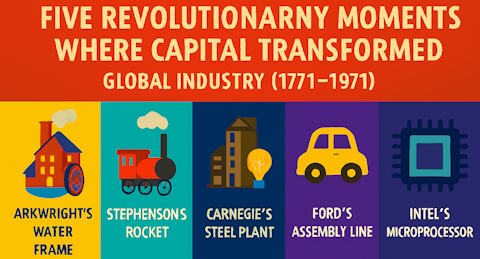

Capital Alignment Across Five Technology Cycles:

From Natural Evolution to Artificial Preservation

The evolution of technological revolutions reveals a fundamental truth that has governed human progress for over two centuries: the alignment of capital determines whether revolutionary technologies create broad-based prosperity or remain trapped in cycles of speculation and stagnation. Carlota Perez’s framework of technological cycles demonstrates that each major technological revolution follows predictable patterns of capital flow, from initial productive investment through speculative excess to crisis-driven reallocation that enables golden age deployment.

Across five technological cycles—from Arkwright’s water frame to Intel’s microprocessor—capital alignment has served as the primary mechanism determining technological success or failure. The Installation Period of each cycle reveals identical patterns: Big Bang events initially attract productive investment toward genuine innovation, but capital gradually shifts toward speculative financial engineering during the Frenzy phase, creating unsustainable bubbles that collapse during Turning Point crises. These crises, while painful, serve an essential function by eliminating speculative malinvestment and forcing capital reallocation toward productive channels that enable Deployment Period prosperity.

The Fifth Cycle as Anomaly

However, the fifth cycle presents an unprecedented anomaly. For the first time in technological history, governments possess sufficient fiscal and monetary tools to prevent the natural capital clearing mechanisms that have enabled all previous cycles to complete their transitions from installation to deployment. The Information Age, launched by Intel’s microprocessor revolution in 1971, has remained trapped in an extended Turning Point for over two decades because artificial intervention has prevented the capital reallocation necessary for golden age deployment. This systematic prevention of natural capital clearing represents perhaps the greatest obstacle to realizing the enormous potential benefits of information-age technologies.

Understanding how capital alignment has evolved across technological cycles provides crucial insights into why the fifth cycle remains stalled and what policy changes are necessary to restore natural capital clearing mechanisms that can complete the information age transition and unlock unprecedented prosperity for human civilization.

The Natural Capital Evolution Pattern

The analysis of technological cycles reveals a consistent pattern of capital evolution during Installation Periods that has remained remarkably stable across over two centuries of technological development. This pattern begins with Big Bang events that demonstrate revolutionary technological capabilities and attract initial productive investment toward genuine innovation and infrastructure development. The Irruption phase witnesses capital flowing toward authentic technological advancement, creating real economic value through improved productivity and new capabilities.

However, as the Installation Period progresses, capital gradually shifts from productive investment toward speculative financial engineering during the Frenzy phase. Successful early investments create demonstration effects that attract increasing amounts of speculative capital seeking extraordinary returns without corresponding productive investment. Financial innovation and stock manipulation begin dominating over genuine technological development, creating asset bubbles that become increasingly disconnected from productive economic activity.

This speculative excess inevitably culminates in Turning Point crises when bubbles collapse and speculative investments are revealed as unsustainable. While these crises impose significant short-term costs, they serve an essential evolutionary function by eliminating malinvestment and forcing capital reallocation toward genuinely productive uses. The natural clearing mechanisms during Turning Points enable efficient operators to acquire failed competitors’ assets at discounted prices while ensuring that capital flows toward proven business models and systematic technological development.

The crisis-driven capital reallocation creates conditions for Deployment Period prosperity by aligning financial capital with productive investment in ways that enable broad-based technological benefits. The golden age phases of previous cycles emerged precisely because Turning Point crises had cleared speculative excess and established capital allocation patterns that rewarded genuine value creation rather than financial manipulation.

Cycle 1: Industrial Revolution – The Foundation of Capital Clearing

The Industrial Revolution established the foundational pattern of capital alignment that would characterize all subsequent technological cycles. Arkwright’s water frame, introduced in 1771, served as the Big Bang event that demonstrated how mechanical production could generate unprecedented profits through systematic factory organization and consistent product quality. This technological breakthrough attracted merchant capital that had been accumulated through overseas trade, creating the first systematic flow of investment capital toward industrial manufacturing.

