Nikolai Kondratiev’s Theory and Impacts

Kondratiev’s Theory, Influences & Impacts

Few people have read Kondratiev’s theories—and for good reason. He wrote in Russian, and when he met with economists in Europe and the U.S., they urged him to publish in English or German. At the time, few people spoke Russian, and even fewer could read it. His life was tragically short. He did most of his research during the 1920s. The Soviet authorities jailed him in the 1930s and executed him in 1938.

Kondratiev carried out his research within the early Soviet Union. The mere fact that he managed to develop Long Cycle theory in such an environment is remarkable. Despite the significance of his ideas, only one heavily abridged article—published in German in 1926—reached international audiences during his lifetime.

He first introduced the concept of Long Cycles in his 1922 monograph The World Economy and its Conjuncture During and After the War. He published his first dedicated paper on Long Cycles in Questions of Conjuncture in 1925. The Review of Economic Statistics published a translated version of this paper in 1935. On February 6, 1926, he expanded and revised his work at the Institute of Economics in Moscow.

In 1928, Kondratiev published what many consider his most important work on Long Cycles. A detailed analysis of the relationship between agricultural and industrial prices. This paper marked his final contribution to the subject. As a result, he only published work on Long Cycles in 1922, 1925, 1926, and 1928. His contributions, though limited in number, were profound.

Popular Beliefs

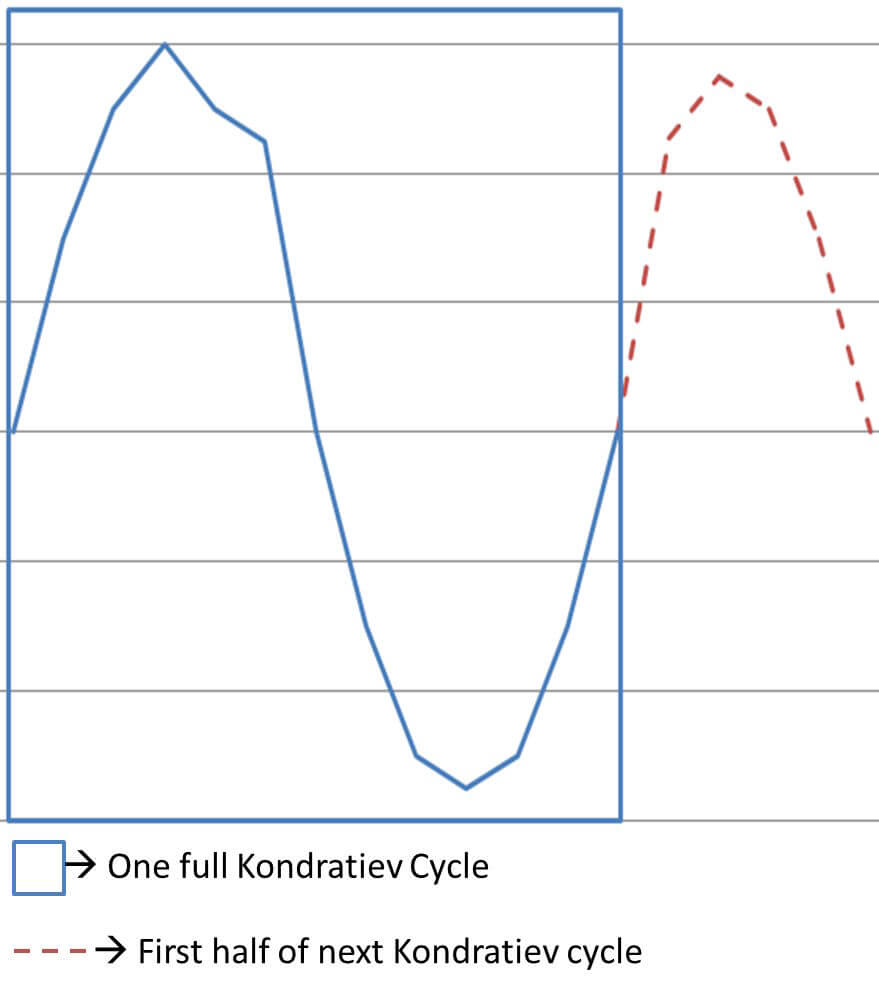

Contrary to popular belief, Kondratiev never used the term “long waves.” He deliberately chose “cycle” over “wave” because he believed a “wave” represented only half of a cycle. Either the rising (povyshatel’naya volna) or declining (ponizhatel’naya volna) phase. He consistently portrayed this distinction in his writing.1

