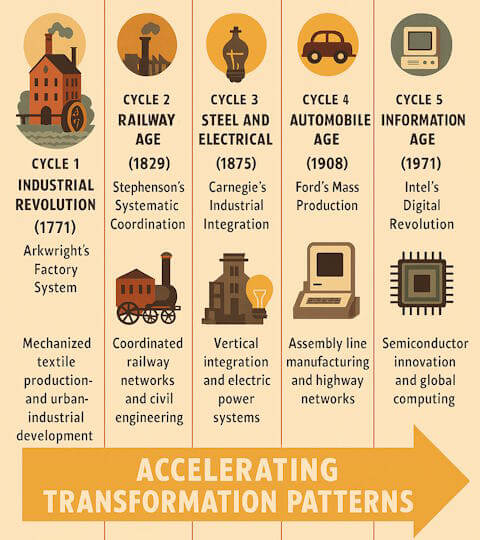

Five Technological Revolutions That Transformed Society:

The Economics of Social Change

Humanity has experienced five major technological revolutions since 1771. Each revolution fundamentally transformed how societies organize production, distribute wealth, and coordinate human activity. These transformative periods created new institutions while destroying old systems.

Furthermore, each cycle followed predictable patterns of development, crisis, and resolution. The analysis reveals how technological innovation interacts with financial systems, educational institutions, and social structures. Understanding these patterns helps societies prepare for future technological transitions.

Meanwhile, the progression from Arkwright’s water frame to Intel’s microprocessor demonstrates accelerating technological complexity. Each cycle built upon previous achievements while creating entirely new possibilities for human organization and economic development.

Cycle 1: The Industrial Revolution (1771) – From Craft to Factory

Arkwright’s Revolutionary Water Frame

Richard Arkwright’s water frame transformed textile production in 1771. The invention mechanized cotton spinning while maintaining consistent thread quality. Previously, textile workers operated individual spinning wheels in their homes.

Subsequently, Arkwright constructed the first modern factory at Cromford Mill. The facility concentrated workers under systematic supervision and rigid schedules. Water power drove multiple spinning frames simultaneously, dramatically increasing productivity.

Moreover, the system required new forms of work discipline and social organization. Workers adapted to factory bells, shift schedules, and continuous machine operation. Traditional craft knowledge gave way to mechanical expertise and systematic maintenance procedures.

Socioeconomic Foundations for Change

British society possessed unique advantages that enabled industrial transformation. Merchant capital accumulated through overseas trade provided investment resources. Additionally, enclosure acts displaced rural populations, creating available factory workers.

Colonial cotton imports supplied cheap raw materials for textile manufacturing. Furthermore, established shipping networks distributed finished goods to global markets. These upstream and downstream linkages supported rapid factory system expansion.

The patent system protected Arkwright’s innovations while encouraging further technological development. Legal frameworks evolved to support industrial organization and capital formation. Insurance systems managed new categories of business risk associated with factory operations.

Institutional Innovations and Social Change

Factory towns like Cromford created new forms of community organization. Companies provided worker housing, schools, and retail facilities. These arrangements established precedents for corporate social responsibility and systematic employee management.

However, working conditions remained harsh by modern standards. Child labor, long hours, and dangerous machinery created significant social problems. Nevertheless, steady wages attracted workers from agricultural regions experiencing economic displacement.

The transformation established patterns of urban-industrial development that persisted for centuries. Geographic concentration of manufacturing created agglomeration economies. Specialized skills and supplier networks developed around industrial centers, reinforcing competitive advantages.

Cycle 2: Railway Revolution (1829) – Systematic Coordination Emerges

Stephenson’s Rocket and Transportation Revolution

George Stephenson’s “Rocket” locomotive achieved unprecedented reliability and speed in 1829. The railway system demonstrated how systematic engineering could coordinate complex operations across extended networks. Telegraph communication enabled real-time coordination of train movements.

Railway development required massive capital investments exceeding previous industrial ventures. Joint-stock companies mobilized savings from thousands of middle-class investors. Parliamentary approval processes established systematic procedures for large-scale infrastructure projects.

Additionally, railway construction employed tens of thousands of workers in coordinated engineering projects. The Liverpool-Manchester Railway proved commercial viability of steam locomotion. Success triggered rapid expansion across Britain and international technology transfer.

Technical Standardization and Network Effects

Railway systems achieved unprecedented levels of technical standardization. Standard gauge tracks enabled interoperability across different railway companies. Locomotive designs converged on successful engineering principles tested through systematic experimentation.