During the Irruption phase of the 1770s and early 1780s, capital flowed productively toward genuine textile mill construction and infrastructure development. Investors funded water power systems, mechanical equipment, and worker housing that created real economic value through improved productivity and expanded production capacity. The Cromford Mill exemplified this productive capital deployment, with systematic investment in buildings, machinery, and community infrastructure that supported efficient textile production while creating employment opportunities and regional economic development.

However, the success of early textile investments gradually attracted speculative capital during the Frenzy phase of the late 1780s and early 1790s. Capital began flowing toward marginal textile schemes that lacked the water power advantages or systematic organization that had made early ventures successful. Investment shifted from productive assets toward textile company speculation and commodity trading that extracted value rather than creating productive capacity. Speculative ventures in unsuitable locations received funding despite poor fundamentals, as investors sought to replicate early successes without understanding the technical and organizational requirements for textile manufacturing efficiency.

The Natural Clearing Mechanism

The Turning Point crisis of 1793-1797 provided the natural clearing mechanism that eliminated speculative excess while preserving productive capacity. Economic disruption caused speculative textile investments to fail, forcing the liquidation of ventures that lacked genuine competitive advantages. Failed textile companies sold equipment and facilities at discount prices, enabling efficient operators like Arkwright’s mills to acquire additional productive assets at favorable terms. This capital reallocation process concentrated resources in the most efficient textile producers while eliminating speculative waste.

The crisis-driven capital clearing enabled the textile industry to enter its Deployment phase with capital aligned toward proven manufacturing methods and systematic factory organization. Rather than continuing speculation on marginal ventures, capital flowed toward expanding successful mills and improving manufacturing processes that created genuine economic value. This productive capital alignment supported the golden age of textile manufacturing that provided employment, improved living standards, and created the industrial foundation for subsequent technological development.

Cycle 2: Railway Age – Systematic Capital Mobilization and Clearing

The Railway Age demonstrated how capital alignment patterns established during the Industrial Revolution could be scaled to unprecedented levels through systematic capital mobilization mechanisms. Stephenson’s Rocket locomotive, successful on the Liverpool-Manchester Railway in 1829, served as the Big Bang event that proved steam railway technology could generate substantial profits through freight and passenger transport services. This demonstration of commercial viability triggered massive capital mobilization through joint-stock companies that could aggregate investment from thousands of individual shareholders.

The Irruption phase of the 1830s witnessed productive capital deployment toward genuine railway infrastructure development. Investment flowed toward track construction, locomotive manufacturing, station building, and the systematic engineering works required for reliable railway operation. The London & Birmingham Railway exemplified systematic capital deployment, with coordinated investment in track, engineering works, and rolling stock that created integrated transportation networks capable of generating sustained revenue through improved transport efficiency.

Railway development during this period created real economic value by dramatically reducing transportation costs and enabling geographic economic integration that had been impossible with previous transportation technologies. Capital investment in railway infrastructure generated genuine productivity improvements that benefited both railway companies and the broader economy through improved access to markets and reduced costs for goods and services.

Railway Mania

However, the success of early railway investments triggered the Railway Mania of the 1840s, during which capital shifted from productive railway development toward speculative railway schemes with minimal economic justification. Parliament authorized hundreds of railway companies with no serious technical feasibility analysis or economic demand assessment. Capital flooded toward railway stock speculation rather than operational railway investment, creating financial engineering schemes that extracted value from investors without creating corresponding productive capacity.

The speculative excess reached unsustainable levels as railway companies received massive investment despite having no realistic prospects for completing construction or generating sufficient revenue to justify their capital requirements. Railway stock manipulation became more profitable than railway operation, creating systematic misallocation of capital away from genuine transportation improvements toward financial manipulation that served speculator interests rather than economic productivity.

The Turning Point crisis of 1848-1850 eliminated railway speculation through natural market clearing mechanisms. The railway bubble collapsed as speculative railway companies proved unable to complete construction or generate projected revenues, forcing mass liquidation of failed ventures. Railway assets including partially built tracks, equipment, and route authorizations were sold at fractions of their original investment cost, enabling efficient railway operators to acquire these resources for systematic railway network development.

The crisis-driven consolidation enabled viable railway companies to assemble comprehensive railway networks by acquiring failed competitors’ assets and routes at discounted prices. Capital allocation shifted from railway stock speculation toward operational railway investment focused on completing integrated networks that could generate sustained revenue through genuine transportation services. This productive capital realignment enabled the railway industry to achieve its deployment phase prosperity through systematic network operation that transformed economic geography and created broad-based benefits through improved transportation efficiency.

