Outlining Perez’s Five Technology Cycles

Carlota Perez built a model which shows us that there have been five technology cycles. At the heart of Perez’s theory is a simple idea: every technology cycle revolves around a cluster of new and revolutionized industries. For each cycle in this series, I’ve highlighted the top five or six sectors, though many more industries play supporting roles in the broader ecosystem. We take industrial growth for granted today, but before the Industrial Revolution, only one industry operated at scale: agriculture. Everything else—blacksmithing, carpentry, weaving—remained small-scale and manual. Industrialization, by definition, means “the development of industry on a regional or national scale.”

How Carlota Perez’s Model Works – The Power of Patterns

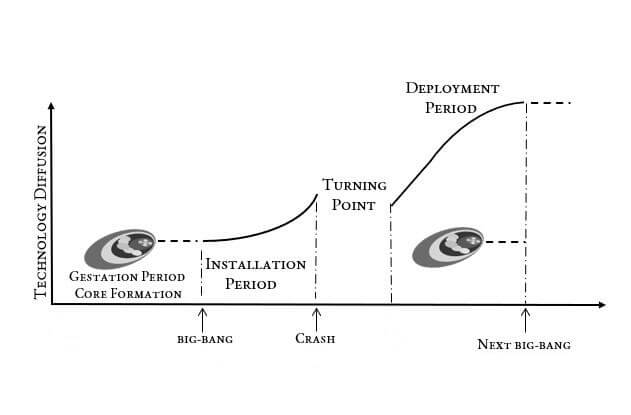

What Perez revealed was remarkable: repetitive cycles in the structural elements of technological development. The history differs, but the dynamics and structure repeat like clockwork. Her theory reveals something profound: every major technological revolution follows a predictable rhythm, much like a symphony played over decades. Steam engines, electricity, automobiles, computers, the internet—each followed the same two-act drama, complete with spectacular crashes, unlikely heroes, and eventual triumph. Perez discovered that every technological revolution moves through two distinct phases, separated by a dramatic turning point that often feels apocalyptic to those experiencing it firsthand.

Gestation Pre-Surge – Core Formation

The gestation period that preceded the Industrial Revolution coalesced into a dense technological core. A core so concentrated that it would serve as the energy to power the Industrial Revolution (technology cycle one). The core formation process unfolded through: initial ripples of unrelated innovations, then early innovations coalescence as inventions responded to bottlenecks created by predecessors, new and revolutionized industries emerged across textiles, power generation, metallurgy, chemicals, and transport, followed by swarming from imitators who improved original designs, and finally the financial reorientation toward industrial ventures. At this juncture, the core was ready for Carlota’s Big Bang moment of Arkwright’s automated cotton mill in Cromford in 1771.

The Cycle Begins – The Installation Period

The first act begins with what Perez calls the “irruption”—the moment when a new technology bursts onto the scene and changes everything. Picture the first steam-powered factories disrupting centuries-old craft traditions, or the first automobiles frightening horses on dirt roads designed for carriages. his Installation Period is characterized by a kind of “Cambrian explosion” of innovation. Entrepreneurs and speculative investors, intoxicated by the technology’s potential, pour money into building the infrastructure needed to support it. Railways spread across continents. Assembly lines revolutionize manufacturing—fiber optic cables snake across the ocean floors. The period is filled with hope and promise.

However, there is a catch: nobody knows how to use these new tools yet. The technology must be “pushed” onto reluctant customers who do not fully understand its benefits. Early adopters often reap significant benefits, but these remain concentrated among a small elite. Speculation runs wild, bubbles form, and eventually, they crash.

The Turning Point

Between the two acts comes a moment of reckoning. The speculative bubble bursts, fortunes are lost, and the technology that once seemed so promising appears to have failed. The collapse of canal mania in 1793, the collapse of railway mania in 1848, and the Great Depression in 1929, following the automobile revolution—each represents this crucial turning point. A worldwide depression demarcates each turning point. In different geographies, they ran for various lengths, but they all began with the same dominoes falling at the outset. But this is not failure—it is transformation. The crash clears away the excess and forces society to figure out how to use the technology productively. It is creative destruction in its purest form.

Turbulence Removed – The Deployment Period

The second act tells a very different story. Now the technology is “pulled” by eager customers who understand its value. The infrastructure built during the Installation Period finally pays off as applications multiply and benefits spread throughout society. Production capital, focused on real economic output, replaces the speculative financial capital of the first phase. This Deployment Period often becomes what Perez calls a “Golden Age”—a time of widespread prosperity, productivity growth, and social progress. Think of the post-war boom that followed the automobile revolution, or the productivity gains that eventually emerged from computer technology.

The Institutional Challenge

But here’s where Perez’s theory becomes truly sophisticated. Technology alone does not create golden ages—institutions do. The rules, regulations, and social norms that govern society must evolve to keep pace with the new technological reality. When they do, the prosperity spreads via positive feedback loops. When they do not, the benefits remain concentrated and the revolution stalls. This “institutional framework” is not just about government policy—it encompasses everything from educational systems to corporate structures to cultural attitudes. Successfully navigating a technological revolution requires re-imagining not just how we work, but how we organize society itself.

The reference library lists the publications and innovations of the five Perezian Technology Cycles. Once complete, nowhere else, anywhere, that will house all of the technology cycle innovations and reference material, which will be housed here. We call our library The Singularity Stacks. The image is a hotlink entrance, as is the hyperlink below.

Relevance today

Because the five technology cycles is so absolutely incredibly misunderstood today – we are stuck in a very uncomfortable situation. Conservatives are doubling down on the way things were in the “golden age” of the prior technology cycle. Instead of how the technology cores are aligned today. Check out this link for the explanation as to how we got here and where and why we are stuck.