Great Technology Surge Cycle – Section Two

Joseph Schumpeter’s work on Business Cycles

Schumpeter’s life work in macroeconomics has placed him in the Pantheon of the most renowned thinkers. Albeit he remains outside of the neoclassical economist canon. Some of his more famous students were John Kenneth Galbraith and Alan Greenspan (Fed Chairman 1987 – 2006). Schumpeter researched technological innovation and business cycles amongst many other topics. He was a prolific thinker, and we touch only on his Long Cycle theories here.

Schumpeter’s theory was not generally accepted in mainstream economics. Some of this was just bad timing. His book Business Cycles was selling very well until Keynes eclipsed it three years later with his own book. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Keynes book quite literally become the text book for macro-economics. Keynesian theory are the tools which all central bankers use to this day to manage market economies.

Monetary Tools

Keynes theory provided the monetary tools for the management of interest rates to balance inflation against unemployment. Those tools all came form Keynes. Though the two disagreed with one another on several major topics, they did respect and even influence one another. Let us now focus purely on the work he did on long cycles.

In the 1930s Schumpeter took up the role of technical progress in the great technology surge cycle. He argued that basic innovations like the steam-engine and the railway came from more than just their invention. Rather it was together with the ‘swarming’1 of smaller, secondary inventions which were the forces that launch a long cycle. In many ways Kondratiev’s work received its greatest expression not by Kondratiev himself, but through Joseph Schumpeter. His book Business Cycles of 1939 is inconceivable without the foundations laid by Kondratiev. Earlier in Schumpeter’s first models there were only two phases: prosperity and depression.

In his monumental book Business Cycles Schumpeter restated and expanded his earlier theory. Later, he concluded that there were four phases in the longer “Kondratieff cycle.” He had embraced Kondratiev work later.2 Schumpeter, like Garvy was working with translated documents. He made the same error Garvy would later. They both had called the cycles with interchangeable names: Long Cycles or Long Waves.

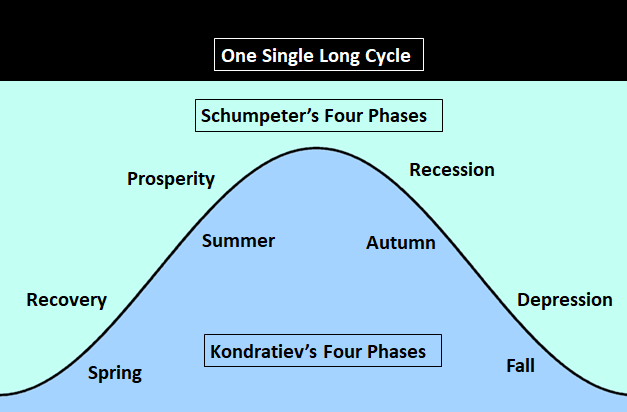

The Great Technology Surge Cycle charts from Schumpeter and Kondratiev

The chart (above left) shows a single cycle featuring both Schumpeter’s and Kondratiev’s labels for the cycle. On the chart (above right) is from Schumpeter’s book Business Cycles page 213. This is the image one encounters most often incorrectly attributed to Kondratiev. Altogether he wrote that the cycles have four phases pretty much along the lines of Kondratiev’s four seasons. Schumpeter went on to describe Long Cycles as “Kondratieff’s” in honor of the Russian economist. Schumpeter decided to call the long cycle ‘Kondratieff waves or cycles’. His work was full of terms such as ‘the Kondratieff depression’, ‘the Kondratieff prosperity’, and ‘the Neomercantilist Kondratieff’. Referring to the entire third great technology surge cycle of steel and technology cores. He also named the sequence of long cycles the first, second, and third Kondratieff’s.3

Where the misrepresentations originated

There was significant maturation of the core technology surges modelling which will continue to be outlined following this paragraph. In order to provide some clarity as to why Long Cycles are not only misunderstood but mislabeled as well. We need to touch on two events. The first error occurs during WW2 when George Garvy, working for N.B.E.R.4, wrote a paper5 reviewing Kondratiev’s theory. Garvy used the now infamous mistranslated 1926 article as his source. Garvy’s paper was widely read in the academic community, including by Schumpeter. The N.B.E.R. had a significant following at that time.

