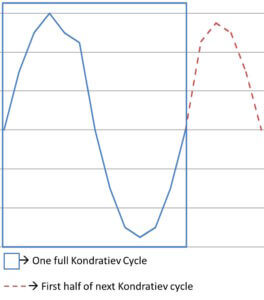

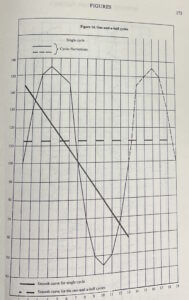

In the images below you will see two things. On the left an image of the table Kondratiev’s published from the lone translated 1926 article published outside of Russia during his lifetime. The image in the middle is the one and only graph Kondratiev ever created showing what he thought a technology long cycle looks like. This graph was found in a trunk by his daughter and would only be published in the 1998.2 No embellishments just what little data he had and what he actually thought.

I include this immediately below to demonstrate just how much misinformation has been generated that is not factual. Next to his graph is a photo of this same graph. I had redrawn it on the left as the photo is difficult to read. If you google a “Kondratiev cycle” every single result and image as well as the vast majority of the words are all wrong including Wikipedia’s (first link which comes up). I have even seen some articles claiming he published a book in 1925! Will attempt to correct the errors as we move through the history.3

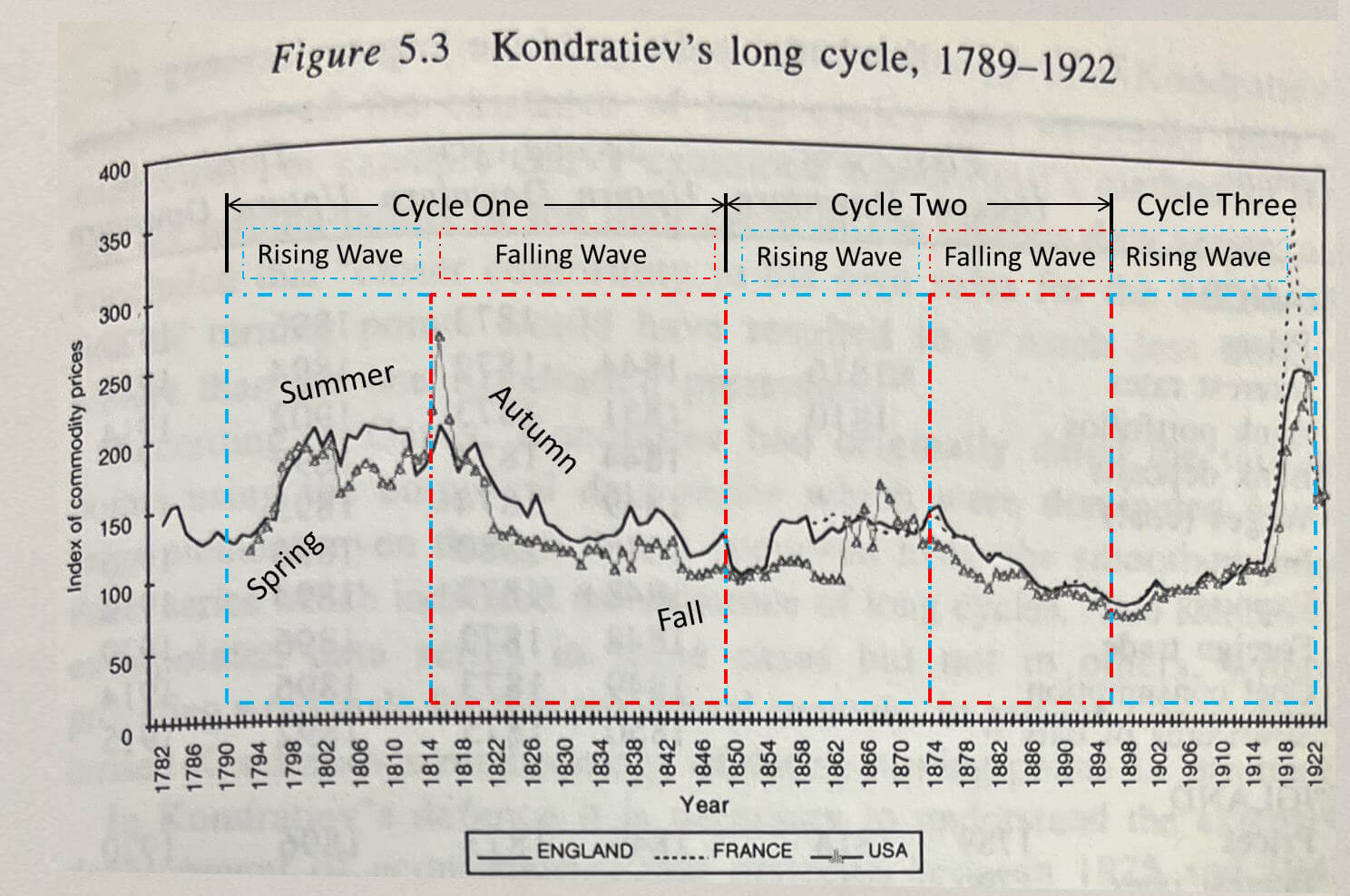

Kondratiev’s technology cycle research papers

On the far right (above) is the chart where Kondratiev graphed commodity prices as a proxy measurement for long cycles. He put this chart in the 1925 paper he wrote devoted to his long cycle theory. To aid in digesting his chart I have added the cycle numbers, season definitions along with the red and blue lines denoting the rising and falling waves inside the cycle. This paper would be reduced and published in German academic periodical. The article would further be reduced and republished in English in 1935.44 See the Kondratiev section on theory to see the five graphs which were actually published in English. None of them look like what is found within the misinformation on the Internet.

It is a mistranslation from Russian which stated he called the technology driven cycles – long waves. What Kondratiev did say was that each cycle was made up of two distinct waves. The first wave was rising followed by a second falling wave. The rise and fall of the two waves constitutes one complete long cycle. He was adamant about these terms. Nikolai grew up in an agricultural world and this is why he likely named the rising waves segments spring and summer and falling wave autumn and