Timetabling required national adoption of Greenwich Mean Time. Signal systems prevented accidents through systematic traffic control procedures. Station designs standardized passenger facilities while adapting to local conditions and traffic volumes.

Furthermore, railway operations created the first comprehensive real-time information systems. Telegraph networks coordinated train movements across hundreds of miles. Systematic record-keeping tracked passengers, freight, and operational performance with unprecedented precision.

Professional Engineering Development

Railway construction established civil engineering as a systematic profession. The Institution of Civil Engineers developed professional standards and educational requirements. Technical knowledge became codified in manuals, specifications, and training programs.

International technology transfer accelerated through professional networks and systematic documentation. British engineers supervised railway construction across Europe, North America, and colonial territories. Professional mobility facilitated rapid global diffusion of railway technology.

Moreover, railway companies pioneered modern corporate management structures. Divisional organization coordinated operations across extended networks. Systematic accounting tracked costs and revenues with unprecedented detail and accuracy.

Cycle 3: Steel and Electrical Age (1875) – Industrial Maturation

Carnegie Steel and Industrial Integration

Andrew Carnegie’s steel empire demonstrated vertical integration possibilities in heavy industry. The company controlled iron ore mines, transportation systems, and steel production facilities. Systematic cost accounting enabled competitive pricing and continuous efficiency improvements.

Bessemer steel processes reduced production costs while improving quality. Open hearth furnaces provided precise control over steel composition. Continuous casting systems integrated ore processing with finished steel production in single facilities.

Additionally, steel standardization enabled skyscraper construction and modern infrastructure development. ASTM specifications ensured consistent quality across different producers. Structural steel transformed urban architecture while supporting industrial expansion.

Electrical Power System Development

Edison’s Pearl Street Station demonstrated central power generation feasibility. Electric lighting systems transformed urban life while creating new business opportunities. AC power transmission enabled efficient distribution across extended networks.

Electric motors revolutionized factory organization by eliminating mechanical power transmission systems. Workers gained flexibility in production layout while achieving improved efficiency. Variable speed control enabled precise manufacturing processes.

Furthermore, telephone systems created real-time communication networks within cities. Electric streetcars provided reliable urban transportation serving growing metropolitan areas. Elevator systems enabled vertical urban development through safe, efficient transportation.

Corporate Research and Development

General Electric established the first systematic industrial research laboratory. Professional scientists worked on applied research problems with commercial applications. Patent portfolios protected innovations while generating licensing revenues.

Scientific management principles optimized production processes through systematic analysis. Time and motion studies identified efficiency improvements in manufacturing operations. Cost accounting systems provided detailed financial control over complex operations.

Meanwhile, investment banking coordinated large-scale corporate consolidations. Securities markets enabled public ownership of major industrial enterprises. Professional management separated ownership from operational control in large corporations.

Cycle 4: Automobile Age (1908) – Mass Production Revolution

Ford’s Assembly Line Innovation

Henry Ford’s Highland Park Plant revolutionized manufacturing through moving assembly lines. Production time for Model T automobiles decreased from 12.5 hours to 1.5 hours. Interchangeable parts enabled field service and reduced manufacturing complexity.

Scientific work analysis optimized labor productivity through systematic task division. The five-dollar day attracted skilled workers while reducing turnover costs. Mass production enabled dramatic cost reductions making automobiles affordable for middle-class consumers.

Moreover, Ford’s system demonstrated how standardization could support product quality while achieving economies of scale. Statistical quality control ensured consistent performance and reliability. Systematic maintenance procedures extended product life and customer satisfaction.

Infrastructure and Market Development

Highway development created comprehensive transportation networks supporting automobile adoption. Gasoline distribution systems provided nationwide fuel access through service station networks. Automotive service systems ensured maintenance and repair availability across the country.

Consumer credit systems enabled working families to purchase expensive durable goods. General Motors Acceptance Corporation pioneered systematic installment financing. Insurance systems managed risks associated with automobile ownership and operation.

Additionally, suburban development patterns reflected automobile accessibility requirements. Shopping centers concentrated retail facilities serving automobile-accessible markets. Drive-in services adapted business models to automobile-oriented consumer preferences.

Social and Cultural Transformation

Automobile ownership transformed family life and social relationships. Geographic mobility enabled new forms of courtship, recreation, and community participation. Suburban lifestyles became possible through reliable individual transportation.

Women gained increased independence through automobile access to employment and social opportunities. However, automotive culture also reinforced traditional gender roles through marketing and design preferences. Youth culture developed around automobile ownership and customization.

