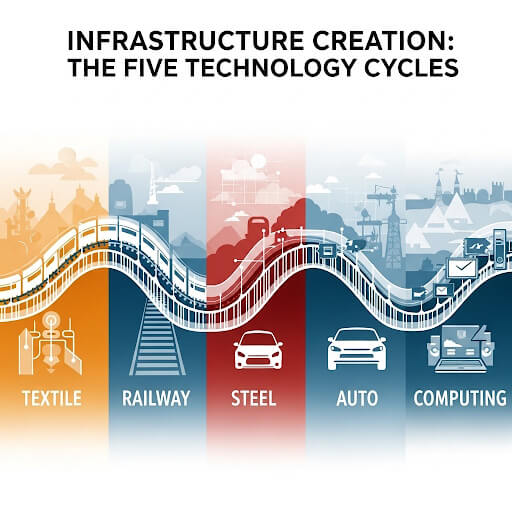

Infrastructure Creation

The Infrastructure Creation Across Five Technological Revolutions:

Infrastructure systems create the invisible foundation that enables technological revolutions to transform entire societies. Throughout history, each technological revolution has successfully navigated from the chaos of its Installation Period through the crisis of its Turning Point to emerge into the productive Deployment Period. However, our current fifth technology cycle—the Information Age—presents an unprecedented challenge: we remain trapped in an extended Turning Point, unable to complete the critical infrastructure creation that would enable our transition to the Deployment Period.

This extended crisis represents more than a temporary economic disruption. Unlike the four previous technology cycles that successfully created comprehensive enabling systems during their Installation Periods, the digital revolution has struggled to establish the fundamental infrastructure required for broad societal integration. While we have witnessed remarkable technological advancement in computing, telecommunications, and digital platforms, we have failed to create the regulatory frameworks, institutional coordination mechanisms, and social infrastructure necessary to harness these technologies for widespread prosperity and stability.

Understanding why we remain stuck requires examining how infrastructure creation succeeded in previous cycles and identifying the unique challenges that distinguish our current predicament. The progression from Arkwright’s water-powered mills to Ford’s assembly lines reveals a consistent pattern: each revolution created comprehensive enabling systems that coordinated technical innovation with social organization, regulatory frameworks, and economic institutions. Our digital revolution, despite its technical sophistication, has not achieved this systematic integration.

The Pattern of Successful Infrastructure Creation in Previous Cycles

The Textile Revolution: Establishing Industrial Infrastructure Foundations

(1771-1829)

Richard Arkwright’s water frame represented more than a technological breakthrough—it established the first systematic industrial infrastructure that would define manufacturing organization for centuries. The Cromford mill created comprehensive enabling systems that integrated production facilities, worker housing, transportation networks, and social services within coordinated communities. This infrastructure achievement enabled the textile revolution to move successfully through its Turning Point crisis (1793-1797) into a productive Deployment Period.

Arkwright’s infrastructure innovation extended beyond factory organization to create systematic approaches to technology transfer and commercial scaling. His patent licensing system enabled mill construction across Britain, Scotland, and eventually Germany and America, demonstrating how intellectual property frameworks could facilitate rather than hinder technological diffusion when properly structured. The licensing approach created enabling infrastructure for rapid geographic expansion while maintaining quality standards and operational coordination.

The temporal infrastructure established by textile mills proved equally revolutionary. Bell systems at 5 AM and 5 PM created the first systematic industrial time management, replacing agricultural rhythms with mechanical precision. This temporal coordination system became fundamental to all subsequent industrial organization, enabling complex production scheduling and worker coordination that supported the transition from Installation Period chaos to Deployment Period stability.

Most critically, textile infrastructure created comprehensive mill towns that demonstrated how technological systems require supporting social infrastructure to achieve full operational potential. The systematic organization of work schedules, housing arrangements, and community services established templates for industrial community development that enabled social adaptation to technological change while maintaining community cohesion and democratic participation.

The Railway Revolution: Systematic Engineering and National Integration

(1829-1873)

Stephenson’s Rocket locomotive launched a transportation revolution that required unprecedented systematic engineering and institutional coordination. The Liverpool-Manchester Railway demonstrated how complex technological systems demand comprehensive advance planning that considers technical, economic, and social integration requirements simultaneously. This systematic approach enabled the railway revolution to navigate its brief Turning Point crisis (1848-1850) and enter a highly productive Deployment Period.