Cycle 3: Steel and Electrical Age – Industrial Capital Integration

The Steel and Electrical Age demonstrated how capital alignment patterns could enable unprecedented industrial integration and systematic technological development. Carnegie’s steel production integration, beginning in 1875, served as the Big Bang event that proved heavy industry could achieve massive scale and efficiency through systematic organization and vertical integration. This demonstration attracted capital toward integrated industrial complexes that could coordinate multiple production stages while achieving cost advantages through systematic management.

During the Irruption phase from 1875 to 1884, capital flowed productively toward genuine industrial development including steel production, electrical systems, and heavy machinery manufacturing. Investment funded integrated industrial complexes, electrical power systems, and the systematic research and development capabilities that enabled continuous technological improvement. Carnegie Steel Works exemplified systematic capital deployment in blast furnaces, rolling mills, and transportation systems that created unprecedented productive capacity while maintaining competitive cost structures.

The electrical systems development during this period demonstrated how capital could enable entirely new categories of economic activity through systematic technological innovation. Investment in electrical power generation and distribution created infrastructure that enhanced manufacturing precision and flexibility while enabling new forms of production and consumption that had been impossible with previous power sources. This productive capital deployment generated real economic value through improved industrial capability and expanded economic opportunities.

Industrial Integration

However, the success of integrated industrial ventures gradually attracted speculative capital during the Frenzy phase from 1884 to 1893. Capital began flowing toward industrial combinations and trust formations that emphasized financial engineering over operational efficiency. Speculative industrial trusts were formed through stock manipulation rather than genuine integration of productive capacity, creating artificial market combinations that extracted value from investors without generating corresponding industrial improvements.

The speculative industrial combinations relied on financial manipulation and market control rather than productive efficiency, creating systematic misallocation of capital away from genuine industrial development toward rent extraction that concentrated wealth without improving productive capacity. Industrial stock speculation became more profitable than industrial operation, preventing capital from flowing toward technological innovations that could enhance productivity and economic growth.

The Turning Point crisis of 1893-1895, known as the Long Depression, eliminated industrial speculation through natural market clearing mechanisms. Speculative industrial combinations collapsed as their stock manipulation schemes proved unsustainable, forcing liquidation of ventures that lacked genuine productive capacity. Industrial assets were sold at discount prices, enabling efficient operators like Carnegie Steel to acquire failed competitors’ facilities and consolidate industry assets under systematic management.

The crisis-driven consolidation enabled efficient industrial operators to achieve unprecedented scale through acquiring failed competitors’ productive assets while eliminating speculative overhead and financial manipulation. Capital allocation shifted from industrial stock speculation toward systematic management of large-scale industrial operations that could achieve genuine efficiency improvements through integrated production and scientific management principles. This productive capital realignment enabled the steel and electrical industries to enter their deployment phase with capital focused on operational efficiency and technological innovation rather than financial manipulation.

Cycle 4: Automobile Age – Mass Production Capital Revolution

The Automobile Age demonstrated how capital alignment could enable mass production systems that created broad-based prosperity through systematic production methods and mass consumer markets. Ford’s Highland Park assembly line, perfected in 1908, served as the Big Bang event that proved mass production could achieve unprecedented scale and affordability through systematic work organization and standardized production processes. The Model T success demonstrated that systematic production methods could create mass consumer markets while generating substantial profits through volume production.

The Irruption phase from 1909 to 1920 witnessed productive capital deployment toward genuine automobile manufacturing and mass production infrastructure. Investment flowed toward assembly line equipment, supplier network development, and the systematic tooling and machinery required for efficient mass production. Ford’s Highland Park Plant exemplified systematic capital deployment in assembly line machinery, conveyor systems, and precision tooling that enabled unprecedented production volumes while maintaining quality standards and cost control.

Mass production investment during this period created real economic value by making automobiles affordable for middle-class consumers while generating employment opportunities in manufacturing and related industries. Capital investment in mass production infrastructure enabled productivity improvements that reduced costs while improving product quality, creating genuine economic benefits for both producers and consumers through systematic production efficiency.

The automobile industry’s productive capital deployment also enabled complementary infrastructure development including supplier networks, distribution systems, and service networks that created comprehensive economic ecosystems supporting automobile adoption and use. This systematic capital allocation created multiplier effects that generated employment and economic opportunity across multiple sectors while enabling the geographic mobility and economic flexibility that characterized modern industrial society.

