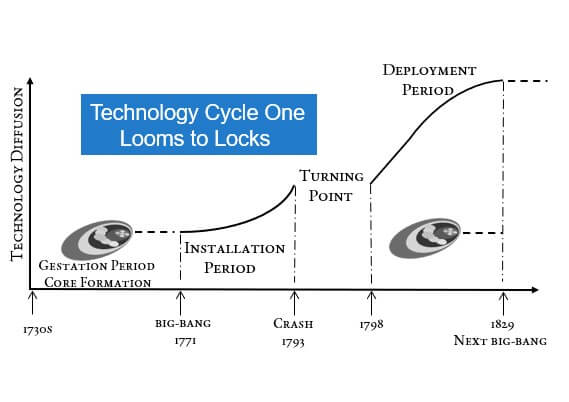

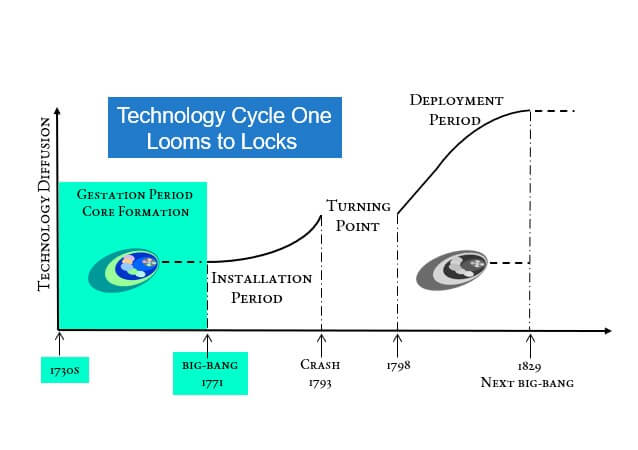

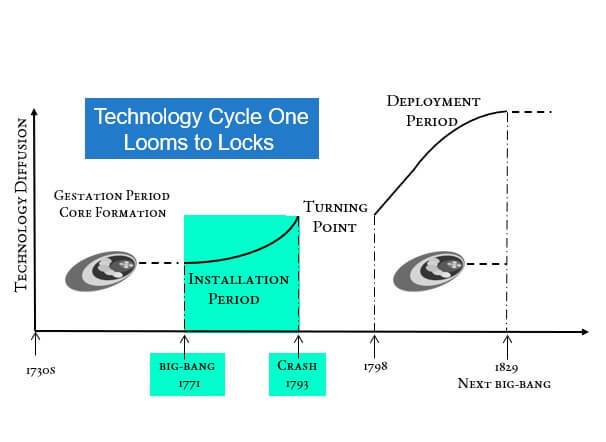

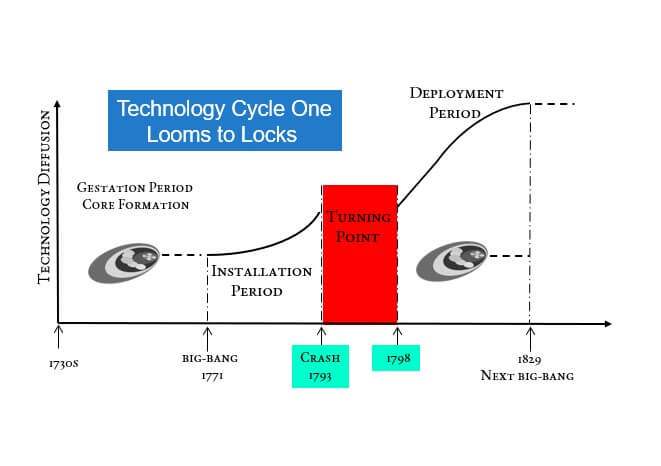

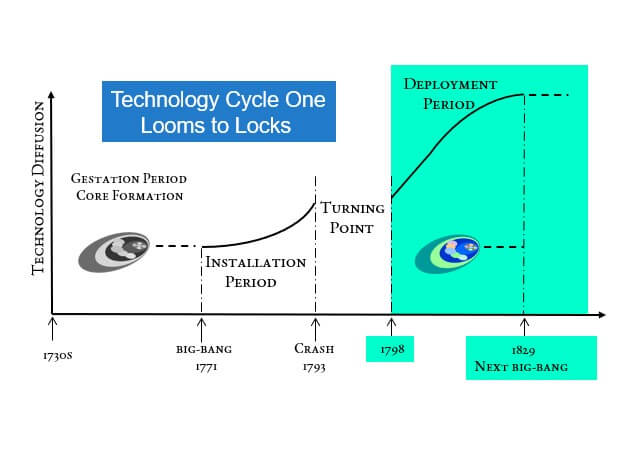

Technology Cycle One: Looms to Locks

The Industrial Revolution: Humanity’s Great Discontinuity

The Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in human history. It changed how people lived, worked, and understood progress. Its speed and scale broke centuries of stability and tradition. Earlier societies evolved slowly, with productivity increasing across generations.

People lived as farmers, craftsmen, or laborers with limited tools. Economic growth was slow, tied to agriculture and muscle power. Technology has advanced so gradually that individuals rarely notice the change. This Malthusian world held humanity within natural energy limits.

The Industrial Revolution shattered those limits with astonishing speed. It began in late-1700s Britain and spread rapidly westward. Steam power and machines created capabilities that never existed before. Humans could now use energy far beyond biological limits. Factories multiplied output, and new industries emerged quickly.

Self-Reinforcing Feedback Loops

Industrial change created feedback loops that drove further change. Improved transport enabled large-scale production and reinvestment in innovation. Each improvement enabled others, compounding growth across industries. Progress became self-sustaining, fast, and far-reaching.

Unlike previous technological advances that remained isolated improvements, industrial innovations created cascading effects that accelerated further innovation. Better transportation enabled more efficient resource distribution, which enabled larger-scale manufacturing, which generated capital for further technological investment, which created new transportation needs, and so forth. This positive feedback loop broke the historical pattern of gradual, linear progress and replaced it with something entirely unprecedented: sustained, compound growth.

Social Transformation

The social implications were equally revolutionary. Old social structures crumbled as people moved to cities. Traditional crafts faded; factories created new types of work. New classes—owners and workers—shaped politics and society. Careers no longer followed family trades, but industrial needs.