Railway infrastructure achieved the first systematic technical standardization across organizational boundaries. The 4 ft 8½ in gauge became Britain’s national standard, eventually spreading globally and demonstrating how early infrastructure decisions create persistent path dependencies. This standardization enabled interoperability while maintaining competitive dynamics among railway companies, creating enabling infrastructure that supported both coordination and innovation.

The temporal coordination requirements of railway operations demanded systematic institutional innovation that exceeded previous organizational capabilities. Railway time replaced local time variations, creating synchronized national timekeeping that enabled complex scheduling and operational coordination. This temporal infrastructure facilitated economic integration across entire regions and nations while establishing coordination mechanisms that would prove essential for subsequent technological revolutions.

Railway development established comprehensive regulatory frameworks that addressed public safety, economic coordination, and service quality through systematic government oversight. The Railway Acts created institutional templates for managing complex technological systems while maintaining private ownership and competitive innovation. These regulatory innovations provided enabling infrastructure for democratic governance of technological systems that would prove essential for managing subsequent technological revolutions.

The network effects created by railway infrastructure demonstrated how enabling systems generate increasing returns that justify continued investment and expansion. Each additional railway connection increased system value for existing users while creating economic incentives for further network development. This infrastructure dynamic enabled the railway revolution to achieve comprehensive geographic coverage and economic integration that supported successful transition to the Deployment Period.

The Steel Revolution: Material Standards and Global Coordination

(1875-1918)

Carnegie’s steel revolution established systematic approaches to material science and quality control that enabled predictable engineering performance across diverse applications. The Bessemer process and open hearth furnaces created mass production capabilities that reduced steel costs while improving quality and consistency. This material infrastructure enabled the steel revolution to navigate its Turning Point crisis (1893-1895) and enter a Deployment Period that transformed construction, transportation, and manufacturing.

Steel infrastructure development required vertical integration systems that coordinated mining, transportation, processing, and manufacturing within comprehensive supply chains. Carnegie’s control of iron ore mines, coke production, shipping, and steel manufacturing demonstrated how complex technological systems benefit from systematic integration rather than market coordination alone. This integrated infrastructure approach enabled cost reduction and quality control that supported broad economic adoption.

The establishment of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) created systematic approaches to technical standards development that enabled global coordination while maintaining competitive innovation. These material standards facilitated international trade while ensuring engineering performance and safety requirements. The standards infrastructure demonstrated how professional organizations could coordinate technical development across competitive firms while maintaining innovation incentives.

Steel applications in construction transformed architectural and engineering possibilities by enabling skyscraper construction, long-span bridges, and complex machinery that exceeded previous structural capabilities. Steel infrastructure demonstrated how material innovations create enabling platforms that support diverse technological applications across multiple industries. This platform characteristic enabled steel technology to support broad economic transformation during the Deployment Period.

The global diffusion of steel technology created international economic relationships that influenced trade patterns and diplomatic cooperation. Steel infrastructure development established systematic approaches to international technology transfer that enabled global industrial development while maintaining competitive dynamics. This international coordination capability proved essential for managing the complex global integration that characterized the steel revolution’s Deployment Period.

The Automotive Revolution: Mass Production and Social Transformation

(1908-1974)

Ford’s moving assembly line revolutionized manufacturing by creating systematic production coordination that optimized resource utilization while achieving unprecedented scale and cost reduction. The Highland Park plant reduced Model T assembly time from 12.5 hours to 93 minutes, demonstrating how systematic production design could achieve dramatic efficiency improvements. This production infrastructure enabled the automotive revolution to navigate its extended Turning Point crisis (1929-1943) and enter the most successful Deployment Period in modern history.

The assembly line required comprehensive worker coordination systems that synchronized human activity with mechanical production rhythms. Ford’s $5 day policy addressed worker retention challenges while creating systematic approaches to labor management that balanced productivity requirements with employee welfare considerations. This social infrastructure innovation enabled mass production while maintaining worker cooperation and social stability.

