Nikolai Kondratiev’s Biography

Nikolai Kondratiev’s Biography

Also known as: Kondratieff, Kontradieff, Kondratyev, and Kondratev.

1892

Nikolai Dmitrievich Kondratiev, also known as Kondratieff, Kontradieff, Kondratyev, and Kondratev, was born on March 17, 1892, in Galuevskaya village, Kostroma Guberniya, to a poor peasant family. Despite limited educational resources for low-income children—mainly church and teachers’ schools—he pursued learning with determination.1

1905

Early in life, he joined the Socialist-Revolutionary Party and actively engaged in democratic protests. Authorities arrested him twice, in 1905 and 1906.

1915

Because poverty barred him from attending elite secondary schools, Kondratiev chose an alternative route. He independently passed all required exams and subsequently enrolled in the juridical faculty at St. Petersburg (Petrograd) University, where he graduated in 1915. While studying, he published his first article in 1914, titled The Central Doctrines of the Social Development Laws. The following year, he released an in-depth analysis of the economy of Kinishma district in Kostroma.

Simultaneously, he educated workers, believing that economic literacy would empower the working class. He also participated in anti-monarchist demonstrations, which eventually led to his arrest during the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. Although mentors encouraged him to pursue an academic career after graduation, Kondratiev decided to combine research with public service. He joined the economic section of the Petrograd Union of Zemstvos during World War I, where he helped support wounded soldiers.

As revolutionary tensions rose in Russia, Kondratiev focused on macroeconomic and agrarian issues. After the Czar abdicated and the Russian Provisional Government took power, Kondratiev took on several key roles: Vice-Chairman of the State Food Committee, member of the Commission on Agrarian Reform, and participant in the Central Land Committee.

1917

In December 1917, the Kostroma region elected Kondratiev to the Constituent Assembly (Duma). Although he refrained from strongly protesting its dissolution in January 1918, he harshly criticized Bolshevik policies, particularly those contributing to famine and economic chaos. By early 1918, he had relocated to Moscow.2

1920

In 1920, Kondratiev founded and led the Conjuncture Institute—the USSR’s first scientific body to analyze economic cycles. He emphasized economic theory while addressing practical policy concerns. As a result, economists such as John Maynard Keynes, Wesley Mitchell, and Irving Fisher recognized his work. Several respected institutions—including the American Economic Association and the Royal Economic Society—welcomed him as a member.3

1922

Although the early 1920s brought stability, political tensions persisted. In 1922, the government arrested Kondratiev for alleged counter-revolutionary activities and temporarily imprisoned him. Still undeterred, he traveled abroad in 1924–1925 to study agricultural systems in the U.S., Canada, Britain, and Germany. He corresponded with Wesley Mitchell and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), where Mitchell encouraged him to publish internationally. Mitchell also wrote to him: “I hope heartily that you will take every opportunity to publish in English, French, or German, so that not only I but many others may profit by your contribution.”4

1924

Although the USSR launched its first five-year plan around that time, Kondratiev publicly challenged its implementation, not its goals. Critics coined the term kondratievshchina to mock his position, associating it with capitalist tendencies. Nonetheless, he held firmly to his vision for balanced economic development. The timing could not have been worse, as Kondratiev traveled to the west at this time.