The Roaring Twenties

However, the success of mass production created speculative capital flows during the Frenzy phase of the Roaring Twenties from 1920 to 1929. Capital shifted from productive automobile manufacturing toward automobile stock speculation and consumer credit schemes that extracted value rather than creating productive capacity. Speculative investment in automobile companies with marginal production capabilities received funding despite lacking the systematic organization and production efficiency that made successful companies profitable.

Consumer credit expansion became divorced from productive capacity as financial institutions created credit bubbles that enabled automobile purchases beyond sustainable income levels. Capital allocation shifted toward financial engineering that generated short-term profits through credit manipulation rather than productive investment that enhanced manufacturing capability and economic productivity. Stock market speculation on automobile and related companies created artificial valuations that bore little relationship to productive economic activity.

The Turning Point crisis of 1929-1943, culminating in the Great Depression, eliminated automobile speculation through the most severe capital clearing process in modern history. The stock market collapse eliminated speculative capital while industrial overcapacity and consumer credit defaults forced systematic restructuring of automobile and related industries. Failed automobile companies were liquidated, with assets acquired by efficient producers that could maintain operations through superior production methods and financial management.

Crises

The crisis-driven consolidation enabled surviving automobile companies—General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler—to acquire failed competitors’ facilities and technology while eliminating speculative overhead and financial manipulation. Government infrastructure investment in highways and related systems complemented private capital reallocation toward genuine automobile production and distribution, creating integrated systems that supported mass automobile adoption and use.

The productive capital realignment enabled the automobile industry to achieve deployment phase prosperity through systematic mass production that created broad-based economic benefits. Capital flowed toward proven production methods and systematic quality improvement rather than speculative schemes, enabling the golden age of automobile manufacturing that provided middle-class employment opportunities and consumer access to transportation that transformed American society and economic organization.

Cycle 5: Information Age – The Prevented Capital Clearing

The Information Age represents a fundamental departure from the natural capital alignment patterns that characterized previous technological cycles, creating an unprecedented situation where artificial intervention has prevented the capital clearing mechanisms necessary for deployment phase prosperity. Intel’s 4004 microprocessor, introduced in 1971, served as the Big Bang event that demonstrated information processing could achieve exponential performance improvements with dramatic cost reductions, proving that digital technologies could create unprecedented economic value through systematic innovation and Moore’s Law scaling effects.

The Irruption phase from 1971 to 1987 initially followed historical patterns with productive capital deployment toward genuine technological development. Investment flowed toward computer hardware development, software innovation, and networking infrastructure that created real economic value through improved productivity and entirely new categories of economic activity. Intel’s microprocessor development and Microsoft’s operating system innovation exemplified systematic capital deployment in research and development, manufacturing capability, and market development that created foundational technologies for information-age economic transformation.

During this productive phase, capital investment enabled revolutionary improvements in computing capability while creating new industries including personal computers, software applications, and networking systems that generated genuine economic value through enhanced productivity and expanded economic opportunities. The systematic development of information technologies created multiplier effects across multiple sectors while demonstrating unprecedented potential for economic growth and social advancement through digital innovation.

However, the Frenzy phase from 1987 to 2000 witnessed the familiar shift from productive investment toward speculative financial engineering that had characterized previous cycles. The dot-com boom created massive capital flows toward internet company speculation regardless of business model viability or path to profitability. Companies like Pets.com, Webvan, and hundreds of other internet ventures received enormous investment despite having no realistic prospects for generating revenue sufficient to justify their valuations.

Capital Allocations

Capital allocation during the dot-com era shifted from genuine technology development toward stock manipulation and financial engineering that extracted value from investors without creating corresponding productive capacity. Internet stock speculation became more profitable than internet service provision, creating systematic misallocation of capital away from technological innovation toward rent extraction that concentrated wealth without generating corresponding economic value.

The natural Turning Point crisis began with the dot-com collapse of 2000-2002, following historical patterns as technology stock speculation proved unsustainable and speculative internet companies faced liquidation. Failed internet companies began selling assets including technology, talent, and customer bases to efficient operators, initiating the natural capital clearing process that should have reallocated resources toward productive technology development.

However, unlike previous cycles, the natural capital clearing process was systematically prevented through unprecedented government intervention. The “too big to fail” policy, implemented most comprehensively after 2008, artificially preserved failing institutions that should have been liquidated through normal market processes. Massive fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing prevented natural capital reallocation by providing artificial support to zombie banks, corporations, and technology platforms that had demonstrated fundamental business model failures.