Furthermore, automobile manufacturing became central to American economic identity and international competitiveness. Mass production principles spread across multiple industries. Labor unions achieved significant gains through industrial organization and collective bargaining.

Cycle 5: Information Age (1971) – Digital Platform Dominance

The Microprocessor Revolution

Intel’s 4004 microprocessor launched the information age in 1971. Semiconductor manufacturing enabled dramatic cost reductions while increasing computational power exponentially. Moore’s Law described systematic performance improvements over extended periods.

Personal computers democratized computing access while creating new categories of professional activity. Software development became a major industry employing millions of knowledge workers. Programming languages enabled systematic creation of complex applications.

Additionally, networking protocols connected computers globally through standardized communication systems. Internet development created unprecedented capabilities for information sharing and coordination. Email systems transformed business communication while enabling global collaboration.

Digital Platform Economics and Social Fragmentation

Platform-based business models created value through enabling third-party innovation and interaction. Microsoft Windows and Intel processors formed the “Wintel” standard for personal computing. Application developers created thousands of software programs serving diverse user needs.

However, unlike previous technological revolutions that created broad social cohesion around shared infrastructure (railways, electrical grids, highways), digital platforms generated unprecedented social fragmentation. Network effects produced winner-take-all competitive dynamics that concentrated not just economic power, but social and cultural influence within a small number of technology companies.

Search engines, social media platforms, and e-commerce systems achieved global dominance rapidly, but rather than creating shared public spaces like previous technologies, they created algorithmic echo chambers that reinforced existing social divisions. Digital advertising revenue models optimized for engagement and attention capture, systematically amplifying divisive content over consensus-building information.

Knowledge Economy and the Failure of Social Integration

Information technology created predominantly knowledge-based employment requiring continuous learning and adaptation. Professional success depended on maintaining currency with rapidly changing technologies. Formal education became essential for most career opportunities.

Yet society failed to develop the social institutions necessary for broad-based participation in this transformation. Unlike previous cycles where public education expanded systematically to meet industrial needs, the information age created a bifurcated learning system. Elite institutions and communities developed sophisticated digital literacy and adaptive learning capabilities, while much of society was left with obsolete educational models designed for industrial-age compliance rather than knowledge-age creativity and problem-solving.

Remote work capabilities enabled geographic flexibility while accessing global talent pools, but this mobility primarily benefited already-privileged knowledge workers. Rather than creating new forms of community and social solidarity, digital technologies enabled the wealthy and educated to opt out of local institutions and shared civic life, weakening the social bonds that previous technological transitions had strengthened.

Digital Divides and Cultural Resistance

The information age created multiple overlapping digital divides that prevented the social consensus necessary for completing the technological transition. These weren’t merely economic gaps, but fundamental differences in worldview, values, and social organization:

Generational Divides: Unlike previous technologies that societies adopted gradually across all age groups, digital technologies created unprecedented generational gaps. Younger populations became “digital natives” with fundamentally different cognitive patterns, social relationships, and economic expectations, while older populations often experienced digital change as cultural assault rather than beneficial progress.

Geographic Cultural Splits: Technology industries concentrated in specific metropolitan areas, creating not just economic disparities but distinct cultural identities. “Tech culture” developed its own values, social norms, and political perspectives that often conflicted directly with traditional communities experiencing economic displacement from technological change.

Educational and Class Polarization: Previous technological revolutions eventually created new middle-class occupations that provided pathways for social mobility. The information age, however, increasingly sorted people into high-skill knowledge work or low-skill service work, with fewer intermediate opportunities. This created not just economic inequality but cultural resentment and political backlash against “experts” and technological progress itself.

The Prevented Turning Point:

How Fiscal Intervention Stalled the Fifth Cycle

The Historical Pattern of Creative Destruction

Previous technological revolutions succeeded because they completed natural cycles of creative destruction. Each turning point required clearing mechanisms—recessions, financial crashes, and business failures that eliminated obsolete institutions and business models while forcing innovation and adaptation:

– The Industrial Revolution: The economic disruptions of the 1810s-1840s cleared away guild systems and feudal arrangements, enabling factory organization and modern labor markets.

– The Railway Age: The railway manias and crashes of the 1840s-1870s eliminated inefficient railway companies while establishing standardized systems and professional management.

– The Steel Electrical Age: The Long Depression of 1873-1896 and subsequent crashes cleared away small-scale production, enabling the large-scale corporate organization necessary for electrical systems and steel production.

