Great Technology Surge Cycle – Section Three

Advances in technology cycle theory modeling

The 1970s

In the 1970s Schumpeterian economics were revived as a potential post-Keynesian alternative to neoclassical economics. The neoclassical canon did not even consider innovation, entrepreneurship, and unbalanced growth. The feel of economic stagnation starting in the 1970s served as the fuel for Schumpeter’s revival. The drumbeat of the dreary daily news showing the closures in steel mills and auto plants. Along with the rising tide in unemployment was something which was palpable. It wasn’t theory. It was visceral. The major role technological change plays in generating economic growth spurred academia. The reasons for the revival was due to the increasing realization innovation cycles.

He saw the economic process as part of the larger social and historical frame of reference. Schumpeter had a complex vision of economic processes. Neoclassical macroeconomics had never attempted to address these processes.1 Some economists had taken up looking at the Long Cycles again. This did not mean they produced great scholarship right out of the gate.

Gerhard Mensch was a German economist as a disciple of Schumpeter who worked on innovation research. He stated that Schumpeter’s swarms of technology were imitators who in jumping on the “bandwagon.” That these imitators of the technology cores pushed the cycles forward. The problem was Mensch was looking at the wrong swarms. The technology innovations Mensch referenced turned out to be unrelated. Chris Freeman working at the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) in 1983 said he couldn’t find the bandwagon effect. At least not where Mensch had said they are located (in depressions). It was Mensch who made an early attempt at revival.2

Mensch would stimulate thinking and that was key at that time to get the cycle research moving again.

The French regulation school3

Next up were the members of the French Regulation School. The crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression was the reason why regulations were put in place. The 1933 Glass Steagall Act effectively separated commercial banking from investment banking. It also created the Federal Deposit Insurance (FDIC) at the same time. The Regulation school was working in France where the economic instability and stagflation had ran rampant in the 1970s. France was not unique as this was the case in most industrialized nations. The Regulation school sought to apply systems theory to economics in order to bring regulations to address stagflation. Such as the kinds passed in wake of the Great Depression to address the economic woes of the 1930s.

Unwinding The Great Depression regulations

Most of the West, however, would move in the polar opposite direction. Later in the 1980s, the Reagan administration began to erode the Glass-Steagall Act under a political construct pushing for deregulation. That plan also failed in the USA, as well as under Thatcher in the UK. The removal of Glass-Steagall and other banking deregulations was the direct cause of the 2009 banking crash. Commercial banks had become investment houses, creating new, toxic financial products such as derivatives. Derivatives enabled investment houses and banks to increase their leverage to a jaw-dropping ratio of 40 to 1. For every real dollar on hand in the banks, their bets were 40 times greater. This meant they were not even close to liquid and could not cover what they owed as the market collapsed. Governments worldwide were compelled to intervene and inject capital to stabilize the markets.

The needs for cycle insights

This short history of why wanton deregulation was an awful idea is to underscore the criticality in understanding technology cycles. That is without mentioning the additional debt burdens ladled on to Western economies. The result of cash injections and liquidity required to keep the economies afloat. Finally the School’s research would influence other economists who were working to evolve Long Cycle theory.

Impacting neoclassical economics

Evolutionary economics began to gain traction in academia. Innovation and technology had hardly been even mentioned in classical macroeconomic textbooks. Measurements such as GDP were only adopted as an official measurement for the first time in 1944.4 The US embraced GDP to measure bomb and bullet production at the end of WW2. It will take quite some time to change the ingrained neoclassical model of macroeconomics.

Variables value and placement matter

In reading several histories of this period I summarize them as follows. They looked at the wrong time frames to scientifically. They did this to try and prove the existence of these economic cycles. Some simply used the wrong model/template. An example for this was the MIT Systems Dynamic National Model. MIT attempted to unfold the progression of policies and structure as the cause for the national economy within their model. They described the cause of depressions were due to the capital plants as being over built and therefore worn out. Pretty well known today that the crashes in reality come from the formation of overvalued investment bubbles. These form due to over investment and not the economy “wearing out.”5

As you would suspect from MIT – their math was correct. The assigned variables were wrong because they were using the wrong dates to model. But they were now taking economic, mathematical and scientific approaches to techno-economic paradigms which had never been done before. The basic academic blocks had to be recorded first. This began in the 1970s with the documentation in the causes for the economic factors. These were shown to be the effects for the cycles recurrences.