The artificial preservation mechanisms created systematic distortions in capital allocation that have prevented information age deployment for over two decades. Failed banks like Bank of America, Citigroup, and Wells Fargo received bailouts instead of liquidation, preventing capital reallocation to efficient financial institutions that could better serve digital commerce requirements. Technology platforms including Facebook, Google, and Amazon maintained market positions through artificial barriers rather than competitive pressure, enabling surveillance capitalism business models that extract value rather than creating genuine technological advancement.

Speculation

Speculative capital continues flowing toward financial engineering, private equity manipulation, and platform rent extraction rather than productive technology investment because quantitative easing and zero interest rates enable continued speculation without natural market discipline. Capital that should be funding genuine information-age innovation is instead supporting zombie institutions and extractive business models that prevent technological advancement and social benefit.

The systematic prevention of capital clearing has created resource misallocation where capital flows toward speculation, rent-seeking, and zombie institution preservation rather than genuine technological innovation that could enable information-age golden age prosperity. Platform companies optimize for surveillance and behavioral manipulation rather than user service because artificial competitive barriers prevent natural market discipline that would force business model innovation toward genuine value creation.

Most critically, the prevented capital clearing has eliminated the crisis-driven democratic pressure that historically forced appropriate institutional development for technological deployment. Previous Turning Point crises created social conditions that generated democratic consensus for institutional innovations including social security, labor rights, infrastructure investment, and corporate governance reforms that enabled broad-based prosperity during deployment phases. The artificial prevention of crisis has eliminated democratic engagement with fundamental questions about technological governance and institutional adaptation necessary for information-age deployment.

The Consequences of Prevented Capital Alignment

The systematic prevention of natural capital clearing during the fifth cycle has created unprecedented obstacles to technological advancement and social prosperity that demonstrate the essential role of capital alignment in enabling golden age deployment. Unlike previous cycles where Turning Point crises cleared speculative excess and enabled productive capital reallocation, artificial intervention has preserved exactly the institutional and financial structures that prevent information-age benefits from reaching broad segments of society.

The most visible consequence of prevented capital clearing is the continuation of extractive business models that would have been eliminated by natural competitive pressure. Social media platforms optimize for addiction and behavioral manipulation rather than genuine communication and community building because artificial preservation prevents competitive alternatives that would better serve user interests. Search engines prioritize advertising revenue over information quality because monopoly protection eliminates market pressure for genuine service improvement.

Educational institutions represent perhaps the most destructive example of prevented capital clearing, as artificial funding mechanisms preserve obsolete approaches to skill development while creating enormous debt burdens that prevent access to genuine professional development opportunities. Rather than natural market processes eliminating ineffective educational approaches and rewarding innovative skill development programs, artificial subsidies enable credential inflation and debt extraction that serves institutional interests rather than student advancement.

Financial Institutions

Financial institutions continue operating with business models designed for industrial-age requirements rather than information-age needs because artificial preservation prevents the competitive pressure that would force innovation toward digital commerce, global coordination, and innovation financing capabilities. Zombie banks consume resources that should support genuine financial innovation while providing inferior service and preventing development of financial systems suited to information-age economic requirements.

The prevented capital clearing has also eliminated the democratic pressure that historically drove institutional adaptation and social innovation during technological transitions. Previous Turning Point crises created social conditions that forced collective engagement with fundamental questions about technological governance, institutional design, and social adaptation that enabled deployment phase prosperity through genuine democratic consensus and institutional innovation.

Without crisis pressure forcing democratic participation in technological governance and institutional development, elite management and corporate control proceed without public accountability or social value alignment. Major decisions about platform design, algorithmic systems, data usage, and technological development priorities occur through corporate board rooms rather than democratic deliberation, creating systematic democratic deficits that prevent public participation in fundamental choices about technological development and social organization.

Policy Implications: Restoring Natural Capital Clearing

Completing the fifth technological cycle and achieving information-age golden age prosperity requires comprehensive policy reforms that restore natural capital clearing mechanisms while protecting individuals and communities from adjustment costs through enhanced social insurance and democratic participation systems.

The most critical reform involves eliminating artificial preservation mechanisms that prevent natural capital reallocation. Companies demonstrating sustained competitive failure should be allowed to fail through normal bankruptcy processes, with displaced workers receiving comprehensive transition support including retraining, income maintenance, and healthcare coverage during career transitions. This approach protects individuals while enabling market forces to reallocate resources toward genuinely productive uses that create employment opportunities in information-age sectors.