– The Automobile Age: The crashes of 1907, 1921, and especially the Great Depression forced institutional innovations—labor unions, social security, corporate governance reforms—that enabled broad-based prosperity during the automobile golden age.

The Fifth Cycle’s Artificial Preservation

The information age represents the first technological revolution where governments possessed sufficient fiscal and monetary tools to prevent these natural clearing mechanisms. Beginning with the response to the 1970s stagflation and accelerating dramatically after 2008, fiscal stimulus, quantitative easing, and “too big to fail” policies have systematically prevented the creative destruction necessary for cycle completion:

Zombie Institution Preservation: Rather than allowing obsolete companies, banks, and business models to fail and be replaced by information-age equivalents, government intervention keeps industrial-age institutions alive. Banks that should have failed in 2008 remain too big to fail. Legacy corporations continue operating through subsidies and bailouts instead of being replaced by genuinely innovative companies. Educational institutions continue delivering industrial-age training instead of adapting to knowledge economy needs.

Resource Misallocation: Fiscal stimulus directs resources toward preserving existing systems rather than building new ones. Bailouts for failing airlines, retailers, and manufacturers prevent resources from flowing to companies developing genuine information-age innovations. Student loans prop up educational institutions that fail to provide relevant skills. Mortgage subsidies maintain suburban development patterns instead of enabling new forms of community organization suited to remote work and digital collaboration.

Elite Protection from Adaptation Pressure: “Too big to fail” mentality means the financial and corporate elites who should bear the costs of technological transition are instead protected from losses. This removes their incentive to adapt business models, invest in productive innovation, or develop new forms of social organization. Platform companies can maintain extractive business models because they never face existential pressure to create genuine value for users and society.

However, the most critical missing element is the absence of personal accountability through criminal prosecution. In previous technological cycles, elite actors who engaged in fraud, market manipulation, or systematic wealth extraction faced genuine legal consequences that created powerful incentives for adaptive behavior. The railway age prosecuted railway barons for securities fraud. The steel age pursued antitrust cases against monopolistic practices. Even the automobile age eventually prosecuted corporate executives for criminal negligence and fraud.

The information age has largely abandoned elite criminal prosecution despite widespread financial gerrymandering, data privacy violations, market manipulation through algorithmic trading, and systematic wealth extraction through platform monopolization. When financial executives orchestrate mortgage fraud that crashes the global economy, they receive bailouts rather than prison sentences. Platform executives design addiction algorithms that harm children and democratic processes, they face congressional hearings rather than criminal charges. When cryptocurrency executives operate obvious Ponzi schemes, they receive minimal sentences while keeping extracted wealth.

Restoring criminal prosecution for elite financial crimes would create the adaptation pressure that fiscal intervention removed. Corporate executives would face genuine personal consequences for extractive business models, forcing innovation toward genuine value creation. Platform companies would need to develop socially beneficial technologies rather than exploitative ones to avoid criminal liability for their leaders. Financial institutions would invest in productive innovation rather than speculative bubbles to avoid prosecution for market manipulation.

This prosecutorial accountability mechanism could serve as the substitute for natural market clearing that fiscal intervention prevented, creating the pressure necessary to move from installation to deployment phase while maintaining economic stability. Elite prosecution would restore the creative destruction dynamic at the leadership level without requiring widespread social crisis.

Borrowing the Future Golden Age

Most critically, massive debt financing and monetary expansion essentially pulls future golden age prosperity into the present to maintain mediocre stability. This creates several devastating effects:

Debt Overhang: The enormous debt burdens accumulated through fiscal stimulus consume future resources that should fund the infrastructure, education, and social systems necessary for information-age prosperity. Future generations inherit debt obligations that prevent the public investment necessary for completing the technological transition.

Asset Bubble Creation: Monetary expansion inflates asset prices rather than funding productive investment. Real estate, stocks, and other financial assets become disconnected from productive value, creating wealth inequality while starving the real economy of investment capital needed for technological deployment.

Innovation Distortion: Easy money flows toward financial engineering and rent-seeking rather than genuine technological innovation. Private equity, hedge funds, and platform monopolies optimize for financial returns rather than social value creation, preventing the broad-based productivity improvements that characterized previous golden ages.

The Social Pressure Release Valve Problem

Perhaps most importantly, preventing economic crashes eliminates the social pressure that historically drove institutional adaptation. Previous turning points created acute social crisis that generated consensus for major reforms:

The New Deal Precedent: The Great Depression created the social conditions necessary for establishing social security, labor rights, banking regulation, and public investment programs that enabled automobile age prosperity. Without crisis pressure, these innovations would never have overcome political resistance.