1926

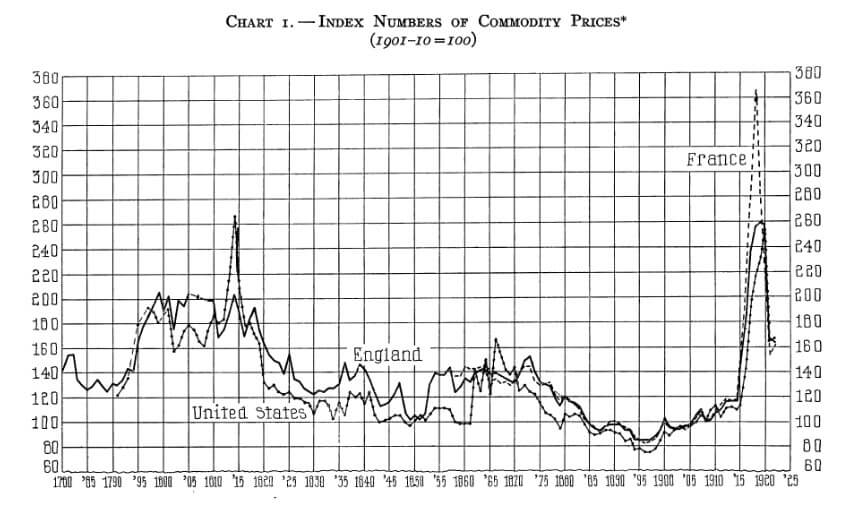

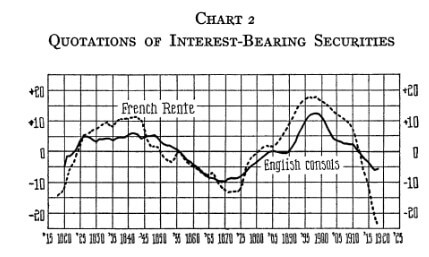

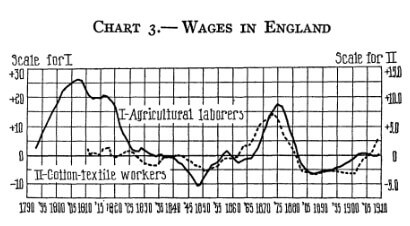

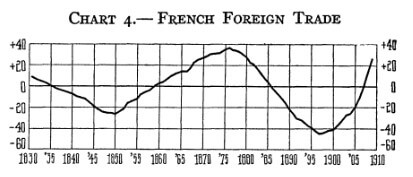

In 1926, Kondratiev presented his groundbreaking theory on long economic cycles in a report titled Long Cycles of Conjuncture. He introduced this theory at the Institute of Economics, sparking interest and backlash. This work would later be translated into English in a heavily abridged form in 1935 by W.F. Stolper of Harvard University. That article would then be translated into English. It was a heavily abridged article by W.F. Stolper of Harvard University for The Review of Economic Statistics (Vol XVII, No. 6, Nov 1935).5 Kondratiev’s only paper devoted to Long Cycles would eventually be published in English. This occurred only with this one instance during his lifetime. “During his lifetime, Kondratiev saw only one of his papers on Long Cycles published in English. This occurred when a 1926 German article of his, originally published in the academic periodical: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik, was translated.”6

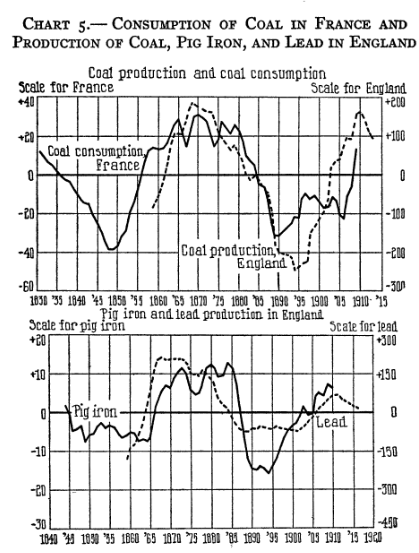

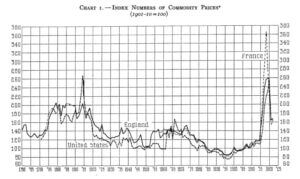

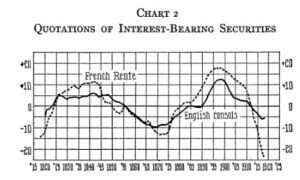

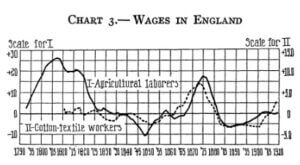

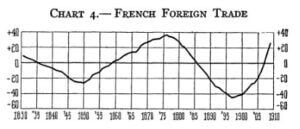

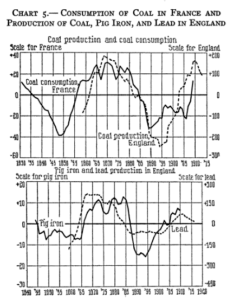

Kondratiev published only five graphs outside of Russia during his lifetime, all in his lone 1926 article. Translators eventually published all of his writings in English in 1998. Yet, almost no one discussing Long Waves today has actually read that work, despite its brilliance. When I researched his original words, I discovered that only the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business (Lippincott Library) holds the complete four-volume set of his works published in 1998. Even the Library of Congress doesn’t have it! No wonder misinformation keeps circulating.

1927

In 1927, a more intense discussion arose. This pertained to the five-year economic plan. It had a significant impact on Kondratiev’s life, as well as on the entire planning process in the USSR. He stressed that a balanced economy was an integral part of stable development. As applied to the primary objective of the period industrialization, it meant the necessity to coordinate industrial development with progress in agriculture.

Although Kondratiev’s theory gained attention, his outspoken critiques of the five-year plan further alienated Soviet authorities. He insisted that successful industrialization required a balance with agricultural development. To achieve this, he advocated for allowing peasants to benefit economically and for developing a consumer goods sector to integrate them into the market.