Platform monopolies must be broken up through structural separation that prevents cross-subsidization and self-dealing, creating competitive pressure for genuine value creation and user service rather than surveillance capitalism and behavioral manipulation. Data portability and interoperability standards should enable users to switch between competing platforms while maintaining digital assets and social connections, eliminating network effect lock-in while preserving user choice and competitive innovation.

Educational institution reform requires eliminating artificial funding that preserves ineffective credentialing systems while creating competitive markets for educational services that reward demonstrable skill development and career advancement. Income-share agreements, employer-sponsored training, and competency-based assessment should replace credential gatekeeping with market mechanisms that align educational provider incentives with student success and genuine professional preparation.

The Rules Need to Apply to All

Most critically, elite criminal accountability must be restored through genuine prosecution of corporate executives and platform leaders who engage in systematic fraud, market manipulation, or demonstrable harm to users and democratic processes. Prosecutorial accountability should focus on clear criminal violations while ensuring asset recovery and community restitution that eliminates profit incentives for extractive business practices.

However, natural capital clearing must be accompanied by enhanced social insurance and democratic participation systems that enable beneficial technological change without imposing excessive costs on individuals and communities. Community-based cooperative approaches to healthcare, housing, and social support can provide mutual aid and shared risk management while building social capital and collective adaptation capability rather than bureaucratic dependency.

Professional communities should emerge through voluntary association that provides portable benefits, continuous skill development, and mutual support for information-age work patterns while enabling individual autonomy and career flexibility. Democratic institutions must enable informed public participation in technological development priorities and platform governance through deliberative processes that combine citizen engagement with technical expertise and democratic accountability.

Capital Alignment as the Key to Information Age Prosperity

The analysis of capital alignment across five technological cycles reveals that the systematic prevention of natural clearing mechanisms represents the primary obstacle to completing the information age transition and achieving unprecedented prosperity through digital innovation. Historical patterns demonstrate conclusively that capital alignment determines whether revolutionary technologies create broad-based benefits or remain trapped in cycles of speculation and extraction that serve elite interests while preventing social advancement.

The first four technological cycles succeeded because Turning Point crises eliminated speculative excess and forced capital reallocation toward productive investment that enabled golden age deployment. Each crisis, while imposing short-term costs, served essential evolutionary functions by clearing malinvestment and creating conditions where capital flowed toward genuine value creation rather than financial manipulation and rent extraction.

The fifth cycle remains stalled precisely because artificial intervention has prevented these natural clearing mechanisms for over two decades, creating systematic misallocation of capital toward speculation, surveillance capitalism, and zombie institution preservation rather than productive technological innovation. The enormous potential benefits of information-age technologies—including global knowledge sharing, enhanced human creativity, cooperative economic organization, and environmental sustainability—remain unrealized because capital continues flowing toward extraction rather than value creation.

Restoration

Restoring natural capital clearing while providing appropriate social insurance and democratic participation systems offers the most promising path toward completing the information age transition and unlocking golden age prosperity that serves genuine human needs and social values. The historical record demonstrates that human societies possess remarkable capabilities for beneficial adaptation to technological change when natural processes of competition, cooperation, and democratic engagement are allowed to operate effectively.

Success in completing the fifth technological cycle requires recognizing that artificial preservation has become the primary obstacle to information-age prosperity and that comprehensive reform eliminating artificial barriers while building democratic institutions can enable beneficial technological development that serves broad-based human flourishing rather than narrow elite interests. The lessons learned from capital alignment across five technological cycles provide essential guidance for policy development that can restore natural adaptive processes and achieve the unprecedented prosperity that information-age technologies make possible for human civilization.

The stakes could not be higher. The information age possesses technological capabilities that could eliminate poverty, enhance human creativity, enable global cooperation, and create environmental sustainability beyond anything achieved in human history. However, realizing these benefits requires restoring the natural capital alignment mechanisms that have enabled all previous technological revolutions to complete their transitions from speculative excess to productive deployment. Only through comprehensive reform that eliminates artificial preservation while building democratic institutions can society complete the current technological transition and create foundations for continued technological advancement that serves human flourishing and environmental stewardship for generations to come.

Next Chapter Nine: Market Alignment

Below is the Capital Alignment listing for the innovations and bibliographies for Disruptions Dawn within the technology cycle library.

Innovation and Bibliography listing Capital Alignment

The main entrance to Technology Cycles Main Library – The Singularity Stacks Link