Automotive infrastructure demanded comprehensive supporting systems including highway networks, gasoline distribution, repair services, and financing mechanisms that created integrated mobility ecosystems. These supporting systems required coordination among government agencies, private companies, and individual users on an unprecedented scale. The systematic development of this infrastructure enabled automotive technology to achieve broad social adoption and economic integration.

Mass production techniques enabled affordable access to complex technological products while creating consumer markets that supported continued technological development and economic growth. The Model T’s price reduction from $850 to $260 demonstrated how systematic production optimization could democratize access to advanced technology. This affordability infrastructure enabled mass market development that supported the automotive revolution’s successful Deployment Period.

The comprehensive transformation of urban form and social organization created new patterns of residential, commercial, and industrial development that established social arrangements persisting despite subsequent technological changes. Suburban communities, shopping centers, and automobile-oriented infrastructure created social infrastructure that enabled new forms of economic activity and community organization while maintaining democratic participation and social cohesion.

The Digital Revolution’s Infrastructure Failure: Why We Remain Stuck

The Unique Challenges of Digital Infrastructure Creation

The digital revolution presents unprecedented challenges for infrastructure creation that distinguish it fundamentally from previous technological revolutions. Unlike physical infrastructure systems that operate according to material constraints and geographic limitations, digital infrastructure operates through algorithmic coordination mechanisms that can change rapidly and globally while creating new forms of complexity and interdependence.

Digital platforms demonstrate how infrastructure systems can coordinate millions of independent participants through algorithmic mechanisms while maintaining system performance, security, and compatibility. Operating systems, cloud computing, and application programming interfaces create layered coordination systems that enable rapid innovation while preserving systematic integration. However, this technical sophistication has not translated into the comprehensive social and institutional infrastructure required for successful transition to the Deployment Period.

The speed of digital infrastructure change creates temporal mismatches between technological development and institutional adaptation capabilities. Traditional regulatory frameworks developed for managing railway and steel infrastructure operated on decadal planning horizons, while digital infrastructure undergoes fundamental transformation within years or even months. This acceleration creates governance challenges that exceed existing institutional capabilities while requiring new approaches to democratic oversight and social coordination.

Digital infrastructure creates network effects and path dependencies that operate at unprecedented speed and global scope, creating switching costs and competitive dynamics that require careful regulatory oversight to maintain competitive markets and democratic accountability. The concentration of digital platform control within limited organizations creates systematic risks for democratic governance while requiring institutional innovations that have not yet been successfully implemented.

The Regulatory Infrastructure Gap

Unlike previous technological revolutions that successfully established comprehensive regulatory frameworks during their Installation Periods, the digital revolution has failed to create effective governance mechanisms for managing platform coordination, data privacy protection, and algorithmic accountability while maintaining innovation incentives and democratic governance.

The global scope of digital platforms creates jurisdictional challenges that exceed traditional regulatory capabilities while requiring international cooperation mechanisms that have not been successfully developed. Digital governance represents the current frontier of institutional innovation, but progress has been insufficient to enable transition from the Turning Point to the Deployment Period.

Cybersecurity frameworks, data protection regulations, and identity management systems represent attempts to create institutional capabilities for managing digital risks while preserving innovation opportunities. However, these regulatory efforts have not achieved the systematic coordination and democratic legitimacy that characterized successful infrastructure creation in previous technological revolutions.

The challenge of translating technical complexity into accessible public discourse while enabling meaningful citizen engagement with infrastructure decisions has not been successfully addressed. Digital infrastructure governance requires democratic participation mechanisms that can manage technical complexity while maintaining public accountability, but such mechanisms have not been effectively developed.

The Social Infrastructure Deficit

Digital infrastructure has failed to create the comprehensive social coordination mechanisms that enabled previous technological revolutions to achieve broad societal integration and democratic participation. While digital platforms enable global communication and coordination, they have not established the community-level social infrastructure that supported successful technological adoption in previous cycles.

The digital divide represents a fundamental failure to create universal access infrastructure that would enable broad participation in digital economic opportunities. Unlike previous technological revolutions that achieved comprehensive geographic coverage through systematic infrastructure development, digital technology has created persistent access barriers that prevent full social integration.