Evolutionary economics takes a fresh look

One of the central tenants in evolutionary economics approaches of looking at all sources. These even included Marxists. They picked out the good bits and simply discarded the bad ones. The old approach was in tossing out 100% of any thinking judged to have been circumspect. I would like to mention that I read several Marxist historians such as Eric Hobsbawm and Tony Judt. I read almost everything they published because at the very least they addressed economic drivers and history. They did this when almost no other historians had taken that approach.

When I undertook documenting technology cycles, I found that almost every economic source I read quoted historians like Hobsbawm. The economic interpretation of history is what the common thread is. To be very clear I do not endorse communism as it is based on an enormous philosophical error by Marx. In the table at the top is a link which explains Marx’s mistake.

Christopher Freeman brings the great technology surge cycle into academic economic studies

Freeman was recognized as one of the founders of the post-war school of Innovation Studies. He was the founder and the first Director, from 1966 to 1982 for a new unit. The Science Policy Research Unit of the University of Sussex, England. Freeman as the founder and first Director of SPRU is an uncanny historical parallel. Kondratiev founded the Conjecture Institute 40 years earlier. They both did so to study what was considered to be academically out of bounds.

Freeman made pioneering contributions to innovation studies in a number of respects. First he helped to shape a tradition of research into firm-based innovation during the early 1970s. Secondly the research yielded from his book The Economics of Innovation. This at a time when academically macro-economics did not study innovation at all. Third he influenced international trade through a series of commissions from governments to advise them on innovation policies. His reflections were informed on the notions put forward by the two economists with interpretations of Marx’s ideas on capitalism. The economists were the Russian Nikolai Kondratiev and the Austrian American Josef Schumpeter.

Freeman’s contributions

Freeman and SPRU, played an essential role in recognizing the historic significance of the emergence of microelectronic based technologies. This matured into the development of what has come to be called the Techno-Economic Paradigm theory in Long Cycles. He co-authored As Time Goes By in 2001 with Francisco Louçã.6

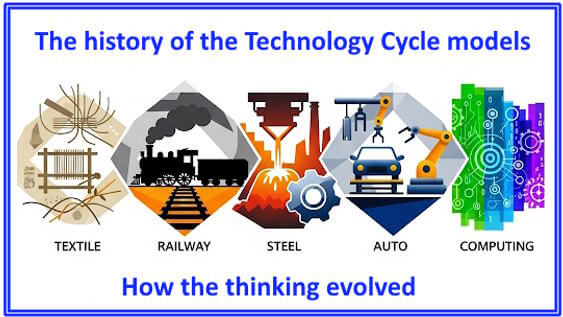

In it the authors put the Internet revolution in the perspective of the four prior cycles in technical change. Steam-powered mechanization, electrification, and motorization (internal combustion engine). The book argues for a theory of reasoned economic history which assigns a central place to these successive technological revolutions.

As Time Goes By is where my reading intersected with what was the latest cycle theory thinking. He would also collaborate with Carlota Perez. She went on to became the titan of the Techno-Economic Paradigm for innovation cycles. Carlota’s insights in how innovation periods and phases integrated to continually power the repetitive cycle. Freeman however, brought innovation into academic macroeconomics as a discipline. One can’t underscore how import Freeman’s work was at every level.

Christopher Freeman’s Critical Collaboration

Let’s move onto section four of the evolution in technology cycle theory. To see where the current thinking now is. In section four we introduce the remarkable economist Carlota Perez. Carlota delivers on Box’s maxim. A model that is very useful for the great technology surge cycle.

The Great Technology Surge Cycle – Section Two – Footnotes Follow

- Technology and the Human Prospect. Published by Frances Pinter Ltd, England 1986 Edited by Roy M. MacLeod. Page 197. ↩︎

- Long Wave Theory. Elgar Publishing 1996. Volume 69, The International library of critical writings in economics. Edited by Christopher Freeman. Pages 133 – 134. ↩︎

- Members of the Regulation School: Alain Lipietz, Jacques Mistral, Robert Boyer, and Michel Aglietta ↩︎

- The Bretton Woods conference in 1944 ↩︎

- Long Wave Theory. Elgar Publishing 1996. Volume 69, The International library of critical writings in economics. Edited by Christopher Freeman. Pages 313 – 320. ↩︎

- As Time Goes By. Oxford University Press. From the Industrial Revolutions to the Information Revolution. By Chris Freeman and Francisco Louçã. 2001 ↩︎