Garvey’s paper was correct in the critical assertion that Kondratiev’s model contained errors as Kondratiev’s dating did not align. Data Garvy had in 1943 showed this. At the end of the 3rd section there is visual further proof for this. However as he was correcting one error he propagated another. Throughout the paper he interchangeably referred to the cycles as long cycles and errantly, long waves. An example to clarify why this distinction is important. Every wave rises and then falls. A long cycle contains two waves and therefore he missed one of Kondratiev’s most salient points. Schumpeter would subsequently also continue propagating this verbiage. He also interchangeably referred to them as either Kondratiev’s or long waves. The theory was overly simplistic back then. The great news is the refinement of the model would continue despite this mistake which still continues to plague us.

Schumpeter builds on Kondratiev

The two major contributions Schumpeter made building on Kondratiev’s work was first in correctly identifying what starts the long cycle. Making a parallel to physics it was in the 1960s that Higgs theory of how mass accumulates in sub-particles. This was critical for understanding how the universe forms. Schumpeter theorized that ‘Kondratieffs’ began as clusters of innovation, swarms that densely packed together to launch the Long Cycle.

These technology “swarms” delivered through step refinement and imitators of the new technologies. They produced the energy to create the core which would launch the new Long Cycle seemingly from nowhere. An example of this was when personal computers (PCs) were first invented by IBM. There were hundreds of companies which made clones of the IBM PCs. Not to mention the other hardware products such as modems, monitors and printers. Schumpeter predicted this with his model for long cycles a half a century before the PC swarming actually occurred.

Swarms

The second thing which Schumpeter correctly theorized was that the technology surge cycles featured “swarms” delivered through step refinement. The imitators of the new technologies unleashed the economic force termed Creative Destruction. Creative Destruction is the process where new innovations replace and obsolete older innovations. Coined by Schumpeter in 1942, he stated that business cycles operate under cycles of innovation. Specifically, markets are disrupted by new innovations. We see this all too clearly today. The Internet killed off printed Newspapers and a radically impacted the retail industry. Retail” brick and mortar stores” struggle against online stores. These are quick examples in Creative Destruction.

A very unusual source

Schumpeter actually got the concept for this from Karl Marx. In The Communist Manifesto of 1848, Marx and Engels described the crisis tendencies of capitalism. They used terms of “the enforced destruction of a mass of productive forces.” Correspondingly within modern economics, creative destruction is one of the central concepts. In Why Nations Fail, Acemoglu and Robinson make the case why creative destruction is beneficial. They argue the major reason countries stagnate and go into decline is due to creative destruction being blocked. Either by ruling elites or monopolies. Creative destruction promotes innovation.

The ensuing postwar Keynesian revolution put Schumpeter’s work on innovation and the business cycle very much into the background. Schumpeter’s work tended to be axiomatic, which means that he worked under the assumption that Long Cycles existed. It would not be until the 1970s that work began to document the assumptions required to prove the theory. He had left some pretty significant questions unanswered, such as why these cycles recur. Nevertheless, his works would remain a rich source of inspiration. Indispensable for anyone who, like Schumpeter, was puzzled by the alternation of phases in prosperity and depression. These have been evident since the Industrial Revolution began.

If you would like to read about Schumpeter’s contributions from his three primary sources, read the next section. To continue exploring the history of technology cycle models, click here—section two—more history of the great technology surge cycles.

Schumpeter’s main contributions

Joseph Schumpeter, the Austrian-American economist, introduced the concept of “swarming” or “clustering” of innovations in his economic theory. He observed that technological innovations tend to appear in clusters or “swarms” rather than in isolation.

Schumpeter argued that when a major innovation emerges, it often triggers a cascade of related innovations and improvements as entrepreneurs rush to capitalize on new opportunities. This clustering effect leads to periods of intense technological development followed by adaptation and economic transformation.

In his work “Business Cycles” (1939), Schumpeter described how these technology swarms contribute to economic cycles and his famous concept of “creative destruction,” where new innovations displace older technologies and business models.

Schumpeter wrote on innovation clustering in “The Theory of Economic Development” (1911 – 1934)—a quick summary.