We place the first Kondratiev cycle between the 1780s and 1842. The second unfolds during what historians call the age of steam and steel, spanning from 1842 to 1897. The third, driven by electricity, chemistry, and motors, begins in 1898.2 At this point, we must establish a baseline: Kondratiev’s model ultimately failed. History invalidated his specific framework. After hitting a low in the early 1930s, price levels in every major industrial country rose almost without interruption. This prolonged upswing broke the wave-like pattern Kondratiev had identified from 1780 to 1920. Both exceeded the duration and magnitude of previous cycles. An extended upswing disrupted the regular cyclical movement in price levels that Kondratiev had identified from 1780 to 1920. It lasted longer than both phases of earlier cycles and pushed prices far beyond their previously observed limits.3

Search Results

Search results for terms like “long waves” or “Kondratiev cycles” fascinate me. They almost always display numerous graphs claiming to represent Kondratiev’s work—yet none of them do. That’s because Kondratiev created only one graph illustrating a long cycle, and almost no one has ever seen it. I had to travel to the Lippincott Library at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton Business School to view it myself. That library holds what even the Library of Congress does not. T the complete four-volume set of Kondratiev’s collected works, published in 1998. On page 173 of Volume One, I found the only graph he ever drew of long cycles. It depicts one and a half cycles—and looks like the image shown below.

The graph comes from a short chapter that mostly lists revolutions and wars. Kondratiev associated those events with the upswings of each cycle. The editors included the graph near the end of this list, but Kondratiev never fully explained why Long Cycles exist or what causes them to repeat. Why, then, did he risk his life to develop this theory without stating its purpose?

No Time

The answer is simple: he ran out of time. Only after his imprisonment and as his health failed did he begin outlining brief reflections on these topics. He addressed them for the first time in Suzdal prison. He had time to reflect after a decade of relentless data collection. During the 1920s, he compiled and analyzed trends in prices, wages, and other economic indicators. He hoped, hoping to guide Russia’s transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy.

His ideas for the first Five-Year Plan emphasized investing in agricultural infrastructure so farmers could retain more profit and drive economic growth. Upon returning from a research trip to the United States, he praised the entrepreneurial nature of American farmers and their effective use of capital. He believed that if Russian farmers received similar support, they could organically trigger industrial development.

Despite working in the heart of a totalitarian regime, Kondratiev wasn’t a committed communist. He resembled today’s macroeconomic pragmatists more than a Marxist ideologue. As a young man, Tsarist authorities twice arrested him for promoting democratic ideals. He later criticized the Bolsheviks after they dissolved the democratically elected Duma, where he had been working.

Studied the West

Kondratiev encountered the concept of Long Cycles while studying Western economies. He worked under a regime hostile to capitalism, yet when Soviet officials asked him to forecast capitalism’s end, he refused—because he didn’t believe capitalism would collapse. His refusal, along with his unorthodox thinking, ultimately led to his demise.

In his 1926 article, he remained loyal to his theory while cautiously navigating Soviet political dangers. He wrote:

“Critics have argued that Long Cycles result from random external factors like changes in technology, wars, the incorporation of new regions into the world economy, or fluctuations in gold production. These factors matter—but they confuse causes with consequences.”

And later:

“In asserting the existence of Long Cycles and denying they result from random events, we argue they stem from causes inherent to the capitalist economy… Though we do not intend to build a complete theory, our view is clear.”4

USSR Pressures

The Soviet regime forced Kondratiev to equivocate, as he worked at the heart of the fledgling USSR, where authorities enforced economic orthodoxy at gunpoint. Vincent Barnett, Kondratiev’s most thorough biographer, captures this tension in Kondratiev’s own words. “Technology stimulates upswing through invention.”5 Barnett also observed, “While World War II fits the Long Cycle’s international pattern, it’s likely the last thing Kondratiev would have expected after two decades of economic downswing.”6

The last major reason why Kondratiev never really postulated why the cycles repeat is because he had only lived when two and half cycles had occurred. Further he utilized dates supplied by others investigating the Long Cycles existence. He did compare prices, wages and the like against those dates therefore he knew a model was in all of that data. He just never had the time to pull it together. This is one of the primary reasons I have spent the time to document all of this.