Institutional Sclerosis: By preventing acute pain, fiscal stimulus also prevents the social consensus needed for institutional change. Educational systems, professional associations, regulatory frameworks, and social safety nets remain frozen in industrial-age configurations because there’s insufficient pressure for adaptation.

Democratic Engagement Prevention: Crisis historically forces democratic participation in major decisions about economic organization and technological governance. Artificial stability allows technological development to proceed through private corporate decisions without democratic input, creating the “democratic deficit” that characterizes the information age.

Social Unreadiness as Prevented Adaptation

The Breakdown of Social Learning Mechanisms

The prevented turning point explains why traditional social learning mechanisms collapsed without replacement. Previous technological revolutions succeeded because societies developed effective mechanisms for collective learning and adaptation through crisis-driven necessity. The railway age created engineering schools, professional associations, and standardized technical training because economic survival depended on technological competence. The automobile age established vocational education, corporate training programs, and systematic skill development pathways because companies needed trained workers to remain competitive.

The information age, however, disrupted these social learning mechanisms without creating equivalent replacement pressure. Fiscal stimulus enabled traditional institutions—schools, unions, professional associations, civic organizations—to survive without adapting, losing relevance and capacity while preventing new institutions from developing:

Institutional Obsolescence Without Replacement: Educational institutions continue operating on industrial-age assumptions about standardized knowledge and credentialed expertise, while the digital economy rewards adaptive learning, creative problem-solving, and continuous skill updating. Because these institutions receive continued funding despite irrelevance, they never face the pressure to innovate that would create information-age educational systems.

Loss of Mentorship Systems: Previous cycles maintained apprenticeship and mentorship relationships that transmitted both technical skills and social norms across generations. Fiscal intervention preserved companies that should have failed, maintaining formal employment structures while eliminating the master-apprentice relationships that enabled skill transfer. Digital technologies disrupted these relationships without crisis pressure forcing the development of equivalent mechanisms for social knowledge transfer.

Fragmented Professional Identity: Unlike previous eras where professional communities developed shared standards and ethical frameworks through competitive pressure and crisis adaptation, digital industries operate in an artificially stable environment that prevents professional cohesion. The result is fragmented, rapidly changing occupational categories with minimal professional cohesion or social responsibility standards because there’s no survival pressure requiring collective organization.

Cultural Values Misalignment and Artificial Stability

Each previous technological revolution eventually achieved broad social acceptance by aligning with fundamental cultural values and social aspirations through crisis-driven adaptation. The Industrial Revolution promised prosperity through hard work and delivered it through competitive pressure. Railways enabled westward expansion and national unity because survival required collective infrastructure investment. Electricity brought comfort and convenience to homes because competitive markets rewarded companies that served consumer needs. Automobiles provided individual freedom and family mobility because the Great Depression created social conditions demanding broad-based prosperity.

The information age, however, created fundamental tensions with core social values that remain unresolved because artificial stability prevents the pressure necessary for cultural adaptation:

Privacy vs. Connectivity: Digital technologies require extensive personal data sharing for functionality, enabling systematic exploitation rather than merely creating privacy concerns. Personal data extraction has become a primary mechanism for transferring wealth from the declining middle class to technology platform owners. User data generates enormous profits for a small number of companies. At the same time, the data providers—ordinary citizens—receive no compensation and experience worsened economic outcomes through algorithmic manipulation of prices, employment opportunities, and access to services. Moreover, this same data infrastructure is used to obscure these exploitative dynamics, with algorithmic systems designed to hide how digital platforms systematically advantage the wealthy while disadvantaging the majority.

The resistance to digital technologies reflects not irrational anxiety about privacy, but rational recognition that personal data sharing primarily serves to accelerate wealth concentration rather than deliver the promised benefits of connectivity. However, because platform companies never face existential competitive pressure or regulatory enforcement, these exploitative business models persist indefinitely rather than being forced to evolve toward genuine value creation.

Community vs. Individualism: While digital platforms enable global connectivity, they often undermine local community bonds and face-to-face social relationships. This creates social isolation and mental health challenges that generate resistance to further technological integration. In previous cycles, competitive pressure would have forced technology companies to develop business models that strengthened rather than weakened social bonds. Fiscal intervention removes this pressure, allowing platforms to optimize for engagement and data extraction regardless of social consequences.