In “The Theory of Economic Development” (1911/1934), Schumpeter laid the foundational ideas for his concept of innovation clustering, though the full development of his “swarming” theory came later in his work. The key points from this book regarding innovation clustering include:

Entrepreneurial role: Schumpeter emphasized that economic development occurs through “new combinations” (innovations) implemented by entrepreneurs who break established equilibrium.

Non-continuous nature of innovation: He argued that innovations do not appear evenly or randomly distributed over time but tend to emerge in groups or waves.

Economic discontinuity: These clustered innovations create discontinuities in economic development rather than gradual, continuous progress.

Credit and capital: He linked the clustering phenomenon to credit availability, suggesting that financial systems play a role in enabling these waves of innovation.

Early business cycle connection: The book contains his initial thoughts connecting these innovation clusters to business cycles, which he would develop more fully in later works.

While “The Theory of Economic Development” contains these important conceptual seeds, Schumpeter’s more detailed articulation of innovation clustering, or “swarming,” was further developed in his later work, “Business Cycles” (1939), where he more explicitly connected innovation clusters to specific historical periods of economic development.

Schumpeter wrote on innovation clustering in “Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process” (1939)—a quick summary. Second main source.

In “Business Cycles: A Theoretical, Historical, and Statistical Analysis of the Capitalist Process” (1939), Schumpeter significantly expanded his theory of innovation clustering or “swarming.” This work represents his most comprehensive treatment of the topic:

Explicit swarming theory: Schumpeter formally developed the concept that innovations appear in clusters or “swarms,” concentrating at the very start of a technology cycle rather than being evenly distributed over time.

Three-cycle model: He proposed that the economy experiences overlapping cycles of different durations (Kitchin, Juglar, and Kondratieff cycles), with significant innovation clusters driving the longest Kondratieff waves (40-60 years).

Historical evidence: Schumpeter provided a detailed historical analysis, identifying specific innovation clusters tied to particular periods, such as the railroad boom, electrification, and the early automobile era. These are general technology cycles.

Causation mechanism: He argued that once a pioneering entrepreneur successfully introduces an innovation, others quickly follow in “swarms,” creating a concentration of entrepreneurial activity and new business formation.

Wave sequence: Schumpeter described how these innovation clusters create economic waves with distinct phases: initial prosperity as innovations take hold, recession as adjustment occurs, depression during more profound structural changes, and recovery as the economy absorbs the innovations.

Famous for

Creative destruction: He further developed the concept that these swarms of innovation simultaneously create new industries while destroying or transforming existing ones.

Entrepreneurial motivation: Schumpeter explained that the clustering occurs partly because initial innovations reduce uncertainty and create paths for other entrepreneurs to follow.

Schumpeter positioned the emergence of major innovation clusters primarily at the transition from the recovery to the prosperity phase. They were not uniformly distributed throughout the cycle. Innovation clusters were not evenly distributed across all four stages of his model.

He viewed these clusters as the primary initiating cause of new economic upswings. Schumpeter felt that the depressions in every technology cycle marked the start of a new cycle (wave in his words). In his model, the recovery (depression phase) occurred immediately before prosperity, which was the second phase of the cycle.

He worked through the Great Depression, which radically affected his views of the technology cycle and the sustainability of capitalism. Of his four seasons, three of them deal with depression (Recovery, Recession, and Depression). This illustrates the profound impact the Great Depression had on his thinking. This was corrected in Carlota Perez’s “Great Surges of Technology” in 2001.

Schumpeter wrote on innovation clustering in “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” (1942)—a quick summary.

In “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” (1942), Schumpeter’s treatment of innovation clustering is less direct and comprehensive than in “Business Cycles,” as this book focuses more broadly on the sustainability of capitalism. However, it does contain essential elements related to his innovation theories:

Creative destruction elaborated: Schumpeter more fully developed his concept of “creative destruction,” describing how innovation clusters disrupt economic structures by simultaneously creating new industries while obsoleting existing ones.

Innovation as capitalism’s essence: He emphasized that the clustering of innovations and the resulting creative destruction represent the essential fact about capitalism, not price competition or market equilibrium.

Corporate innovation: Unlike his earlier work, which focused on individual entrepreneurs, Schumpeter acknowledged the increasing role of large corporations in generating and implementing innovation clusters.