The reality is that very few people have ever read what Kondratiev thought or truly understand the barest outlines of his long cycles. No what you find is people filling in a general model with their own thoughts and typically without the research which Kondratiev actually dedicated his life in pursuit of. The payoff will come later with economists who have the data and time to hammer out a functional long cycle model.

Kondratiev’s Incomplete Theory and Its Structure

From his later, unpublished writings, we can infer a few key ideas:7

- The timing of “extra-economic” events during the Long Cycle.

- The cycle’s own rhythm or periodicity.

- The feedback loops within the cycle, suggesting an emerging endogenous theory.

In truth, Kondratiev had too little data and time to build a comprehensive model. He documented the dates of upswings and downswings, which he attributed to the rising and falling waves within each Long Cycle. He based his logic on four pillars, one of which—gold mining as a money supply driver—has since become obsolete with the end of the gold standard.

However, three pillars have proven timeless:

- Technical innovation – He wrote about how major inventions precede changes in manufacturing techniques and capacities. Today, we see this in digital innovations like cloud computing, virtualization, and AI.8

- Leading national economies – He believed the expansion of certain leading nations’ economies powered global cycles. For example, the U.S. played a central role during his time.9

- Social upheaval – Kondratiev believed civil and global wars consistently accompanied the Long Cycle’s peaks and troughs. While he misjudged the timing, later economists recognized social unrest as a structural component of the cycle.

The social upheavals repeat in every long cycle. The upheavals from civil wars and wars between nations are one of the issues that continue to generate the ongoing interest in Long Cycle theory. Kondratiev tried to fit social upheavals into specific up and down swings. His timings were incorrect as Long Cycle theory had not yet matured for accurate recording. BUT. Later, Long Cycle economists recognized that social upheavals are and have been a structural element in long cycles. However, timing wars are not predictable in long cycles. The social upheavals are however. Much – much, more on this later.

Why no framework?

Why didn’t Kondratiev ever produce a framework based on all the research and data? You can’t forget he was working inside of the infant USSR. So early, Lenin was still alive when Kondratiev began pursuing Long Cycles. The early USSR was predicated primarily on the Bolshevik reading of Karl Marx’s tome Das Kapital. In Das Kapital Marx employed an unsophisticated version of the theory for the ‘life period of capital goods’ to explain business cycles.10 I suspect that Kondratiev in both breaking new ground while working with the kryptonite of capitalism, was trying to link his work to Marx’s Kapital. He desperately tried to remain squarely within the macroeconomic neo-classicist canon. In classical economics, capital goods depreciate over time, and the replacements of these goods help fuel the economy.

Kondratiev’s Central Theory of Long Cycles

Kondratiev’s Long Cycle theory focused on two key ideas:

- The discontinuous replacement of basic capital goods

- The periodic nature of capital investment

He believed that Long Cycles stemmed from spurts in capital goods investment—railways, canals, factories, infrastructure—that did not occur continuously but in bursts. These bursts aligned with economic upswings. Today, we recognize that modernization, rather than wear-and-tear, drives the second half of each Long Cycle.11

Kondratiev’s Influence

Almost immediately after it was proposed, the Kondratiev cycle achieved a certain infamy among both Soviet and Western economists. It is probably true to say that much of the attention was negative, in that many economists were unconvinced that any such cycle exists. For Soviet critics the idea of Long Cycles went counter to the desire for a final and decisive collapse of capitalism; for many Western critics there was insufficient evidence to support Kondratiev’s hypothesis. Some Western economists incorrectly assumed that because the idea of long cycles emanated from the USSR, it must be Marxist in spirit, and criticized it and its originator on this basis.