Work vs. Life Integration: Information technologies blur boundaries between work and personal life, but the “always connected” expectation creates a more fundamental problem than stress—it severs society from the productive technological processes needed to complete the cycle transition. Constant connectivity between work demands and social media consumption traps people in reactive, passive relationships with technology rather than the active, creative engagement that characterized previous successful technological adaptations.

When workers spent evenings tinkering with automobiles or learning electrical systems, they developed the hands-on understanding that enabled broad social mastery of those technologies. Today’s always-connected culture prevents this deep engagement—people remain perpetually distracted consumers of digital content rather than becoming technological creators and innovators. Social media algorithms designed for addiction specifically undermine the sustained attention and reflective thinking required for genuine technological learning and adaptation.

This constant distraction breaks the positive feedback loops that historically enabled societies to move through turning points. Instead of developing collective technological competence that builds confidence and social readiness, always-connectedness creates technological dependency without understanding. People become increasingly anxious about technological change because they never develop genuine agency within technological systems—they remain passive users rather than active participants in technological development. This structural disconnection from productive technological engagement prevents the social learning and collective mastery that would enable society to harness information age capabilities for broad-based prosperity rather than elite extraction.

Critically, this passive consumption pattern persists because platform companies face no competitive pressure to develop technologies that enable genuine user agency and creative engagement. Fiscal intervention ensures their survival regardless of social value creation.

Truth vs. Information Abundance: Digital platforms provide unprecedented access to information and enable widespread misinformation and conspiracy theories. Society lacks shared mechanisms for determining truth and building consensus, undermining the social cohesion necessary for collective action. Previous cycles developed shared information institutions through competitive pressure and crisis necessity—newspapers, professional journalism, scientific institutions gained credibility by providing accurate information during crisis periods. Fiscal intervention removes the pressure for information institutions to develop credibility through accuracy, allowing misinformation and propaganda to persist indefinitely.

Political and Social Fragmentation Through Prevented Crisis

Previous technological transitions eventually created new forms of political organization and social solidarity through crisis-driven necessity. The industrial age produced labor unions and progressive reform movements because worker survival required collective action. The railway age enabled national political parties and mass democracy because infrastructure coordination required democratic participation. The automobile age facilitated suburban political organization and consumer advocacy because the Great Depression created conditions demanding collective political response.

The information age, however, has primarily produced political and social fragmentation because prevented crisis eliminates the pressure for collective organization:

Echo Chamber Politics: Social media algorithms optimize for engagement rather than consensus-building, systematically amplifying extreme viewpoints and undermining moderate political discourse. This prevents the social compromise and collective decision-making necessary for institutional adaptation. Previous cycles would have created competitive pressure for media companies to serve genuine democratic needs. Fiscal intervention allows platforms to optimize for profit regardless of democratic consequences.

Eroded Shared Reality: Unlike previous eras where mass media created shared factual frameworks for public debate through competitive credibility pressures, digital media enables completely separate information ecosystems. Different social groups literally inhabit different versions of reality, making democratic governance increasingly difficult. Crisis pressure historically forced information institutions to develop accuracy standards for credibility. Artificial stability removes this pressure.

Weakened Civic Institutions: Digital technologies enable people to opt out of local civic participation while engaging in global online communities. This weakens the local institutions—schools and community organizations—that previous technological transitions strengthened and depended upon for social integration. Previous cycles created survival pressure for local institutions to adapt and provide value. Fiscal intervention allows these institutions to persist without serving genuine community needs.

Identity Politics Over Class Solidarity: Rather than creating new forms of worker solidarity based on shared economic interests, digital technologies enable identity-based political organization that often fragments potential coalitions for institutional change. Crisis pressure historically forced diverse groups to cooperate based on shared economic interests. Artificial stability allows political fragmentation to persist without forcing coalition building around material needs.

The Missing Social Infrastructure and Prevented Development

Most fundamentally, the fifth cycle stalled because prevented crisis eliminated the pressure necessary for developing social infrastructure required for broad-based participation in the knowledge economy. Previous cycles created new social institutions alongside technological infrastructure through crisis-driven necessity:

Public Education Expansion: Industrial revolutions prompted massive expansions of public education because economic survival required educated workers. The information age requires similar investment in lifelong learning systems, but artificial economic stability removes the pressure for educational investment. Instead, fiscal intervention props up obsolete educational institutions while preventing development of information-age learning systems.

Professional Development Systems: Previous cycles created systematic apprenticeship, corporate training, and professional development programs because competitive pressure required skilled workers. The information age demands continuous skill updating, but existing systems remain fragmented and inadequate because fiscal intervention removes the competitive pressure that would force systematic skill development investment.