Sociological impacts: He examined how waves of innovation affect broader social structures and institutions beyond purely economic consequences.

Capitalism’s self-destruction: Schumpeter paradoxically suggested that capitalism’s success in generating innovation clusters would eventually undermine its institutional foundations. Cyclical financial collapses (depressions) are what he was referring to.

Bureaucratization of innovation: He explored how the systematization of R&D in corporate settings might affect the clustering patterns of innovation compared to entrepreneur-driven innovation waves.

Longer term implications

While “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” doesn’t focus specifically on the temporal clustering mechanism of innovations as much as “Business Cycles,” it places the innovation clustering concept within a broader sociopolitical context. It examines its long-term implications for economic systems.

Schumpeter did address how capital formation impacts innovation clusters, and it’s a central element of his theory. In both “The Theory of Economic Development” and “Business Cycles,” he outlined several key relationships between capital formation and innovation clustering:

Credit creation as an enabler: Schumpeter emphasized that innovation clusters require new credit creation. Unlike classical economists, he argued that banks create new purchasing power through credit that enables entrepreneurs to access resources for innovation, rather than merely transferring existing savings.

Capital diversion: He described how innovation clusters form when capital is diverted from established “circular flow” patterns toward new combinations of resources that entrepreneurs implement.

Temporal relationship: Schumpeter positioned capital formation as preceding and enabling innovation clusters, not following them. The availability of credit and capital creates the conditions for swarms of innovations to emerge.

Speculation and investment waves: He noted that successful initial innovations attract further capital, creating investment waves that fund subsequent innovations in the cluster.

Capital

Capital goods industries: Schumpeter particularly emphasized how innovation clusters affect industries producing capital goods, causing these sectors to expand disproportionately during the prosperity phase.

Self-reinforcing cycle: He described a feedback loop in which initial capital formation enables early innovations, whose success then attracts more capital formation, thereby intensifying the clustering effect.

Capital destruction: Interestingly, Schumpeter also analyzed how innovation clusters eventually lead to devaluation of existing capital invested in older technologies, which he viewed as a necessary part of the creative destruction process.

This capital formation mechanism was crucial to Schumpeter’s explanation of why innovations appear in temporal clusters rather than being evenly distributed over time.

Schumpeter points to the early tech cycle as the source of clusters

Schumpeter employed a four-phase concept to describe business cycles, which he sometimes likened to seasons; however, it’s essential to clarify his view on when innovation clusters emerge within these phases.

In Schumpeter’s business cycle theory, particularly as developed in “Business Cycles” (1939), he identified four phases: prosperity, recession, depression, and recovery. Regarding innovation clusters:

Primarily in recovery and early prosperity: Schumpeter positioned the emergence of major innovation clusters primarily at the transition from recovery to prosperity phases. He viewed these clusters as the primary initiating cause of new economic upswings. Schumpeter felt that the depressions in every technology cycle marked the start of a new cycle (wave in his words). In his model, the recovery (depression phase) occurred immediately before prosperity, which was the second phase of the cycle.

He worked through the Great Depression, which had a profound impact on his views of the technology cycle and the sustainability of capitalism. Of his four seasons, three of them deal with depression (Recovery, Recession, and Depression). This illustrates the profound impact the Great Depression had on his thinking. This was corrected in Carlota Perez’s “Great Surges of Technology” cycles in 2001.

Not uniformly distributed: Innovation clusters are not evenly distributed across all four phases. They tend to be concentrated at specific points in the cycle rather than appearing consistently throughout.

Secondary Innovations

While breakthrough innovations cluster near the beginning of upswings, Schumpeter acknowledged that secondary, adaptive innovations might appear throughout other phases as the economy adjusts.

Recession and depression as adjustment periods: Schumpeter viewed these phases not as times of major innovation clustering, but as necessary periods of economic adjustment to the disruptions caused by earlier innovation waves.

So while Schumpeter’s business cycle had four phases, he did not view innovation clusters as equally prevalent in all four “seasons.” Instead, he saw them as particularly concentrated in specific phases (primarily recovery/early prosperity), serving as the trigger for the cycle itself rather than a consistent feature throughout all stages. Schumpeter was incorrect with his timing in his models. Carlota Perez in 2015 said, “‘overcoming some of the weaknesses in Schumpeter’s pioneering formulation as being ‘the best tribute to the spirit of his work.’”