Digital platforms have created new forms of social fragmentation and political polarization rather than the social cohesion that characterized successful technological revolutions. The algorithmic coordination mechanisms that enable technical efficiency have not created the shared experiences and common standards that bind communities together while providing foundations for democratic participation and social solidarity.

The digital haves and have-nots have led to a systematic digital literacy and education infrastructure that has prevented a broad public understanding of digital systems and their social implications. This educational deficit undermines democratic participation in digital infrastructure decisions while weakening social support for necessary investments and institutional innovations.

The Economic Infrastructure Stalemate

Digital infrastructure has created unprecedented economic concentration while failing to establish the broad-based prosperity mechanisms that characterized successful technological revolutions. Unlike previous cycles that created comprehensive employment opportunities and economic mobility through systematic infrastructure development, digital technology has generated wealth concentration that undermines social stability and democratic governance.

The gig economy represents a failure to create systematic labor infrastructure that would provide economic security and social benefits comparable to previous technological revolutions. Digital platforms have created new forms of economic activity without establishing the institutional frameworks necessary to ensure worker welfare and social protection.

Digital infrastructure has not created the comprehensive financing mechanisms that would enable broad access to digital economic opportunities. Unlike previous technological revolutions that established systematic approaches to consumer financing and business development, digital technology has created barriers to economic participation that prevent full social integration.

The failure to establish systematic approaches to digital taxation and revenue distribution has prevented governments from capturing sufficient resources to fund necessary social infrastructure and public services. This fiscal deficit undermines the public investment capabilities that proved essential for successful infrastructure creation in previous technological revolutions.

Comparative Analysis: Why Previous Cycles Succeeded Where We Have Failed

Systematic Integration vs. Technical Optimization

Previous technological revolutions succeeded because they created comprehensive integration between technical innovation and social organization, regulatory frameworks, and economic institutions. Each successful cycle established enabling systems that coordinated technical capabilities with democratic governance and social welfare while maintaining innovation incentives and competitive dynamics.

The digital revolution has achieved remarkable technical optimization while failing to create systematic social integration. Digital platforms demonstrate unprecedented technical sophistication in algorithmic coordination and global connectivity, but these technical achievements have not translated into the comprehensive social infrastructure that would enable successful transition to the Deployment Period.

Previous cycles created infrastructure that served broad social purposes while generating private profits and competitive innovation. Railway infrastructure enabled national economic integration while maintaining competitive railway companies. Steel infrastructure enabled construction and manufacturing advancement while preserving competitive steel producers. Digital infrastructure has not achieved this balance between social benefit and competitive innovation.

The systematic approach that characterized successful infrastructure creation in previous cycles required long-term thinking that considered environmental sustainability, social equity, and democratic governance alongside technical performance and economic efficiency. Digital infrastructure development has prioritized technical performance and economic returns while neglecting the comprehensive social considerations that proved essential for successful technological integration.

Democratic Participation vs. Technical Expertise

Previous technological revolutions successfully balanced technical expertise with democratic participation through institutional innovations that enabled informed public engagement with complex technical issues while maintaining technical effectiveness and innovation capabilities. Railway regulation, steel standards development, and automotive safety oversight demonstrated how democratic institutions could govern complex technological systems while preserving competitive innovation.

Digital infrastructure governance has failed to create effective mechanisms for democratic participation in technical decision-making while maintaining system performance and innovation capabilities. The technical complexity of digital systems has been used to justify technocratic governance approaches that exclude democratic participation rather than creating institutional innovations that enable informed public engagement.

The concentration of digital platform control within limited organizations has created systematic challenges for democratic accountability that exceed the governance challenges faced by previous technological revolutions. Unlike railway companies or steel producers that operated within clear regulatory frameworks and competitive markets, digital platforms operate as quasi-governmental institutions without effective democratic oversight.

The global scope of digital platforms creates additional challenges for democratic governance that require international cooperation mechanisms exceeding those developed for previous technological revolutions. Digital governance requires institutional innovations that can coordinate across diverse political systems while maintaining democratic accountability and competitive markets.