Social Safety Nets: Previous technological transitions eventually produced unemployment insurance, pensions, and healthcare systems that provided security during economic change through crisis-driven political mobilization. Those safety nets are being reduced and dismantled. The information age requires updated social insurance for technological displacement, but prevented crisis eliminates the political pressure necessary for social infrastructure development.

Community Integration Mechanisms: Previous cycles created new forms of community organization—company towns, suburban neighborhoods, professional associations—that integrated people into the new economic system because survival required social coordination. The information age has produced social isolation and fragmented communities rather than new forms of social solidarity because artificial stability removes the pressure for community innovation.

Why Socioeconomic Readiness Remains Elusive: The Prevented Crisis Dynamic

The Acceleration Problem Amplified by Artificial Stability

Unlike previous cycles that unfolded over decades, allowing gradual social adaptation, digital technologies change at speeds that exceed human institutional capacity. However, the prevented turning point amplifies this acceleration problem by removing the periodic stabilization that characterized previous cycles.

Continuous Disruption Without Clearing: Previous cycles experienced technological acceleration followed by crisis-driven clearing periods that allowed social adaptation and institutional development. The information age experiences continuous disruption without clearing, preventing the stabilization and institutionalization that characterized previous golden ages. Just as society begins adapting to one digital innovation, new technologies disrupt existing arrangements without the periodic crisis pressure that would force systematic adaptation.

Maladaptive Persistence: Artificial stability allows maladaptive institutions and behaviors to persist indefinitely. Previous cycles forced regular elimination of ineffective approaches through competitive pressure and crisis selection. The information age maintains dysfunctional systems through fiscal intervention, preventing the learning process that would enable effective adaptation.

The Scale and Complexity Challenge Without Democratic Pressure

Previous technological revolutions focused on specific domains—transportation, manufacturing, communication—and achieved social integration through crisis-driven democratic participation. The information revolution affects every aspect of human life simultaneously, creating complexity that exceeds social institutional capacity for management and integration, particularly without the democratic pressure that crisis historically provided.

Total Life Integration Without Democratic Control: Unlike automobiles or electricity that enhanced existing activities through democratically shaped development, digital technologies restructured fundamental human relationships according to corporate profit objectives rather than democratic values. Previous cycles forced democratic participation in major infrastructure decisions through crisis pressure. The prevented turning point allows corporate-led total life integration without democratic consent or social input.

Global Coordination Requirements Without Crisis Pressure: Previous cycles could achieve golden ages within national boundaries through crisis-driven domestic institutional development. The information age requires global coordination on issues like data governance, artificial intelligence safety, and digital rights that exceed current institutional capabilities. However, prevented crisis eliminates the pressure for international institutional innovation that global challenges require.

The Democratic Deficit as Prevented Crisis Consequence

Most critically, the information age has proceeded largely without democratic participation or social consent because artificial stability eliminates the crisis pressure that historically forced democratic engagement in technological governance. Unlike previous technological revolutions that involved extensive public debate and democratic decision-making about infrastructure investment and institutional change through crisis necessity, digital transformation has been driven primarily by private technology companies with minimal public accountability because fiscal intervention removes the pressure for democratic control.

Corporate-Led Development: Major digital platforms developed according to corporate profit objectives rather than social needs or democratic values because they never faced the existential pressure that would require social value creation for survival. This creates systematic misalignment between technological capabilities and social requirements. Previous cycles forced corporate adaptation to social needs through competitive and crisis pressure. Prevented crisis allows corporate-led development to proceed indefinitely without social accountability.

Lack of Public Voice: Citizens have minimal influence over digital platform design, algorithmic decision-making, or data use policies that affect their daily lives. This powerlessness generates resistance to technological change rather than engagement with beneficial adaptation. Previous cycles created crisis conditions that forced democratic participation in technological governance. Artificial stability allows technological development to proceed without public input.

Regulatory Capture: When governments attempt technological regulation, technology companies often capture the regulatory process, preventing the institutional innovation necessary for social integration. Previous cycles created crisis pressure that overwhelmed regulatory capture through democratic mobilization. Prevented crisis allows regulatory capture to persist without the social pressure necessary for genuine democratic control.

Breaking the Prevention: Pathways to Cycle Completion

Allowing Natural Clearing Mechanisms

Completing the fifth cycle may require allowing the natural clearing mechanisms that fiscal intervention has prevented:

Controlled Creative Destruction: Rather than preventing all business failures, policy should enable systematic clearing of obsolete institutions while protecting individuals through enhanced social safety nets. This means allowing inefficient companies to fail while providing universal healthcare, education, and income support that enables workers to transition to information-age occupations.