However, a few Western economists took up the long cycle torch with enthusiasm, most notably Joseph Schumpeter, Walt Rostow, and Ernest Mandel. Rostow is known for his book The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Rostow’s theories were embraced by both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations (serving as national security adviser to the president). Mandel was famous for having correctly predicted at the beginning of the 1960s, as Milton Friedman (Nobel laureate economics 1976) had, that the postwar economic boom would end at the close of the decade.

Schumpeter

Schumpeter’s two-volume Business Cycles of 1939 remain one of the all-time great accounts of economic fluctuations, and was heavily dependent on his own interpretation of the long cycle idea. Schumpeter decided to call the Long Cycle the ‘Kondratiev cycle’, and his work was full of terms such as ‘the Kondratiev depression’, ‘the Kondratiev prosperity’, and ‘the Neomercantilist Kondratiev’. He also named the sequence of Long Cycles the first, second, and third Kondratiev. In his use of the idea of interrelating cycles of various periods Schumpeter was following Kondratiev’s footsteps in methodology as well as in concrete specifics.12

Kondratiev’s Contributions

To conflate Kondratiev’s contribution to economics simply with the idea of Long Cycles is missing the point entirely. Together with others like Wesley Mitchell, Kondratiev pioneered a fundamentally new approach to the study of economic conjuncture Long Cycles actually exist or not has little bearing on the importance juncture within which the Long Cycle was only a small part. Whether Long Cycles actually exist or not has little bearing on the importance of this approach. Kondratiev attempted to integrate the study of various lengths and amplitudes of cycle, and to analyze movements in particular sectors and elements of the economy as parts of a conjectural whole.

This approach was most clearly seen in Kondratiev’s 1928 paper on the relative dynamics of industrial and agricultural prices, this being whole. This approach was most clearly seen in Kondratiev’s 1928 paper on the relative dynamics of industrial and agricultural process, this being why it was presented in detail. Kondratiev thus strived to further develop statics and dynamics in economics, a distinction (gap) which had existed in the neoclassical economics for many decades. While Kondratiev was certainly not the only economist moving in this direction in the 1920s, he deserves to stand alongside the other currently more famous pioneers. Schumpeter was published in his day and therefore famous for his work based Kondratiev. It is only due to the publication of the complete Kondratiev’s works in the 1990s which enabled a view into just how far reaching his thinking actually was.

Conjecture Integration

Finally, Kondratiev’s work on conjuncture also attempted the integration of economic theory with economic policy, in that the theory of conjuncture was to be used to provide policy guidance in composing economic plans and in setting economic variables such as tax levels. Kondratiev may have been less successful in realizing this goal in the concrete conditions of the USSR in the 1920s, but the general approach remains impressive.

As regards its policy relevance today it should be noted that at a dinner hosted by the German Federation of Industry in 1996, the German president Mr. Herzog raised the prospect that Germany might miss out on the fifth long cycle based on informational technology. Noting that Germany had been a technological pioneer in the second, third, and fourth long cycles, Herzog stressed the importance of investing in R&D to ensure that Germany played a full role in the fifth Kondratiev cycle. The Kondratiev cycle thus still remains in popular consciousness as far as economic policy-making is concerned.13

We will revisit this topic with Long Cycles being subsumed within the evolutionary economics paradigm. Evolutionary economics specifically utilizes dynamic measurements for planning on greener economies and other dynamic measurement problems which neoclassical economics does not address. Long cycles will occupy a place within evolutionary economics due to functionality as a useful contextual planning and measurements tool.

Kondratiev Influences

Joseph Schumpeter

In the 1930s Schumpeter took up the role of technical progress in long cycles, and argued that basic innovations like the steam-engine and the railway (together with the ‘swarming’ of smaller, secondary inventions) could launch a long cycle. In many ways Kondratiev’s work received its greatest expression not by Kondratiev himself, but by Joseph Schumpeter, whose Business Cycles of 1939 is inconceivable without the foundations laid by Kondratiev.

Schumpeter wrote:

… if innovations are at the root of cyclical fluctuations, these cannot be expected to form a single wavelike movement, because the periods of gestation and of absorption of effects by the economic system will not be equal. There will be innovations of relatively long span, and along with them others will be undertaken which run their course, on the back of the wave created by the former, in shorter periods. This at once suggests both multiplicity of fluctuations and the kind of interference between them which we are to expect.