Long-term Investment vs. Short-term Returns

Previous technological revolutions created infrastructure through systematic long-term investment that prioritized comprehensive system development over immediate financial returns. Railway infrastructure required decades of coordinated investment in tracks, stations, signaling systems, and regulatory frameworks before achieving full economic benefits. Steel infrastructure required systematic investment in mining, transportation, processing, and standards development before enabling broad economic applications.

Digital infrastructure development has been dominated by short-term financial optimization that prioritizes immediate returns over comprehensive system development. The venture capital model that has financed digital platform development creates incentives for rapid scaling and market dominance rather than systematic infrastructure creation that would serve broad social purposes.

The financialization of digital technology has created speculative dynamics similar to the Frenzy phases of previous technological revolutions, but without the comprehensive infrastructure development that enabled previous cycles to transition successfully through their Turning Points. Digital platforms have achieved remarkable market valuations while failing to create the systematic social infrastructure that would enable broad economic benefits.

Governments have responded to every economic downturn with tremendous deficit stimulus injections into the global economies. Therefore, the complexity and stimulus masks from expanding middle classes, who are losing ground every year. In masking off the real reasons why their pay has remained flat since the 1990s, while costs continue to climb, they have little visibility into the issues driving their continuing economic collapse.

The failure to establish systematic approaches to long-term digital infrastructure investment has prevented the comprehensive system development that would enable transition to the Deployment Period. Unlike previous technological revolutions that created patient capital mechanisms for infrastructure development, digital technology has relied on speculative financing that prioritizes short-term returns over systematic infrastructure creation.

The Extended Turning Point: Symptoms and Consequences

Economic Stagnation and Inequality

Our extended Turning Point manifests through persistent economic stagnation despite remarkable technological advancement. Unlike previous technological revolutions that created broad-based prosperity during their Deployment Periods, digital technology has generated wealth concentration that undermines economic growth and social stability while failing to create the comprehensive employment opportunities that characterized successful technological integration.

During the installation period through the turning point, it was increasingly common for wealth to concentrate at the very top. This has reoccurred in the digital technology cycle; however, since the very top now comprises 25% of the population, the imbalance remains out of view.

The productivity paradox demonstrates how technical advancement has not translated into economic benefits comparable to previous technological revolutions. Despite unprecedented computational capabilities and global connectivity, economic productivity growth has remained sluggish while inequality has increased, indicating fundamental failures in infrastructure creation that prevent broad economic benefits from technological advancement.

Digital platforms have created winner-take-all economic dynamics that concentrate wealth within limited organizations while failing to generate the broad-based economic opportunities that characterized successful technological revolutions. Unlike previous cycles that created comprehensive employment across multiple industries and skill levels, digital technology has created economic polarization that undermines social cohesion and democratic governance.

The failure to create systematic approaches to digital economic distribution has prevented the broad prosperity that would enable social support for continued technological development and institutional innovation. This economic stagnation undermines the social consensus necessary for successful infrastructure creation while creating political instability that prevents effective governance of technological systems.

Political Polarization and Institutional Breakdown

Our extended Turning Point has created political polarization and institutional breakdown that exceed the governance challenges faced during previous technological transitions. Digital platforms have amplified political fragmentation while failing to create the shared experiences and common standards that enabled democratic participation in previous technological revolutions.

The algorithmic coordination mechanisms that enable digital platform efficiency have created information bubbles and echo chambers that undermine democratic discourse while preventing the informed public engagement necessary for effective technological governance. Unlike previous technological revolutions that created shared media and communication infrastructure supporting democratic participation, digital technology has fragmented public discourse while creating systematic misinformation and political manipulation.

The concentration of digital platform infrastructure control has created quasi-governmental power without democratic accountability, undermining traditional institutional frameworks while failing to create effective alternative governance mechanisms. Digital platforms exercise unprecedented influence over economic activity, social communication, and political discourse without the democratic oversight that characterized successful technological governance in previous cycles.

The global scope of digital platforms has created governance challenges that exceed national institutional capabilities while requiring international cooperation mechanisms that have not been successfully developed. This institutional inadequacy prevents effective regulation of digital systems while undermining democratic sovereignty and competitive markets.