Within a few generations, centuries-old social structures crumbled as millions migrated from rural villages to industrial cities. Traditional craft guilds became obsolete overnight. New social classes emerged—industrial capitalists and urban workers—whose relationships and conflicts would define the next two centuries of political development. The very concept of “career” transformed from following predetermined family trades to navigating rapidly evolving industrial opportunities.

The Reinvention of Time

Perhaps most significantly, the Industrial Revolution fundamentally altered humanity’s relationship with time itself. Time itself changed during the Industrial Revolution. Seasons no longer dictated labor—clocks and shifts did. People began expecting progress within their own lifetimes. Industrialization introduced urgency, ambition, and anxiety about the future.

Pre-industrial societies operated on seasonal rhythms and generational timescales. Industrial society introduced clock time, shift work, and the expectation of continuous improvement within individual lifetimes. This temporal acceleration created new forms of human experience: the possibility of dramatic social mobility, the anxiety of technological obsolescence, and the unprecedented prospect that children would inhabit a world radically different from their parents’.

The Industrial Revolution’s significance lies not merely in its material achievements, but in proving that human societies could transcend seemingly permanent limitations through technological innovation. It established the template for modernity itself: the expectation that sustained economic growth, technological progress, and social transformation are not anomalies but normal features of human civilization. This discontinuous leap from millennia of stagnation to exponential growth represents humanity’s great escape from the constraints that had defined our species since the dawn of agriculture.

Below each graphic are the links to go deeper into each of Carlota Perez’s periods which define every technology cycle.

Gestation Period the Core Formation: The Hidden Foundation of Revolution

The Installation Period: Creative Destruction Unleashed (1771-1797)

The Turning Point: When Promise Meets Reality (1793-1797)

For a deeper understanding of the Turning Point.

The Deployment Period: Technology Finds Its Purpose (1798-1829)

The Publications Library for the First Technology Cycle.