During this time, Kondratiev voiced these views through numerous articles and speeches. However, the political climate turned sharply against him in late 1927. G. Zinoviev, a senior Bolshevik leader, published a damning critique in the journal Bolshevik, branding Kondratiev and his colleagues as ideological enemies. Authorities accused him of siding with the kulaks, resisting collectivization, and even enabling capitalism.

1926-27

In 1926–27, Kondratiev defended these ideas through several articles, speeches, reports, and papers directed to higher authorities. In November 1927, G. Zinoviev—famously portrayed in the movie Reds, and a prominent political and party figure who served on the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party from 1902 to 1926—published an article in the journal Bolshevik. He delivered political and ideological criticisms of Kondratiev’s position and those who supported him. In many ways, this article shaped the tone and direction of future attacks against Kondratiev and numerous others. Critics branded Kondratiev’s views as ‘the manifesto of the kulak party’ and labeled him—and many scholars and specialists—as ‘liberal’ and, at times, with even harsher terms.

Kondratiev’s critics primarily attacked his views on planning and regulation, his agricultural policies, and his theory of long cycles. They accused him of opposing industrialization and collectivization, standing against the poorest peasants, and supporting the kulaks and the restoration of capitalism. Even more damning, politically, they condemned him for stating that it was impossible to predict the exact date of capitalism’s collapse.

NBER collaboration

Until he was arrested in 1928, he would exchange economic data with the NBER, which some think was why he lived for another 10 years in prison before being executed. He was a highly renowned economist in the West during the 1920s, and he was the primary source of economic data for the Soviet Union. Some think that is why he was locked away from 1928 to 1938. His silence would, in effect, get the West to forget about him and his ideas.

1928

In 1928 Kondratiev was dismissed from his post as Director of the Conjuncture Institute, and the latter ceased to exist. In July 1930 he was arrested. Kondratiev’s interrogator, Agranov was ‘one of the most feared Sadists in the Lubyanka prison’.7 Stalin took a keen personal interest in the arrest and trial proceedings relating to Kondratiev. In a letter to V.M. Molotov dated 2 August 1930; Stalin recommended that the testimonies of Kondratiev … should be sent to all the members of the Central Committee, calling them ‘documents of primary importance’.

A few days later, Stalin wrote of the “government” of Kondratiev-Groman’, and urged that the investigation into Kondratiev must be continued ‘very thoroughly and without haste’. Stalin also wrote in a letter to Molotov that it was now clear that the execution of Kondratiev, Yurovskii, and other leading ‘economist-scoundrels’ was necessary. Given such an attitude from Stalin, it is somewhat surprising that Kondratiev survived for as long as he did after his arrest.8

1932

In January 1932, the closed trial in connection with the prosecution of the so-called ‘Labor-peasant Party’ took place, following the trials of the members of the ‘Industrial Party’ and ‘Menshevik-counter-revolutionaries’. Kondratiev was found guilty of sabotage in agriculture and the implementation of bourgeois methods in planning, and was soon a prisoner at Suzdal prison, near Vladimir. Kondratiev was sentenced to eight years of solitary confinement.

Although in prison, Kondratiev continued to develop his work on long cycles. He did complete a volume on trends, but the fate of the manuscript is unknown. The book on methodology, ‘The Basic Problems of Economic Statics and Dynamics’, was saved but unfinished.

1936

By 1936, Kondratiev’s health deteriorated severely. Blindness and isolation robbed him of his final lifeline to the world. On September 17, 1938, the Military Board of the Supreme Court found him guilty of anti-Soviet activity and executed him that same day.

1956 & 1987

In later decades, Soviet leaders posthumously rehabilitated Kondratiev. First, during Khrushchev’s Thaw in 1956, the government repealed his 1938 sentence. Then, in 1987, Glasnost policies led to the reversal of his 1932 conviction. His wife, Evgeniya Dorf, and daughter, Elena, preserved his manuscripts and played a crucial role in publishing his complete works. Thanks to their dedication, Routledge published The Works of Nikolai D. Kondratiev in a four-volume set in 1998.

This was a summary of Nikolai Kondratiev’s biography. Let’s now move on to his theory and why the world continues to remember this economist to this day –> Kondratiev-Theory-Influence/

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Page xxvii. ↩︎

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Page xxviii. ↩︎

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Page xxix. ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development, Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Author Vincent Barnett. Page 75. ↩︎

- The Review of Economics and Statistics (RESTAT) continues to be published. It covers applied economics and especially quantitative economics. It is edited at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government. ↩︎

- In 1933, when the Nazis gained power in Germany, the last editor of the Archive and half of the editorial staff of the journal were forced to emigrate and the journal ceased to exist. ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development, Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Author Vincent Barnett. Page 191. ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development, Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Author Vincent Barnett. Page 194. ↩︎