Social Fragmentation and Cultural Disruption

Digital infrastructure has created social fragmentation rather than the social cohesion that characterized successful technological revolutions. Unlike previous cycles that established community-level infrastructure supporting shared experiences and democratic participation, digital technology has created isolated individual experiences that undermine social solidarity and collective action capabilities.

The failure to create systematic digital access and literacy infrastructure has created knowledge gaps that prevent broad public understanding of digital systems while undermining democratic participation in technological decision-making. This educational deficit creates social divisions between technical experts and general citizens that exceed the knowledge gaps that characterized previous technological transitions.

Digital platform infrastructures have disrupted traditional social institutions, including journalism, education, and civic organizations, without creating effective replacement mechanisms for democratic participation and social coordination. This institutional disruption has weakened social infrastructure while failing to create alternative coordination mechanisms supporting democratic governance and community welfare.

The speed of digital change has created cultural disruption that exceeds the adaptive capabilities of traditional social institutions while requiring new approaches to social coordination that have not been successfully developed. This cultural instability undermines the social consensus necessary for effective infrastructure creation while creating resistance to technological change that prevents systematic integration.

Pathways Forward: Learning from Historical Success

Regulatory Infrastructure Development

Creating effective digital governance requires systematic regulatory infrastructure development that draws upon lessons from successful technological governance in previous cycles while addressing the unique challenges of digital systems. This regulatory infrastructure must balance technical coordination with democratic accountability while maintaining innovation incentives and competitive markets.

Digital platform regulation requires comprehensive approaches that address market concentration, data privacy, algorithmic accountability, and democratic participation through systematic institutional innovation. These regulatory frameworks must operate at global scale while respecting diverse governance approaches and cultural values through international cooperation mechanisms that exceed previous coordination requirements.

Democratic participation in digital governance requires institutional innovations that translate technical complexity into accessible public discourse while enabling meaningful citizen engagement with infrastructure decisions affecting fundamental aspects of social life and economic organization. These participation mechanisms must balance technical expertise with public accountability while maintaining system effectiveness and innovation capabilities.

Social Infrastructure Investment

Creating comprehensive social infrastructure for digital integration requires systematic investment in education, access, community development, and democratic participation mechanisms that enable broad public engagement with digital technology while maintaining social cohesion and collective action capabilities.

Digital literacy infrastructure must provide universal access to technical education while enabling informed public participation in digital governance decisions. This educational infrastructure must address both technical skills and civic engagement capabilities while supporting lifelong learning and adaptation to technological change.

Community-level digital infrastructure requires systematic investment in local institutions that can coordinate digital technology adoption with community needs and democratic values. These community institutions must balance global connectivity with local autonomy while maintaining social solidarity and collective welfare.

Social safety net infrastructure must address the economic disruption created by digital technology while enabling broad participation in digital economic opportunities. This social infrastructure must provide economic security during technological transition while supporting skill development and economic mobility through systematic approaches to worker protection and development.

Economic Infrastructure Reform

Creating sustainable economic infrastructure for digital integration requires systematic approaches to wealth distribution, market competition, and public investment that address the concentration dynamics created by digital platforms while maintaining innovation incentives and competitive markets.

Digital taxation infrastructure must capture sufficient public revenue from digital economic activity to fund necessary social infrastructure and public services while maintaining competitive markets and innovation incentives. These taxation mechanisms must operate at global scale while respecting diverse fiscal approaches and economic development needs.

Competition policy infrastructure must address the network effects and platform dynamics that create market concentration while preserving the efficiency benefits of digital coordination. This competition infrastructure must balance scale economies with competitive markets while maintaining innovation capabilities and consumer benefits.

Public investment in infrastructure must provide patient capital for comprehensive digital system development that serves broad social purposes while maintaining competitive innovation and private sector efficiency. This investment infrastructure must coordinate public and private resources while maintaining democratic accountability and social benefit optimization.

Next Chapter – Two – Cost Curve Disruptions

Below is the Infrastructure Creation listing for the innovations and bibliographies for Disruptions Dawn within the technology cycle library.

Innovation and Bibliography listing Infrastructure Creation

The main entrance to Technology Cycles Main Library – The Singularity Stacks Link

Link to return to Disruptions Dawn menu