Schumpeter Business Cycles

In his two-volume study Business Cycles, Schumpeter acknowledged that economists before Kondratiev had noted elements of the long cycle, but proclaimed that:

“It was N.D. Kondratieff, however, who brought the phenomenon fully before the scientific community and who systematically analyzed all the material available to him on the assumption of the presence of a long wave, characteristic of the capitalist process.”14

Schumpeter’s two-volume Business Cycles of 1939 remain one of the all-time great accounts of economic fluctuations, and was heavily dependent on his own interpretation of the long cycle idea. Schumpeter decided to call the long cycle the ‘Kondratiev cycle’, and his work was full of terms such as ‘the Kondratiev depression’, ‘the Kondratiev prosperity’, and ‘the Neomercantilist Kondratiev’. He also named the sequence of long cycles the first, second, and third Kondratiev.15

In The Growth and Fluctuation of the British Economy Schumpeter’s use of Kondratiev’s work was analyzed in detail and Kondratiev was given credit for certain specific propositions. For example the tendency for prices to rise during the period when technical innovations were being introduced, but before they yielded lower costs and increased output, was called ‘the Kondratiev factor’.

ROSTOW 1960s

Rostow’s work in the 1950s on the process and stages of economic growth was also greatly influenced by Kondratiev’s approach to analyzing long-term change. In a letter to the author (Vincent Barnett) Rostow admitted that he knew of Kondratiev’s work early on in his career, and linked his knowledge of Long Cycles with his work on long-term UK data series which eventually formed part of the two-volume study The Growth and Fluctuation of the British Economy, 1790-1850.

In this letter Rostow outlined that two elements of Kondratiev’s work in particular were puzzling to him. Firstly, that Kondratiev did not have a theory of Long Cycles, and secondly whether wars could be related to Long Cycles. Rostow tested the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, Bismarck’s wars, and the First World War for correspondence with the Long Cycle, but he found that only the American Civil War was connected. Thus Kondratiev’s long cycle hypothesis had an influence on Rostow’s work on the British economy.16

Long Run Dynamics Impacts

Kondratiev’s work on long-run dynamics also stimulated later work in indirectly related areas. For example W.W. Rostow’s books on economic growth are Kondratievian in various respects. Rostow emphasized how not only the rate and direction of economic growth, but also the sequence of development was crucial to success. Kondratiev’s trip to the USA allowed him to see this aspect of the problem clearly, although he did not integrate it into a complete theory as Rostow later would.

Although in 1990 Rostow would write of a possible ‘requiem for Kondratiev cycles’, caused by the forces making for long cycles in relative prices disappearing, the fact that he was still using Kondratiev’s framework sixty five years after the first paper on long cycles was published says much about Kondratiev’s importance. Rostow went on to become an advisor on foreign affairs in the Kennedy administration and to write two further classics in growth theory, The Process of Economic Growth of 1952 and The Stages of Economic Growth of 1960.

The Footnotes Follow

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Page xxxvi. ↩︎

- IBID Page xliv. ↩︎

- Business Cycles and Depressions. Edited by David Glasner. Garland Publishing 1997. Page 365. ↩︎

- IBID Pages lxxi-ii. ↩︎

- IBID Page lxxii. ↩︎

- IBID Page lxxviii. ↩︎

- BID Page lxxii. ↩︎

- IBID Page lxxii. ↩︎

- IBID Page lxxiii. ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development. Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. By Vincent Barnett. Publisher Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Page128. ↩︎

- The Works of Nikolai D Kondratiev (The Pickering Masters). Basic problems of Economic Statistics and Dynamics. Volume 1. Nikolai D. Kondratiev (Author), Edited by Natalia Makasheva, Warren J. Samuels and Vincent Barnett. Translated by Stephen S. Wilson. Publisher: Routledge (1998). Pages 128-129. ↩︎

- Kondratiev and the Dynamics of Economic Development. Long Cycles and Industrial Growth in Historical Context. By Vincent Barnett. Publisher Palgrave Macmillan; 1998. Page 136. ↩︎

- IBID Pages 140-141. ↩︎

- IBID Page 6. ↩︎

- IBID Page 136. ↩︎