Institutional Sunset Provisions: Educational institutions, regulatory frameworks, and professional associations should face systematic review and potential dissolution if they fail to serve information-age needs. Therefore, this in no way endorses the draconian Austrian School of Economics. Instead, before entering another significant financial crisis, slowly let the air out of the proverbial economic tires. Not doing so creates pressure for adaptation while preventing the indefinite preservation of obsolete institutions.

Platform Accountability: Digital platforms should face existential competitive pressure through antitrust enforcement, data portability requirements, and algorithmic transparency that forces adaptation to genuine social needs rather than pure profit extraction.

Rebuilding Social Learning Systems Through Crisis-Driven Necessity

Completing the fifth cycle requires systematic investment in social learning infrastructure that enables broad-based participation in continuous technological change, but this investment may only be possible through crisis pressure that creates political will for collective action:

Lifelong Learning Systems: Public investment in adult education, community colleges, and continuous skill development programs that provide pathways for technological adaptation across all social groups. Previous cycles created educational expansion through crisis-driven political mobilization. Similar crisis pressure may be necessary for information-age educational investment.

Digital Literacy as Civic Education: Systematic programs that teach not just technological skills but critical thinking about digital media, data privacy, and algorithmic decision-making as essential components of democratic citizenship. This requires crisis-driven recognition that digital literacy is essential for democratic survival.

Community-Based Technology Centers: Local institutions that provide technology access, training, and support while strengthening rather than undermining community bonds and civic participation. These require crisis-driven community organization that artificial stability has prevented.

Reconstructing Social Solidarity Through Shared Crisis Response

The information age golden age requires new forms of social solidarity that bridge digital divides and enable collective action, but this solidarity may only develop through shared crisis experience that artificial stability has prevented:

Universal Basic Services: Public investment in healthcare, education, housing, and internet access that provides security and opportunity for technological participation while strengthening social bonds. Previous cycles created social infrastructure through crisis-driven political mobilization. Similar pressure may be necessary for information-age social infrastructure.

Worker Organization for the Digital Age: New forms of labor organization that address gig economy challenges, provide portable benefits, and enable collective bargaining power in digital labor markets. This requires crisis-driven recognition of shared economic interests that artificial stability has obscured.

Participatory Technology Governance: Democratic institutions that enable public participation in major technological decisions, platform design choices, and algorithmic policy development. This requires crisis pressure that forces democratic engagement with technological governance.

Cultural Integration and Values Alignment Through Crisis-Driven Adaptation

Most fundamentally, social readiness requires cultural work that aligns technological capabilities with human values and social aspirations, but this cultural adaptation may only be possible through crisis pressure that forces value clarification and social choice:

Technology as Public Good: Shifting cultural narrative from technology as private commodity to technology as public infrastructure that should serve democratic values and social needs. This requires crisis-driven recognition that private technological control threatens democratic survival.

Sustainable Digital Culture: Developing social norms about healthy technology use that preserve privacy, community bonds, and mental health while embracing beneficial technological capabilities. This requires crisis-driven awareness of digital technology’s social costs.

Intergenerational Dialogue: Creating mechanisms for productive conversation between digital natives and digital immigrants that builds shared understanding rather than mutual resentment. This requires crisis-driven recognition of generational interdependence.

The fifth cycle’s prevented turning point reveals that artificial stability may be the primary obstacle to information age golden age achievement. Unlike economic factors that can be addressed through policy changes, the prevented crisis dynamic requires either allowing natural clearing mechanisms to operate or creating equivalent pressure through deliberate democratic action. Social readiness may only develop through crisis experience that forces cultural transformation, institutional innovation, and democratic engagement enabling society to collectively shape technological development according to human values and social needs.

Only when artificial stability ends—either through natural crisis and/or deliberate democratic choice—can the information age complete its transition and achieve golden age potential for broad-based prosperity and human flourishing. The prevented turning point suggests that the path forward requires embracing rather than avoiding the creative destruction necessary for technological cycle completion.

Next Chapter Eight: Capital Alignment

Below is the Socioeconomic Readiness listing for the innovations and bibliographies for Disruptions Dawn within the technology cycle library.

Innovation and Bibliography listing Socioeconomic Readiness

The main entrance to Technology Cycles Main Library – The Singularity Stacks Link