Capital Formation

Schumpeter’s analysis of when capital formation occurs within innovation clusters is nuanced and involves several phases. While he didn’t present a simple linear sequence, his work (particularly in “Business Cycles” and “The Theory of Economic Development”) suggests a specific pattern:

Initial capital formation precedes the cluster: Schumpeter emphasized that the earliest stage involves credit creation and capital formation that enables pioneer entrepreneurs to implement breakthrough innovations. This initial capital formation is a prerequisite for the cluster to begin.

Accelerating capital formation during early cluster growth: Once the first successful innovations demonstrate viability, Schumpeter described a rapid acceleration of capital formation as more entrepreneurs enter and investors seek to capitalize on the emerging opportunities. This represents the most intense period of capital formation.

Speculative capital formation mid-cluster: As the innovation cluster gains momentum, Schumpeter noted that capital formation often becomes increasingly speculative, sometimes exceeding what’s required for the actual innovations themselves.

Capital reorganization late in the cluster: Toward the later stages of an innovation cluster, Schumpeter observed that capital formation shifts toward consolidation, rationalization, and efficiency improvements rather than revolutionary new implementations.

Capital destruction concurrent with new formation: Importantly, Schumpeter stressed that throughout the cluster’s development, capital formation is co-occurring with capital destruction (as innovations render existing capital stock obsolete).

Schumpeter viewed the relationship between capital formation and innovation clusters as dynamic rather than strictly sequential. While initial capital formation enables the cluster to begin, the subsequent swarm of innovations drives further waves of capital formation, creating a mutually reinforcing process that continues until the cluster’s innovative potential is largely exhausted.

General pattern inferred

Schumpeter addressed the sequence of clustering or swarming in technological innovation, although not with the same level of detail as his broader theory. In his analysis, it can be inferred that he identified a general pattern to innovation swarming:

Initial breakthrough innovation: A major technological or economic innovation creates new possibilities.

Primary wave: Entrepreneurs immediately recognize and exploit the direct applications of the innovation.

Secondary waves: As the innovation proves successful, more entrepreneurs enter with refinements, improvements, and related innovations.

Diffusion and adaptation: The innovation spreads across different industries and sectors, often in modified forms.

Maturity and standardization: Eventually, the pace of innovation in that cluster slows as the technology matures.

Schumpeter noted that these sequences weren’t strictly linear and could overlap. He was particularly interested in how these innovation clusters related to business cycles and economic development, focusing more on the financial consequences of swarming rather than creating a detailed taxonomy of the sequence itself.

His work was later expanded by other economists and innovation theorists who developed more structured models of innovation diffusion patterns.

The numbered sequence isn’t directly attributable to Schumpeter in that specific structured format. Schumpeter discussed the clustering or swarming of innovations in his works, particularly in “Business Cycles” (1939) and “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy” (1942). Still, he didn’t explicitly outline the sequential pattern I described in my previous response with those specific numbered steps.

The structured sequence listed is more of a synthesis and interpretation of Schumpeter’s broader ideas by later scholars and economists who built upon his work. Schumpeter’s original contribution was identifying that innovations tend to cluster together temporally rather than appearing randomly throughout time, which he linked to business cycles.

Continuing on with the history of the great technology surge cycles. Click here—for section three

The Great Technology Surge Cycle – Section Two – Footnotes Follow

- Hansen, A. 1951. “Schumpeter‟s Contribution to Business Cycle Theory‟ The Review of Economics and Statistics ↩︎

- Long Wave Theory. Elgar Publishing 1996. Volume 69, The International library of critical writings in economics. Edited by Christopher Freeman. Page 299 Cycle Theory‟ The Review of Economics and Statistics ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development. Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. By Vincent Barnett. Publisher Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Page 136. ↩︎

- The National Bureau of Economic Research still exists today: nber.org/ ↩︎

- Kondratieff’s Theory of Long Cycles. Article by George Garvy. The Review of Economics and Statistics. MIT Press, Vol. 25 No. 4 (Nov., 1943), pp. 203-220 ↩︎