fall. The seasons determined everything for farmers. Not as much for the industrial economy. Because Kondratiev wrote in Russian and everything had to be translated, sometimes multiple times, errors brought about the incorrect name for long cycles. This error continues to this day. Ironic isn’t it? That the longest economic cycles are suffering from repetitively being called by the incorrect name.

Kondratiev’s contributions

Because he measured the major crashes, he correctly projected the number of cycles. That was no small feat as he had only lived through two cycles! However, he put the crashes both at the end and the beginning for each cycle. Carlota Perez would fix this later at the end of the 20th century (more on her brilliance in section three). He made this mistake because he was working before economists ever calculated things like Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or other meaningful measurements. He was also measuring agriculture indices as there were no industrial measurements to speak of yet.

In 1976, a British statistician named George Box wrote the famous line, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” His point was that the focus should be on whether something can be applied to everyday life in a useful manner rather than debating endlessly if an answer is correct in all cases. The history and theory of the great technology surges will ultimately fall into Box’s definition of a model which will become very useful after some fits and starts.

Kondratiev’s final contribution was that he introduced scientific rigor to macroeconomics, a field that had previously lacked it. His projections were based on painstaking statistics and research, under unimaginable conditions, no less. His data would fire the imaginations of the next set of economists in the history of technology cycles. Section two, clarity begins to surface for the impacts of innovation and techno-economics.

Footnotes Follow:

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development, Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Author Vincent Barnett. Pages 47 – 48. ↩︎

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Page xxxiii. ↩︎

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Pages 37 image left & right image page 173. ↩︎

- W.F. Stolper of Harvard University for The Review of Economic Statistics (Vol XVII, No. 6) Nov 1935. ↩︎